Judging by the fact that this article is part 3 of a series, it’s fair to say that the Poljot Strela was not the first watch in space, but in a very real sense it is. The Shturmanskie on Yuri Gagarin’s wrist, or the Breitlings and Heuers of Scott Carpenter and John Glenn, did leave the atmosphere and orbit the earth, but always in the safety of a sealed capsule. When Alexey Leonov stepped outside Voskhod 2 at 12:34 PM on March 18, 1965, he took a quantum leap forward in human endeavor- for the first time, a human being exposed themselves directly to the hard vacuum of outer space- and timing every moment of that first spacewalk, the Strela.

Alexey Arkhipovich Leonov was a more delicate, nuanced man than many in the Soviet Air Force’s First Cosmonaut Group recruited in 1960. As opposed to military men and model Communists like Gagarin, Gherman Titov, or Vladimir Komarov, Leonov trained as a painter and was popular among his fellow trainees in the First Cosmonaut Group for his quick and often pointed sense of humor. Despite this, Leonov remained one of the program’s most promising prospects, and was originally scheduled to fly on Vostok 11 before the Vostok program was cancelled. Alongside Leonov on the March 18 flight was Major Pavel Belyayev, the old man of the First Cosmonaut Group at age 39, and the ranking officer of the Soviet cosmonaut corps. It would be the first spaceflight for both men.

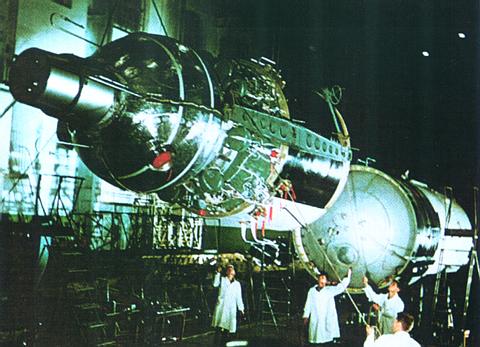

Voskhod 2 was by far the most ambitious project taken on by the Soviets to that point, and the complexity of the mission manifested itself in difficulties from the moment the craft ended its first orbit. 90 minutes after liftoff, after Voskhod 2 had completed its first trip around the planet, Leonov depressurized and opened the capsule’s airlock, and encased in the as-yet-untested Berkut (Golden Eagle) model space suit, stepped out into the cold emptiness of space for the first time in human history. Almost immediately, the suit began malfunctioning, and while Leonov was able to attach Voskhod 2’s external camera, by the time he reached down to use his own handheld camera his suit’s joints had inflated and stiffened. His ballooning suit left him unable to bend down to reach his camera’s shutter button, and the problem continued to worsen throughout the 12 minute and 9 second EVA.

When the time came for Leonov to re-enter the capsule, the suit was so rigid he was unable to maneuver himself into position and entered the airlock sideways. Leonov was forced to manually depressurize the suit inside the airlock in order to regain movement, a move that Belyayev warned could cause a potentially fatal case of the bends, but after several minutes of struggle Leonov managed to bend well enough to return to the capsule. While much of the air inside was purged, Leonov’s suit was still reportedly filled to the knees with sweat as the astronaut had suffered an attack of heatstroke during the spacewalk. With inflated suit joints still making his movements cumbersome, he took an additional 46 seconds past schedule to return to landing position in the capsule. At the immense speeds the Voskhod 2 orbiter was traveling, this translated to an overshoot of their intended landing zone of roughly 200 miles, with the craft finally coming to rest in a heavily wooded part of the western Urals. Belyayev and Leonov, equipped with a pistol inside the Voskhod 2 lander, were forced to fend off hungry bears and wolves, as well as bitter sub-freezing cold, for over a day before a rescue party finally arrived on skis.

Overall, however, the mission was touted as a huge success by the Soviet government, and the title of first spacewalk became another major Communist propaganda victory over the United States as the Space Race continued to heat up. And for all the malfunctioning equipment Alexey Leonov was forced to deal with, one of his most crucial pieces performed admirably through extreme g-forces, brutal mountain cold, and the vacuum of space- his personal Poljot Strela chronograph.

The Caliber 3017 Strela, standard issue for all Soviet Air Force pilots and cosmonauts from 1959 until its eventual phasing out in 1979, was a rugged, reliable piece of hardware with a densely-packed, but still attractive dial setup. Leonov’s model was especially handsome, a white dialed example with applied gold numerals at 12 and 6, narrow gold wedges at 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 11, and simple gold stick hour and minute hands. The two-register chronograph functions are supplied via a 45-minute counter at 3 o’clock and a running seconds at 9. To my eye, however, the defining features of this watch are the concentric register tracks, from the outer tachymeter and minute register to a contrasting blue telemeter circle sitting comfortably inside the hour markers.

This arrangement allows for a wealth of important information without coming off cluttered, and adds a touch of offbeat Soviet personality to an otherwise normal setup. At 37mm, it is a touch on the small side for a chronograph, but with the general trend toward smaller watches along with its vintage design it shows extremely well. It’s a versatile watch and a good candidate for a daily wear, looking equally at home on alligator as it does on olive nylon. Prices on Caliber 3017 examples seem to be moving up in recent years, with prices ranging between $600-1100 depending on condition. If originality isn’t such a concern, however, Poljot/Maktime produces the Strela to this day with the venerable Caliber 3133 for $620.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos