Kamil Dunkowski, an expert watch refinisher and restorer based in Poland, is obsessed with zaratsu polishing. “For me, zaratsu is all about reflection of the light,” he told me. “I believe zaratsu polishing is the identity of Grand Seiko.”

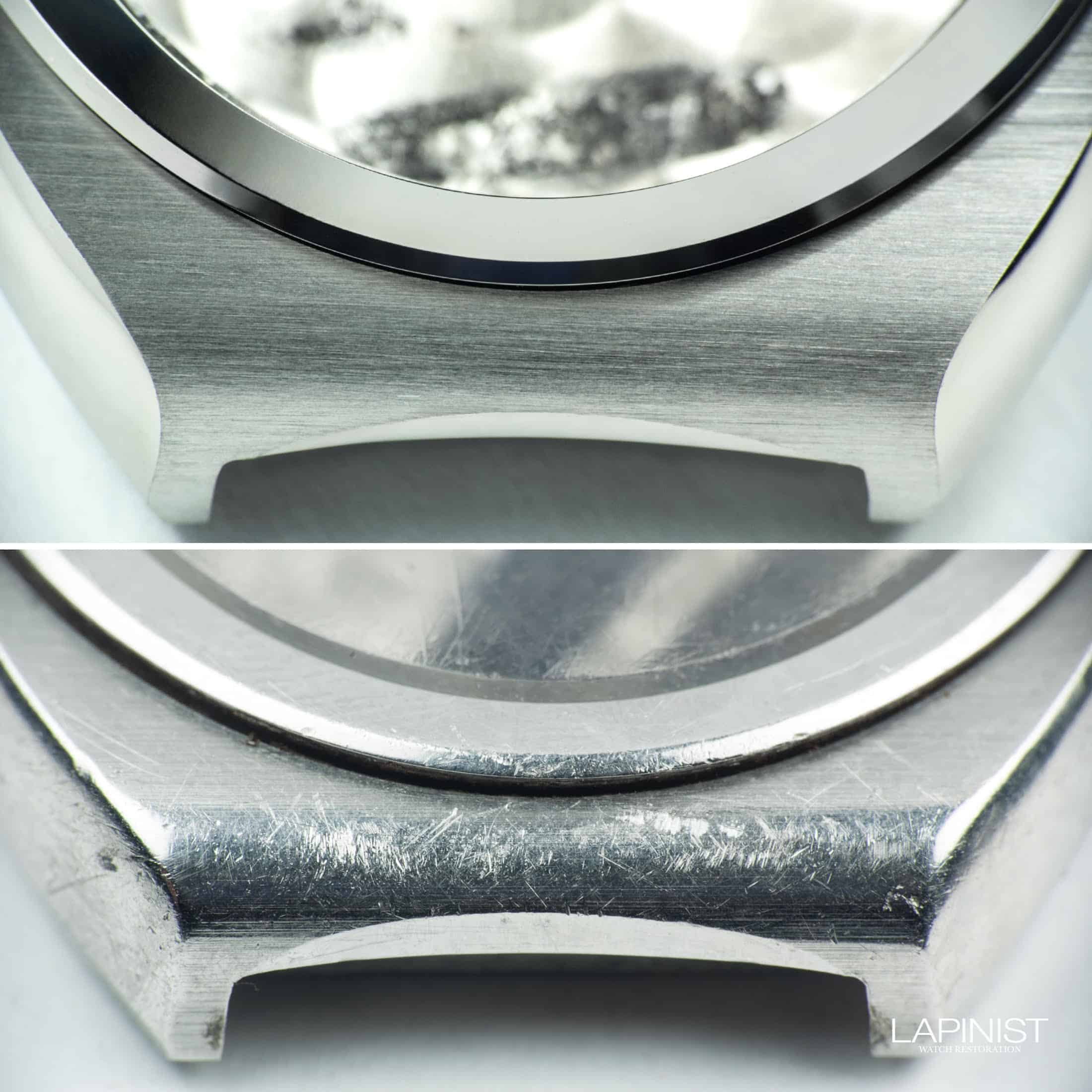

I stumbled onto Dunkowski’s work by accident. He has a small but growing following on Instagram (@lapinist_watchrestoration) where he showcases dramatic before and after photos of watches that have been sent to him from all corners of the world. It’s striking to see photos of beat up, seemingly-beyond-repair Seiko sports watches with close-ups of dings and scratches that might go a step or two beyond a desirable patina, alongside images of the same watch restored to catalog photography standards. There are videos, too, that showcase the unique characteristics of how a zaratsu polished lug, for instance, reflects light in motion. It’s something to behold, and a great Instagram follow if you’re a watch lover who appreciates excellent metalwork.

Dunkowski’s watch story is typical and will be familiar to many: at 18 he obtained his first mechanical timepiece, an inexpensive Seiko 5, and the rabbit hole was officially open. It wasn’t long before he graduated to more serious collector’s pieces in the Seiko range, and he gradually developed an interest in the unique Seiko style of case finishing. It was during the renovation of his personal watch, a Seiko 6139 chronograph, that everything clicked.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos