Our survey of international military timepieces is back in action after a long hiatus. In this installment, we travel to Italy.

World War II

Many are no doubt familiar with the dedicated dive watch and the military watch as 20th-century Swiss inventions, but such historicity is only partially accurate. It was in fact fascist Italy that played an outsized role in the development of early tool watches, paving the way for other European countries to follow.

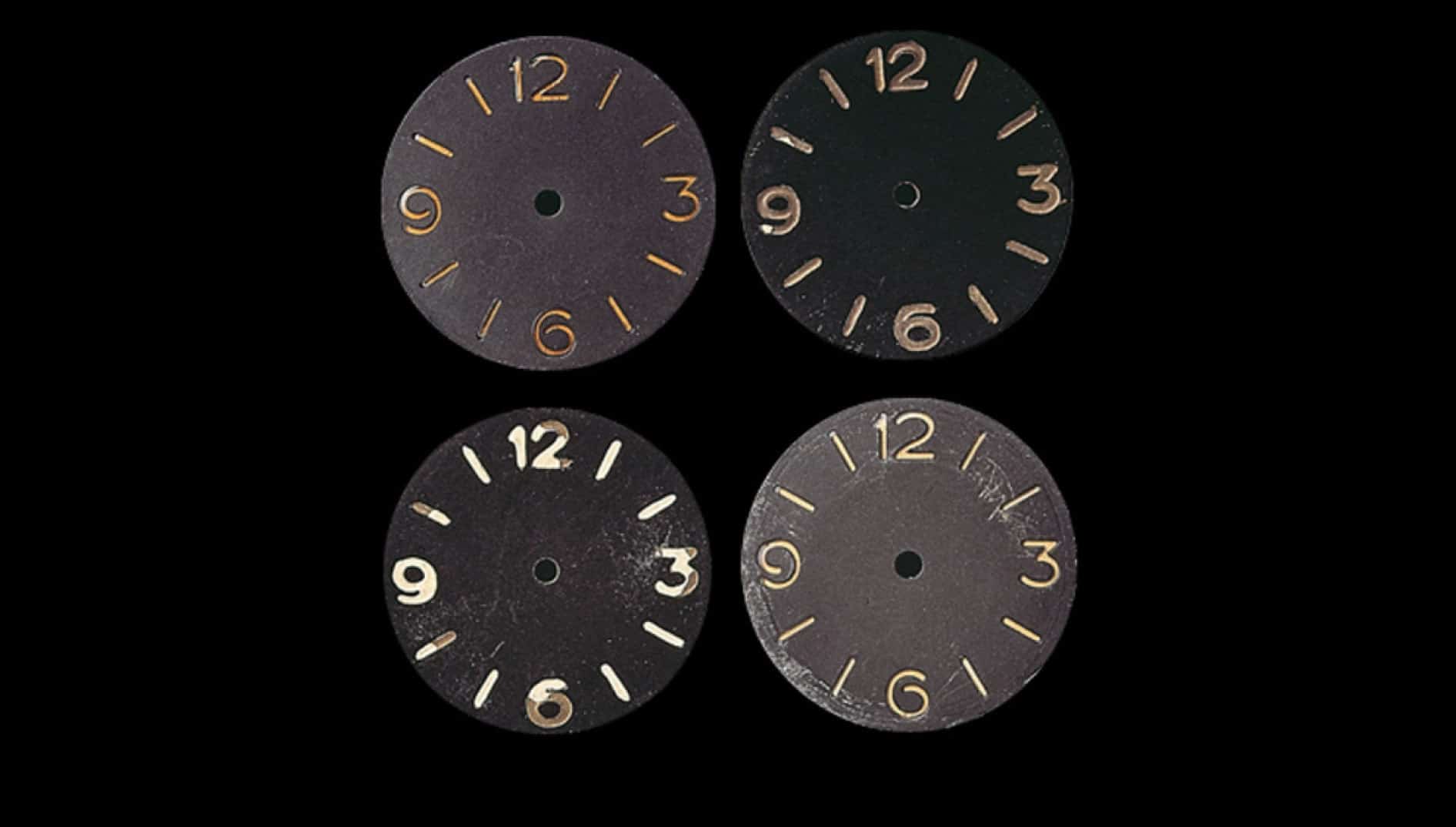

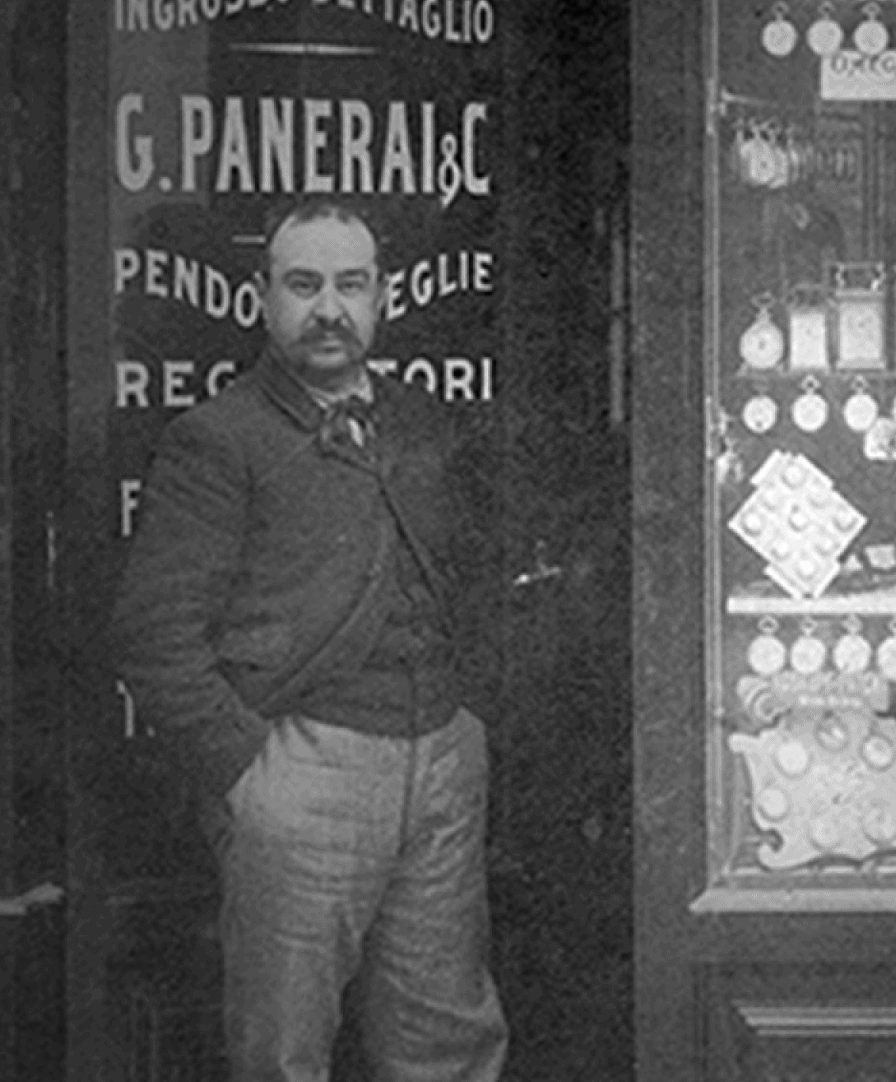

Giovanni Panerai founded his eponymous horological shop and watchmaking school in Florence in 1860, a year before the formation of Italy as a modern nation-state. His grandson, Guido, would expand the business significantly, and in 1916 developed a radium/zinc sulfide powder enclosed in sealed vessels. (Users of watches illuminated by modern, hermetically sealed tritium tubes will recognize the idea behind this early technology.) Panerai, which had already been equipping the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) with different types of equipment, adopted this new mixture for use in gun sights, precision instruments, and watches. Highly visible in low light given its radioactive makeup and adhesive even underwater, the substance was christened Radiomir, and would go on to form the basis of one Panerai’s most famed watch collections.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos