Vintage chronographs are a hot commodity right now and have been for some time, and it’s not looking like that market will be slowing any time soon. With prices soaring for well-known Swiss brands, some consumers and collectors are looking further afield to satisfy their desires. The vintage Seiko market has been growing steadily over the years as collectors realize the enormous value from particular models. The most popular of these would have to be the original 6139 series of chronographs.

The Seiko 6139 was produced in 1969, a big year for the automatic chronograph, as that was the year the famous Zenith El Primero was introduced, as well as the Heuer/Buren Caliber 11. The 6139 was a single-register chronograph, displaying elapsed seconds and minutes, and it came in two variants: the 6139A and the later 6139B, which replaced the A.

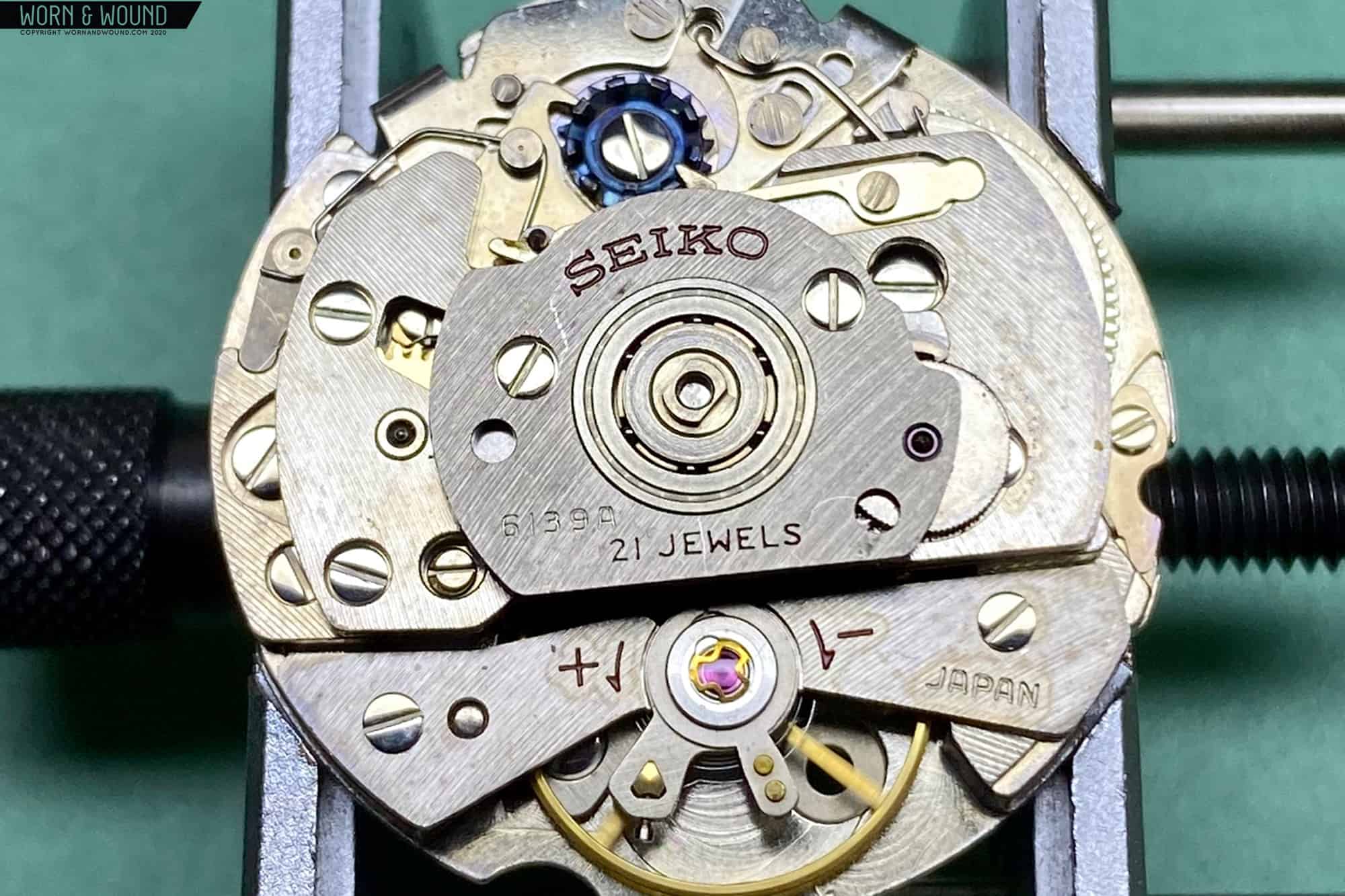

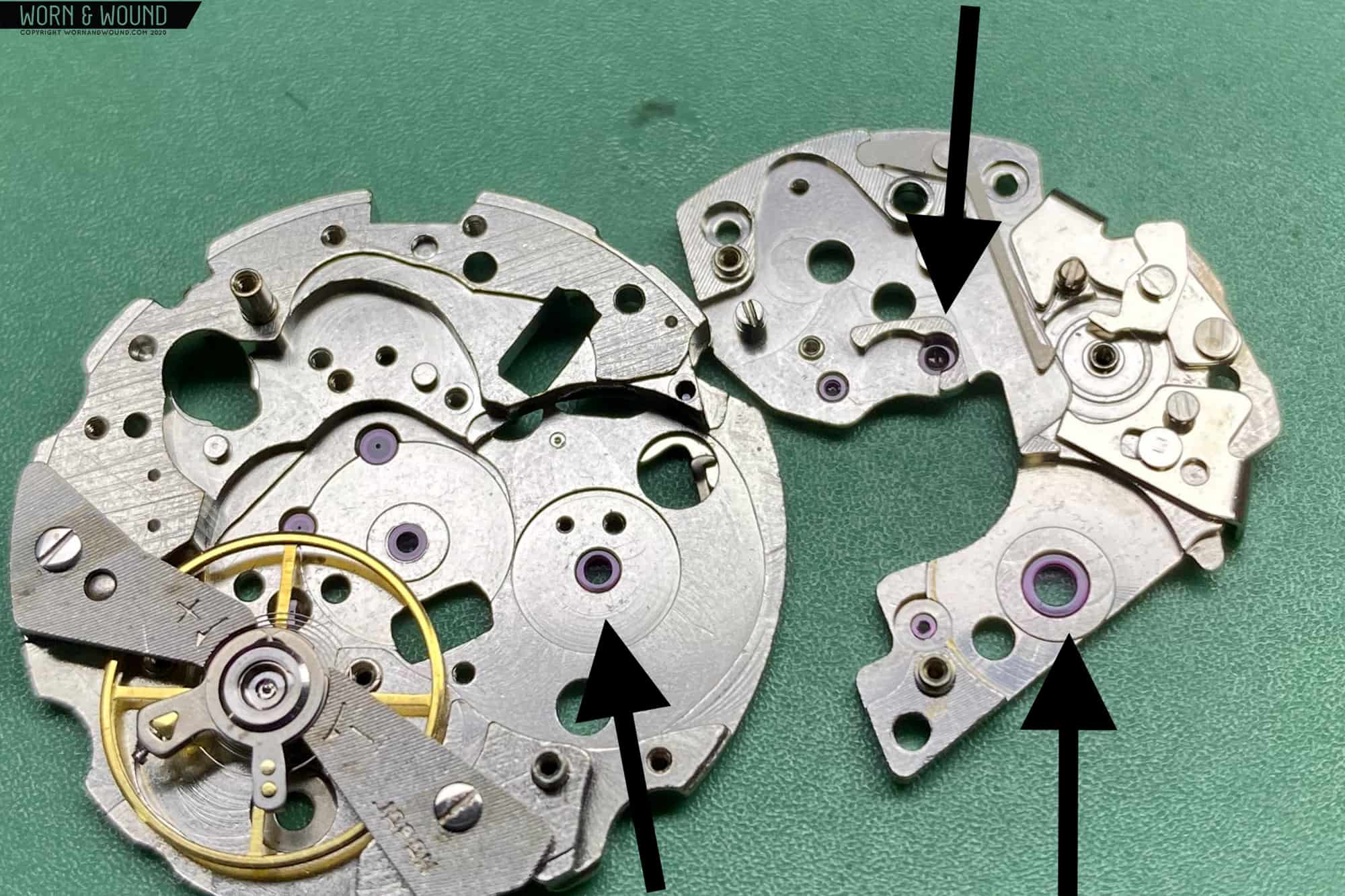

The watch under the microscope today is a Seiko 6139-7010. It features a “military” dial, as it’s rumored this watch was a Japanese Defense Forces-issued piece. This particular variant is the 6139B caliber with a 21-jewel count. A 17-jewel variant also exists, but I’ll get into that later. This watch was purchased by a Canadian Seiko collector (@canadianwatchguy) who sent it to me for a full overhaul.

Now, these 6139s tend to be solid, reliable calibers, and this watch wasn’t running terribly, but it needed some general maintenance, the crystal was scratched, and the bezel had been rounded due to over-polishing. With a NOS (new-old-stock) crystal and bezel sourced, I got to the movement.

The Breakdown

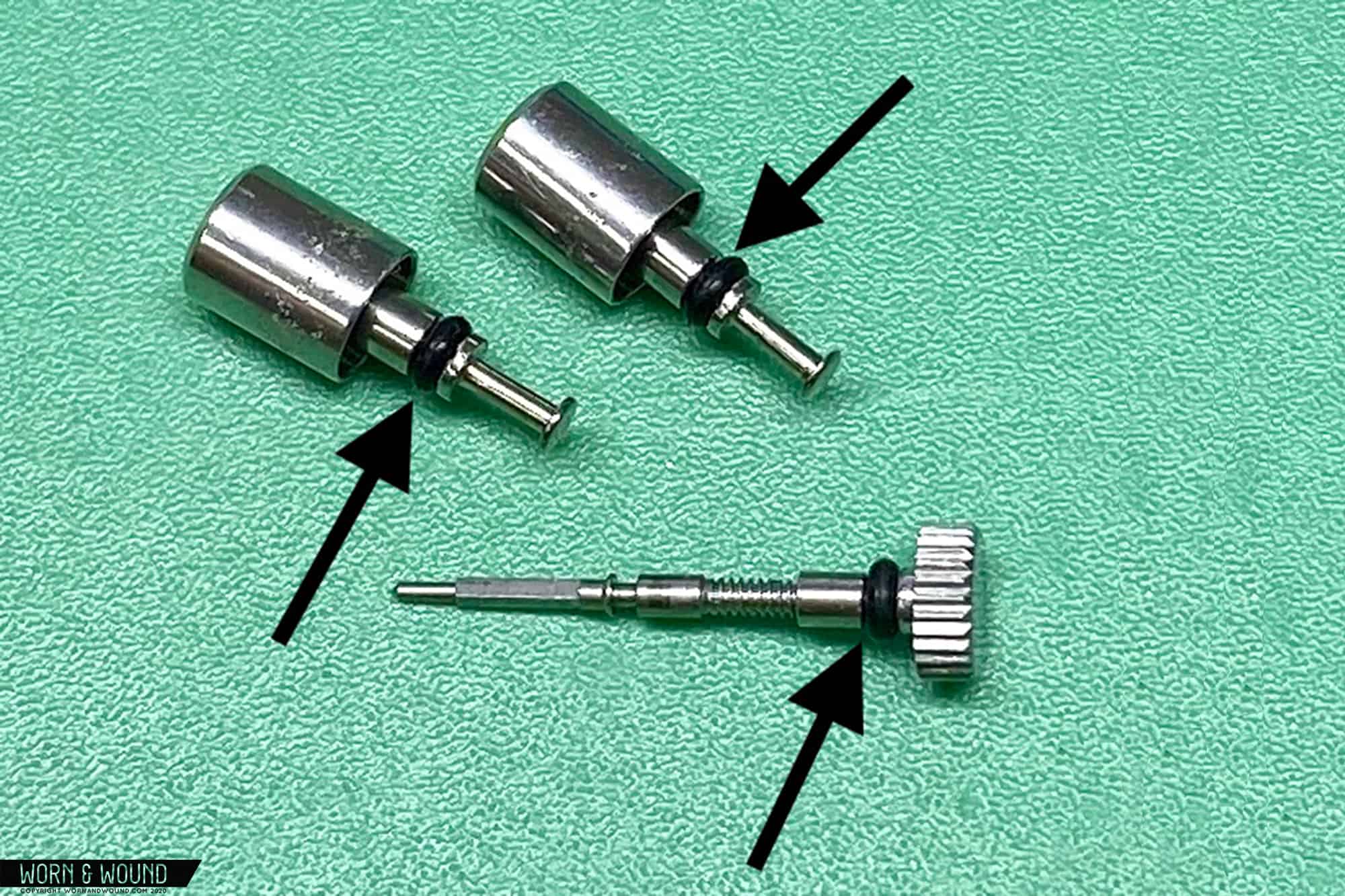

One of the most common issues Seiko chronograph’s face is sticking of the pushers and crown. If you are an avid Seiko collector, then I’m sure you’ve encountered this problem. The cause of this is either broken pusher springs or gaskets which have deteriorated over time.

This particular watch had another problem altogether. The previous watchmaker had installed three gaskets onto the crown, but there should only be one. This sort of reckless behavior is, unfortunately, all too common with unscrupulous “watchmakers,” who don’t care to obtain the correct profile pusher and crown gaskets. I rectified this problem (you’ll see my fix near the end of the of the assembly).

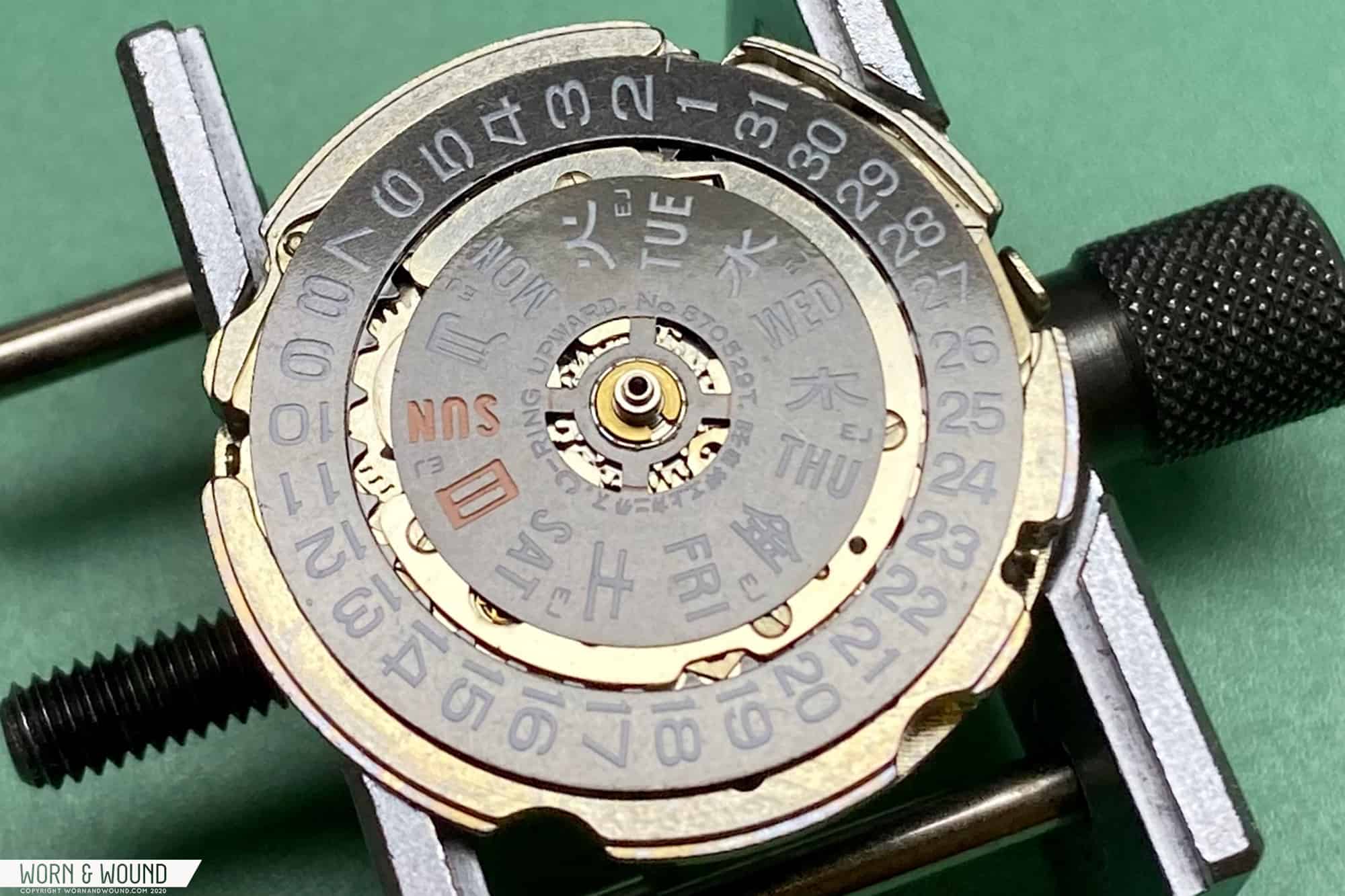

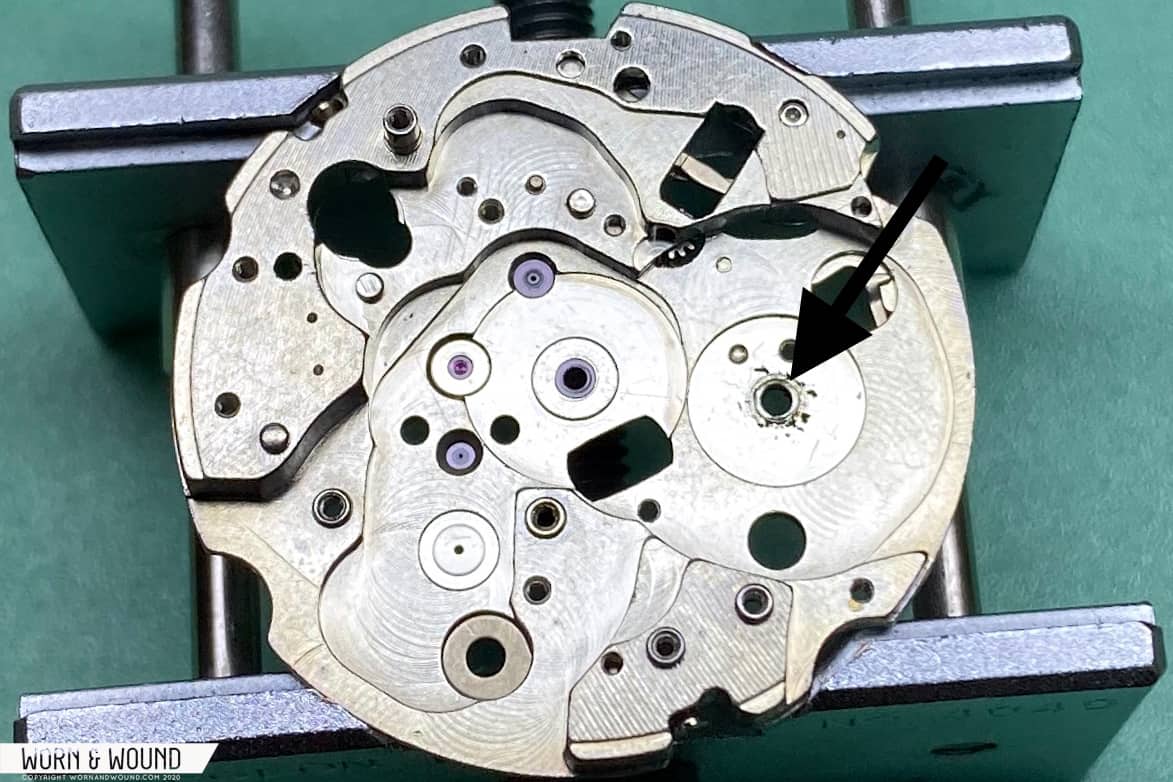

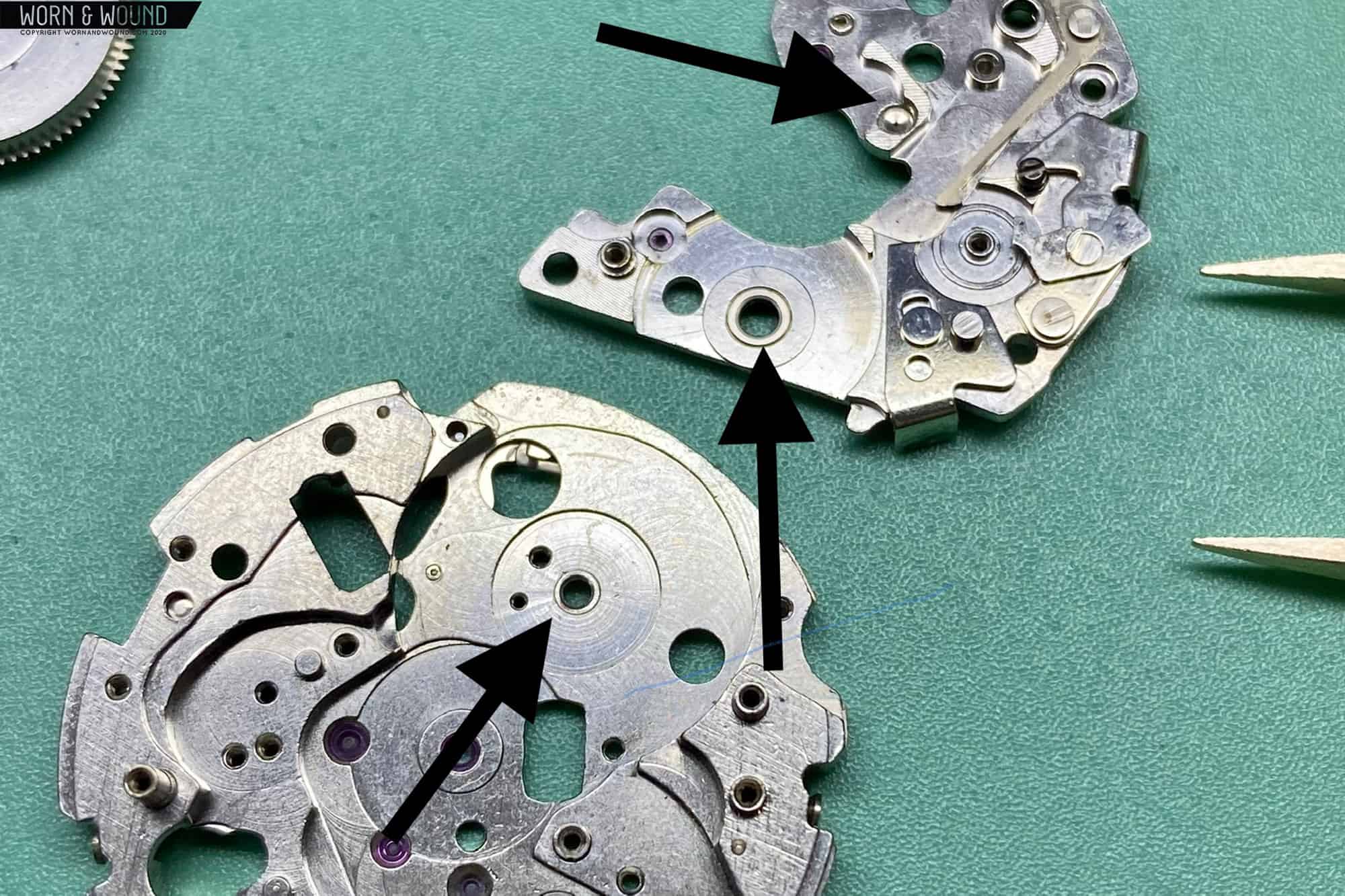

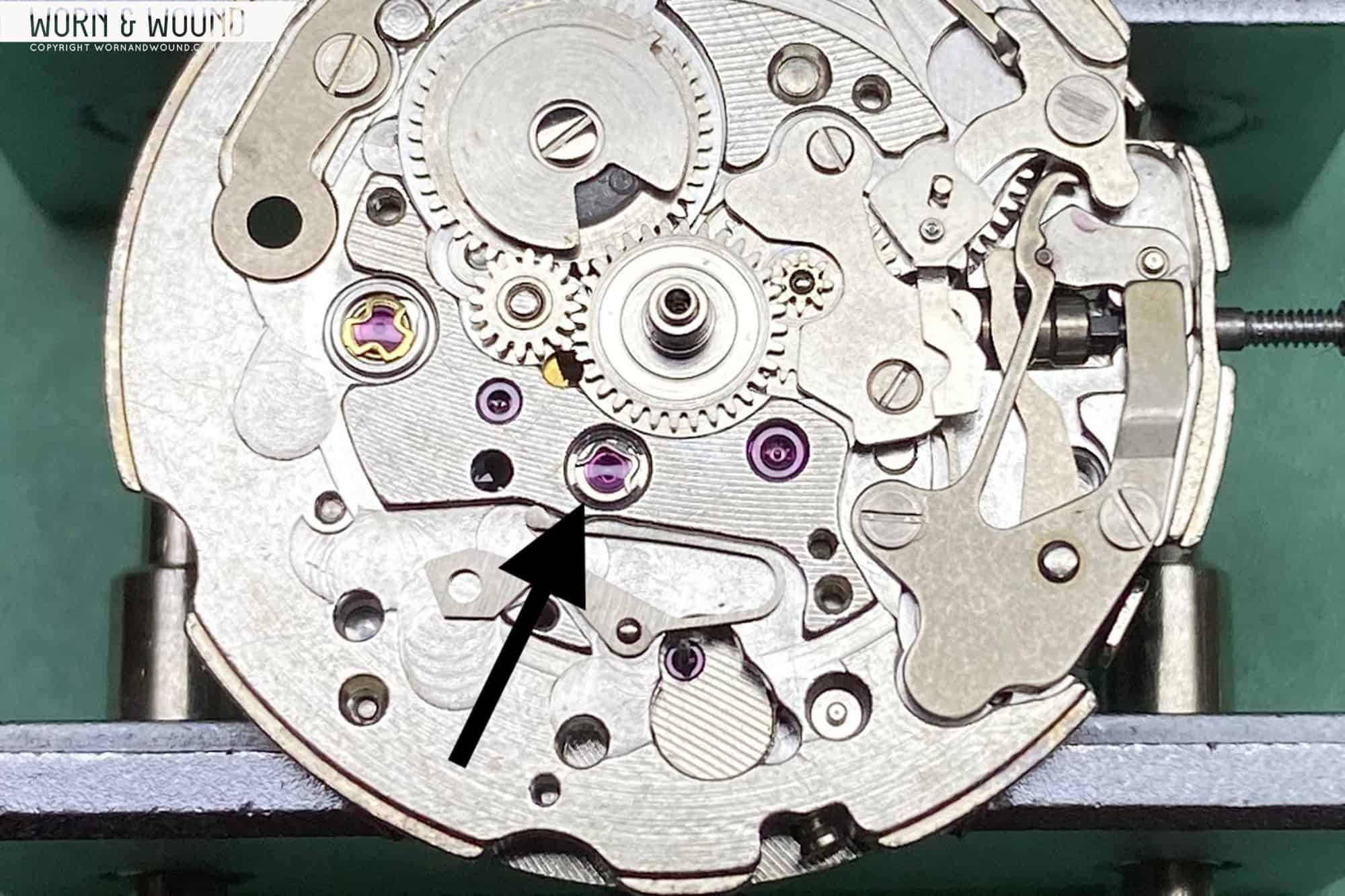

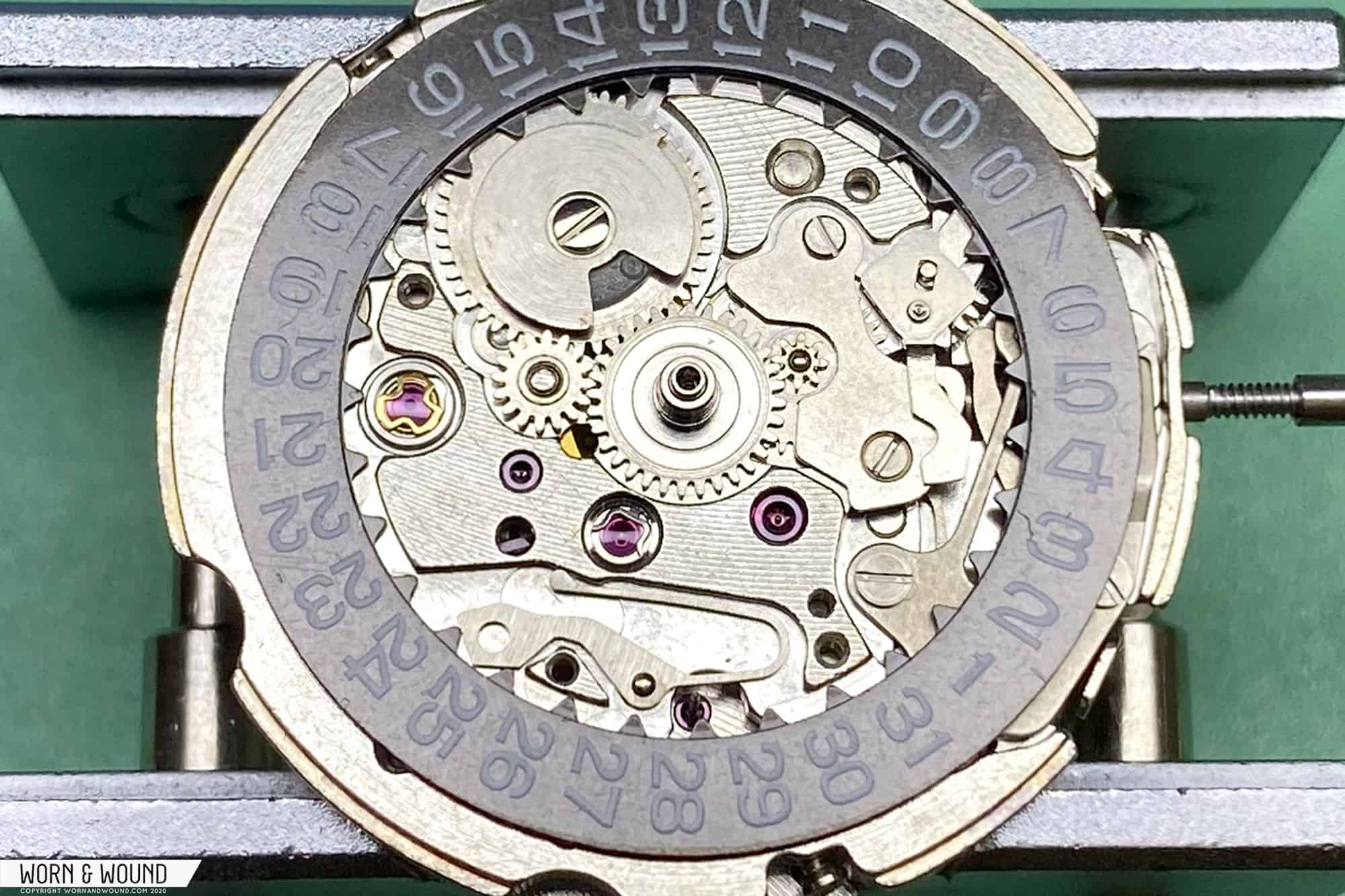

With that out of the way, a proper breakdown of the movement can begin. The first order of business is the calendar work on the top-side of the movement. First, we begin with the removal of the day and date disk.

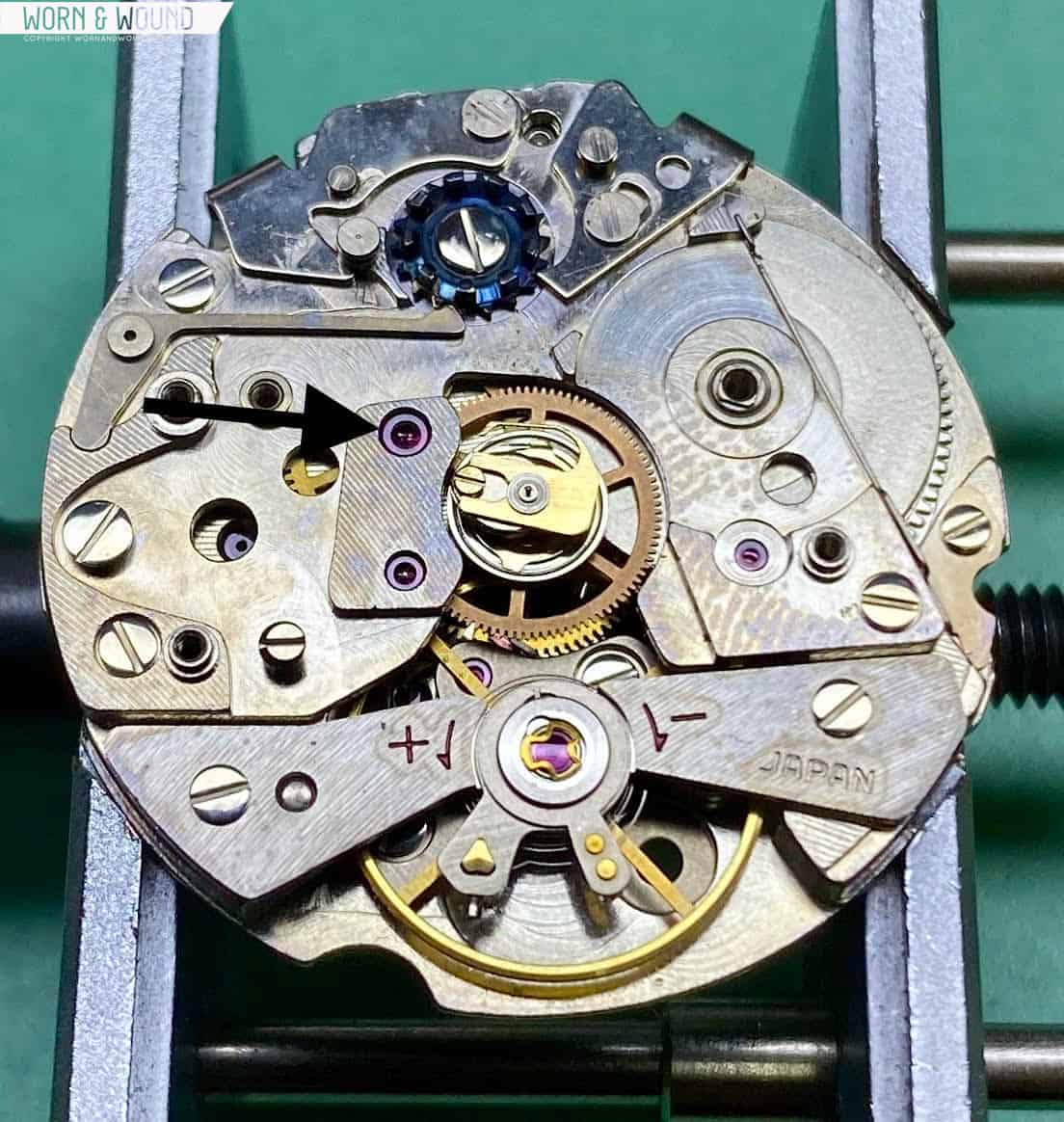

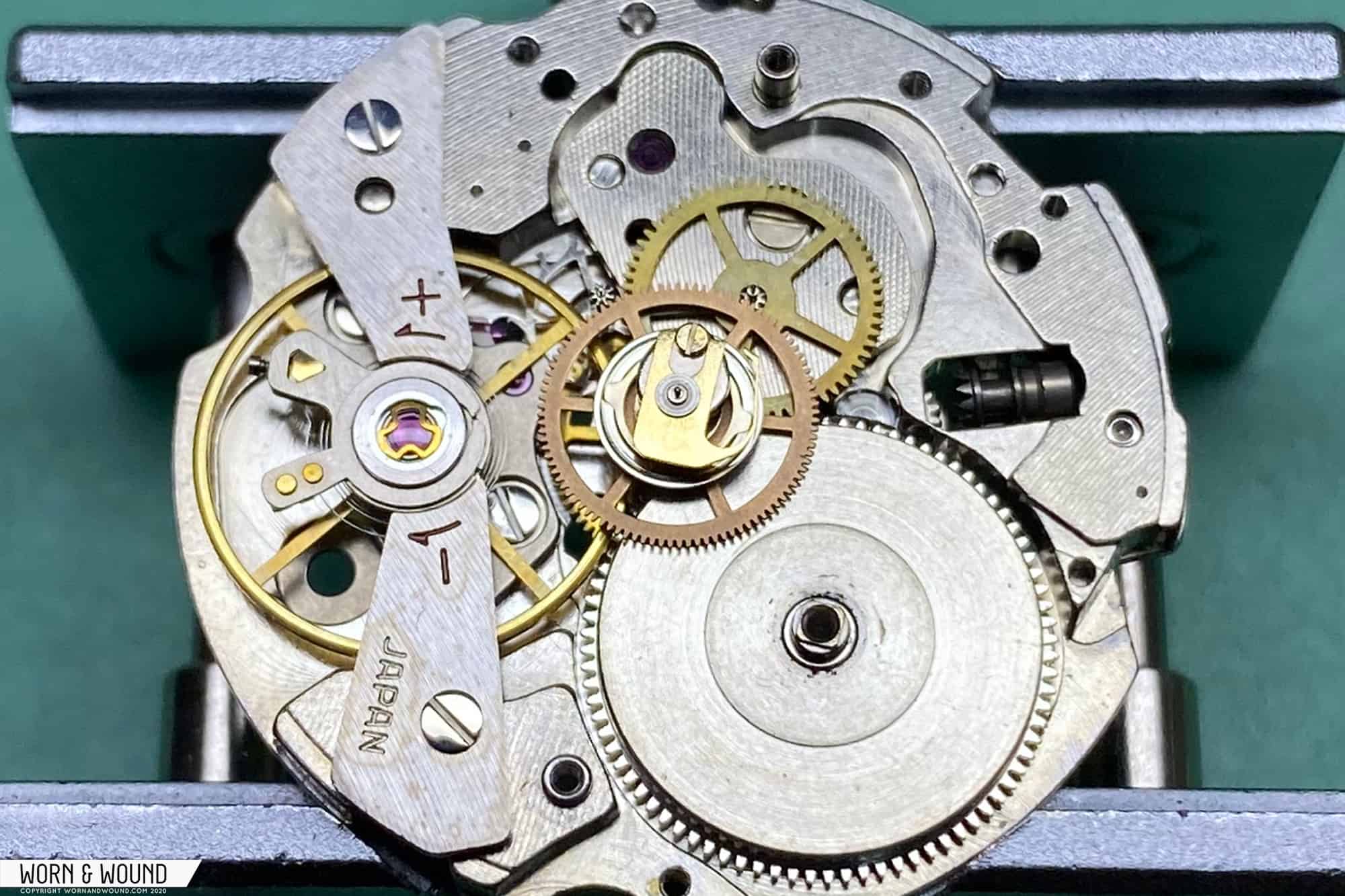

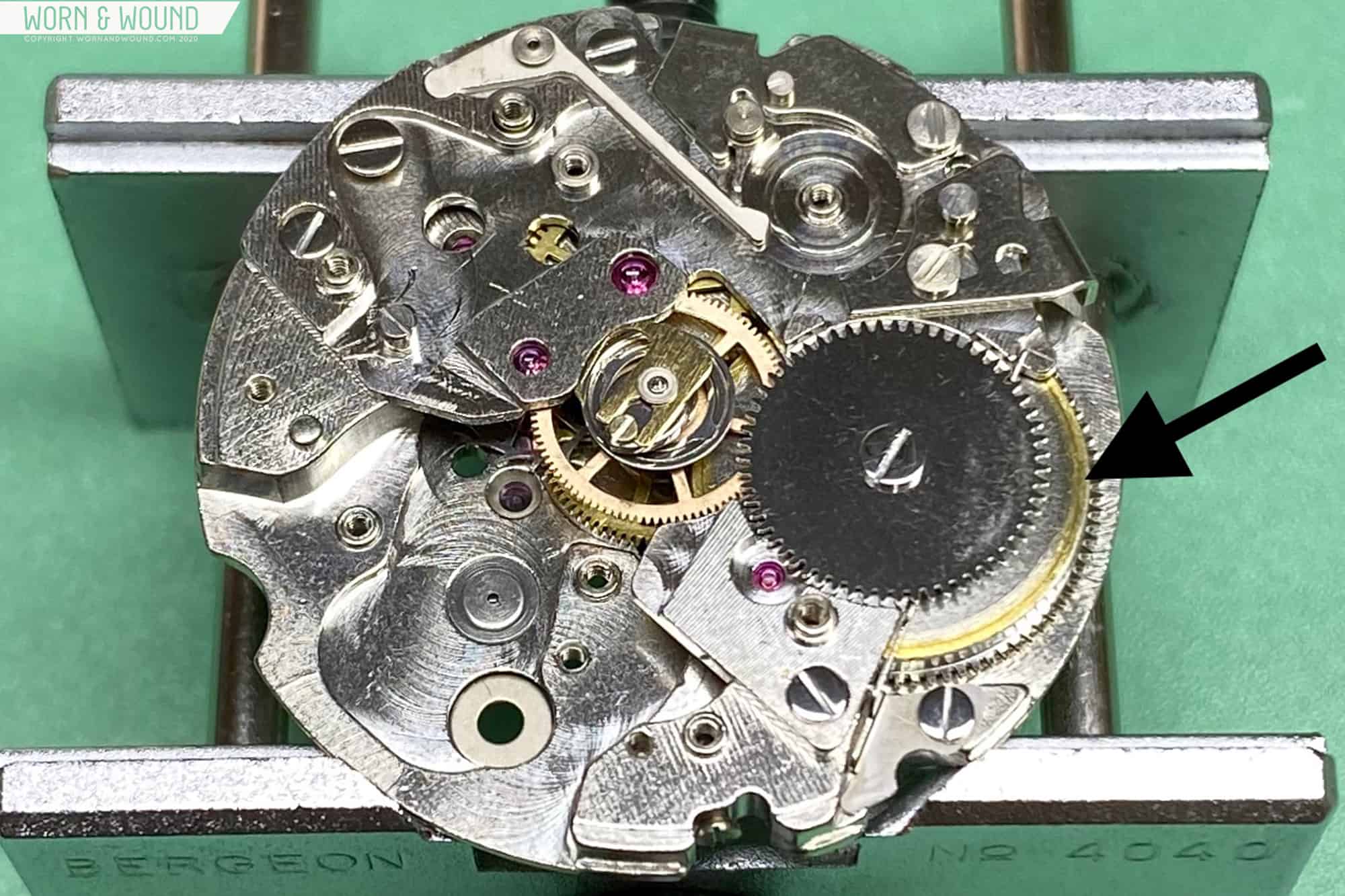

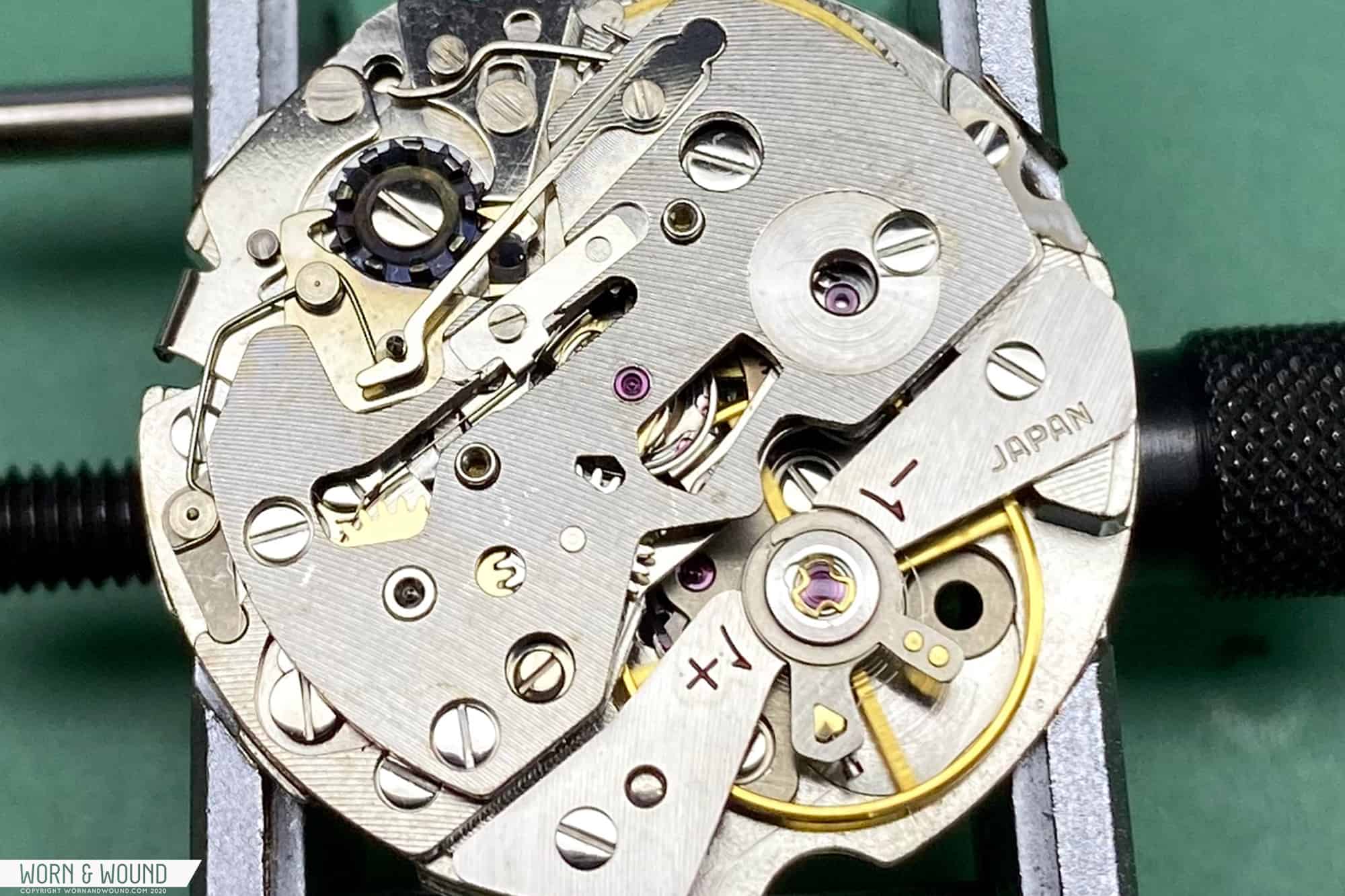

With that done, we can flip the movement over to the other side. Here’s what it looks like sans rotor.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos