A few weeks ago, we kicked off our Military Watches Of The World series with America Part 1, focusing on watches from World War I through the early ’60s. In Part 2, we’ll feature watches issued to the U.S. military from the Vietnam era through today.

Vietnam War

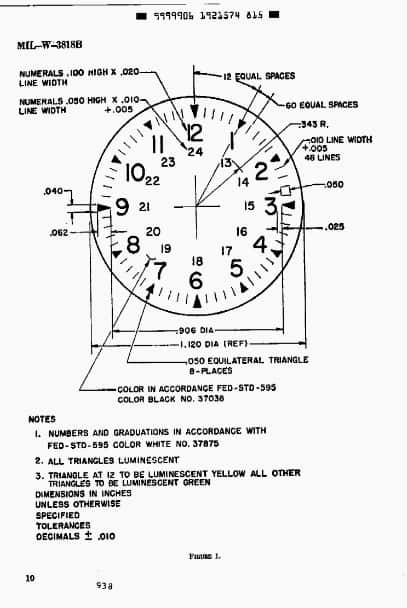

With the release of the MIL-W-3818B spec in 1962, the fog lifts once again and there is a clear, traceable history of issued watches. This revision was meant to simplify the requirements for a 17-jewel, hacking wristwatch with an extended service life, and the watch ultimately produced under this spec was the Benrus DTU-2A/P. It featured a parkerized steel case, a black dial with numerals and indices in white and an inner ring with military time, hands filled with green luminescent paint (tritium), an acrylic crystal, and an orange-tipped second hand also painted with tritium. The movement featured 17 jewels, hacking, a 36-hour power reserve, and accuracy of +/- 30 seconds per day.

The MIL-W-3818B grew into the GG-W-113, a spec released in 1967 that was nearly identical to the MIL-W-46374 A-D revisions (I’ll get to these next) and was issued concurrently for many years. The differentiation was that it featured exclusively a 17-jewel, manual-wind and hacking movement and a “sterile” dial for legibility. These watches were meant for issue to pilots and were produced by Benrus, Hamilton, Marathon, and Altus.

In 1964, the MIL-W-46374 spec was published calling for an accurate, disposable, and non-maintainable watch in either a plastic or metal case to be issued to infantry and other ground forces. Most of these featured the numeral “12” painted in tritium, though some examples exist without this detail.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos