While we certainly endeavor to cover a wide range of watches here on Worn & Wound, there’s no doubt that there’s a certain bent toward what many refer to as tool watches, or watches that are designed for a particular, functional purpose, as opposed to objects that are made purely for aesthetic pleasure. There are a lot of reasons for this – these watches tend to naturally fit into the price point we cover, for one. But ultimately it comes down to something as simple as “we like them.”

In the realm of tool watches there are many different technologies that are used to make these timepieces “tough,” in whatever way you want to define that term. This story is the first in a series where we’ll cover some of those technologies in depth, going through their history, the watches they’re used in, functional benefits, and a dive into the tech itself.

First up: watches with antimagnetic properties.

Mechanical watches, simply because of the materials that they’ve always been made of, are uniquely susceptible to magnetism. And magnetic forces, in our modern world, are everywhere. It’s no wonder that something of a cottage industry has sprung up around the production of watches and watch components that are resistant to magnetism. If you’ve had the unfortunate experience of dealing with a magnetized watch, you understand the value inherent in these technologies.

The classic symptom of a magnetized watch is unusually too-fast timekeeping. Balance spring coils, when magnetized, can stick together, reducing their travel back and forth, causing the watch to beat much faster than it should, resulting in timekeeping that will typically be noticeably off. Depending on the age and materials used in the watch, and the level of magnetism the watch is exposed to, a watch can even stop entirely when heavily magnetized, definitely a frightening moment for the wearer. Many, many objects produce magnetic fields. Loudspeakers, for example. Computer harddrives. Medical equipment. Even cell phones.

While it’s relatively simple to demagnetize a watch (tools that can easily do the job are easily purchased for well under $100 on eBay and elsewhere), that hasn’t stopped the biggest names in the watch industry from pushing the technological envelope as far as it will go. Telling the story of antimagnetic watches, it only makes sense to start with Rolex, the biggest name of them all.

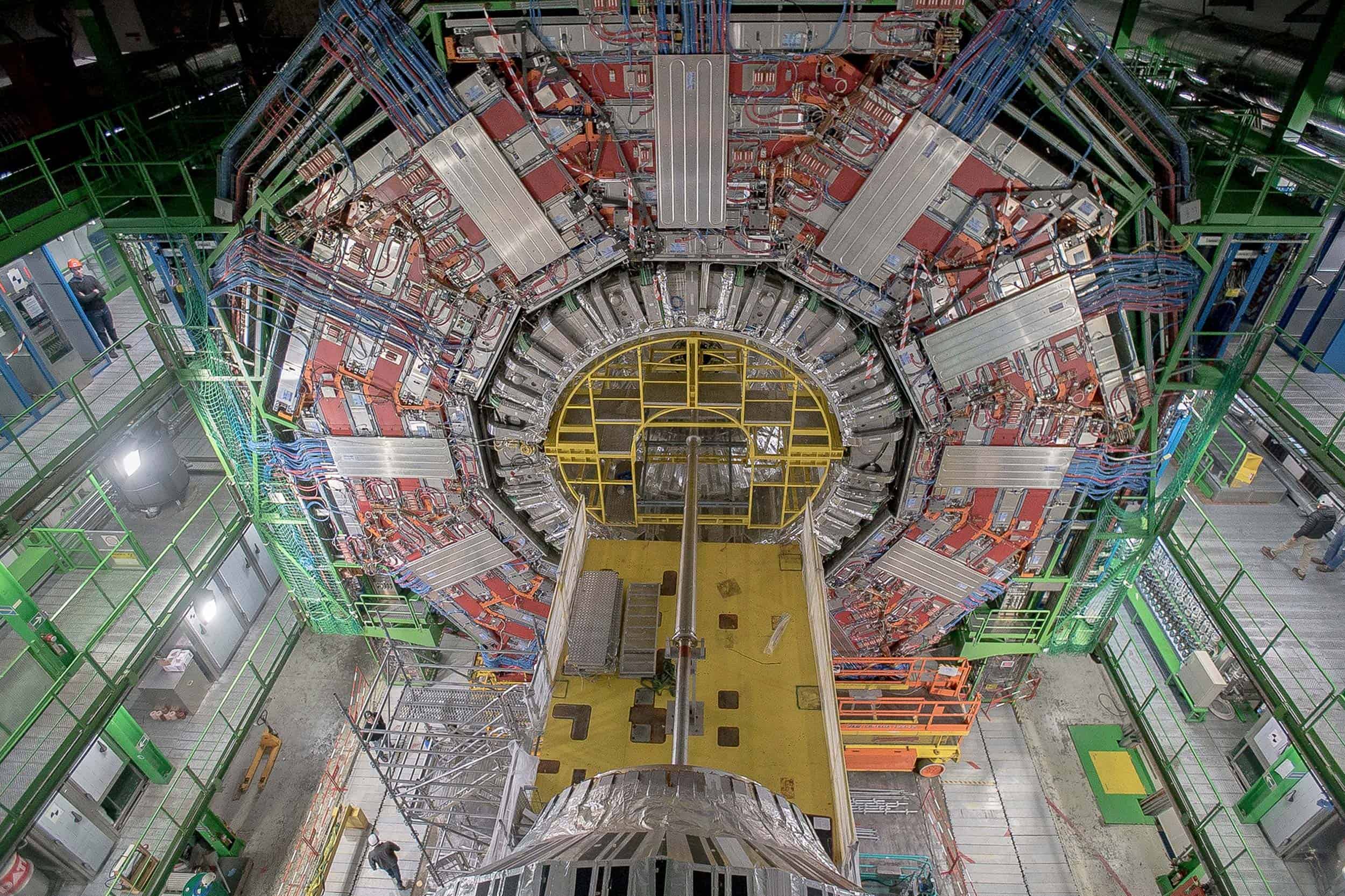

The Milgauss, Rolex’s stab at a watch for scientists working with the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), was introduced in 1956. That watch, the reference 6541, was rated to withstand magnetic fields of up to 1000 gauss. More typical watches of the time period could only handle magnetic fields of around 50-100 gauss, so this was a significant improvement. Rolex achieved this high level of magnetic resistance by enclosing the movement in a soft iron cage, also known as a Faraday cage. This method put a relatively simple scientific principle to work in the Milgauss, and is still the standard for making watches with high levels of anti-magnetism. Faraday cages can be found in watches by Sinn, Damasko, Bremont, and other brands.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos