Most of the time, your watch will tick happily for years. Unless you own an Uhrwerk 105M or a vintage Rado, you probably don’t have a service indicator to tell you it needs help. But slowly, over time, the fractional quantities of light oil in each bearing evaporate and harden. As they do, friction and wear increases, perhaps helped along with the incursion of a bit of dust creeping past the seals to act as grinding paste. This is not good.

That’s without the accidents that can befall watches: toddlers knocking them from shelves onto stone bathroom floors, scrapes in motorcycle accidents, crystals shattered by the impact of a stiletto heel (don’t ask).

And that’s when you need a specialist watchmaker. These are the people who make the plate glass boutiques and smart brands possible. They don’t often get the glory, but they certainly do the work.

Looking inside the case, it’s not hard to see why. That automatic watch on your wrist has around 200 precision parts ticking away. Even a basic analogue quartz has between 50 and 100. A standard case will have anywhere between three and perhaps five. Even straps aren’t simple. If you’re posh enough, a woven gold Milanese strap can have hundreds of links, and even a standard leather has around seven parts – count ’em. All that adds up to a lot of complexity.

Tony Coe, Simon Freese and their team at Swiss Time Services (STS) are serious watchmakers. Visit their workshop in Essex and you won’t spot a lot of chrome and plate glass but you will see proper watchmaking and engineering in action.

If you prefer your watchmakers to have substance over the bling of Bond Street, STS’ workshop will come as a pleasant surprise. There are no flunkies to open the door for you and you won’t often see a Bentley outside. But inside it’s Omega heaven.

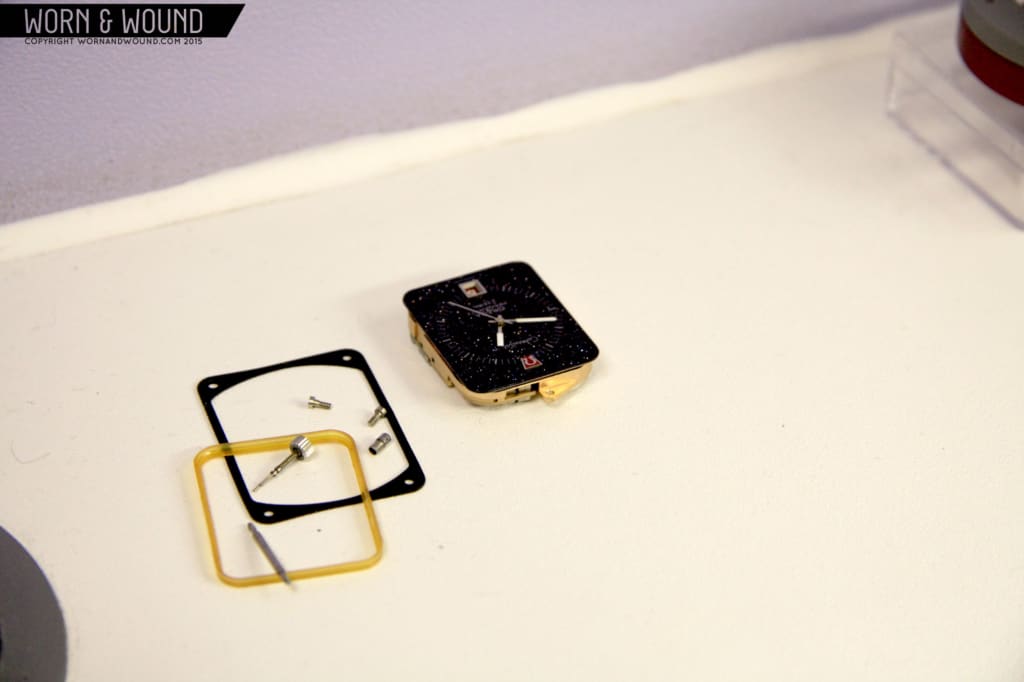

Walk up to reception. The casual observer will see a few old Omegas around the place. The initiated will spot they’re nearly all new old stock and some rare as a Richard Mille discount. For example, there’s a caseful of unusual Speedmasters including the cal. 1620 digital. You’ll spot a Marine chronometer or two. A perfect, uncracked stardust dial Megaquartz Constellation. There’s plenty to keep waiting watchies amused.

Simon Freese is STS’ Workshop Manager. The bald title tells you a little about how the business works; this is about craftsmanship not titles, brand and marketing puffery.

Meeting Simon, you realise he has a brain that actually runs a datafeed direct from Omega’s Bienne database. He reels off model numbers and calibre references so easily that you get the sense he could diagnose a problem with your watch while it was still on your wrist. In another county. But he does it in a way that involves, rather than intimidates. He clearly enjoys passing on his knowledge; a good job with his growing team of 30 watchmakers.

Simon got into Omega young. His father had an Omega and it fascinated him, “It was discrete, subtle even – it didn’t shout.” He’s seen a lot of changes in the 12 years he’s been with STS. “Back when we started there weren’t many people collecting watches. We repaired the watches people wore every day. Now people are looking at things like case and bracelet refinishing and restoration.”

Tony, STS’ owner, worked with Omega almost straight from school. “I played around with project watches at school, then started in the ’70s at Omega’s Leicester service centre.” he remembers. “When I went out on my own in 1993, old watches weren’t a thing. But we began to get a reputation for Omega work and Omega began referring work to us on the watches they couldn’t fix.”

Tony’s first workshop was in Southend, then he moved to Hockley and has taken over the current building bit by bit. There’s now 17,000sq ft of space and even a jeweller on the premises for goldwork.

Eight years ago, Tony set up Swisstec to work on other brands, and now looks after Ball and Ebel (the latter a brand Tony describes as “seriously underrated”) in the UK. They work on other brands too and you’ll see plenty of Rolexes and Heuers around the workshops.

And they’re certainly worth looking around. If your mental image is of wizened old watchmakers picking blued hands out of their long white beards, leave it at the door. The place is light, airy and stuffed with more technology than NASA. And the watchmakers range from their early 20s up.

When your watch arrives or you bring it in, it gets booked in and HD photographed. The shots are automatically saved too, so the team can get a firm idea of ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Then, Simon or one of the team will lift the bonnet and start diagnosing so they can determine what needs doing. “We’re guided by the customer,” Simon explains. “Some want a complete case refinish, so their watch looks as though it’s just left the shop. Other people want to keep the scratches and dings as the watch’s history and for us to service or repair the movement.”

Once you approve your estimate, the team gets to work. The movement is uncased and heads for the workshop where it’s stripped, checked, repaired and ultrasonically cleaned. The case goes for cleaning (and refinishing, if that’s what you’ve asked for). And if customers want to talk to the watchmaker working on their watch, that’s fine.

It’s worth spending some time in the case refinishing area. STS has made the decision to invest in some serious polishing and lapping kit. That means even a properly Lazarused watch case can be brought back from the dead. The technicians can micro-weld in new metal, polish it back and then lap the case so it has the original factory-style finish.

Once it’s cased up, the watch then gets re-regulated and tested for 48 hours before it’s photographed again, protectively packed and sent back to its owner, registered and insured.

But the workshop is only half the story. Tony’s Omega collection is the other. It is, shall we say, ‘comprehensive’. Being lucky enough to get a look at it is like time-travelling back to the Nürburgring in 1972 and being driven around by Derek Bell in his 917.

If Tony ever decides to open an Omega museum, there’ll be queues of salivating watchies around the block. Imagine…

For anyone into 1970s quartz and electronic, it’s heaven. How about a new, old stock Omega Time Computer I with its setting magnet still in the clasp? Or a 1602 Constellation, the TC II?

If digital isn’t your thing, how about this trio? A Constellation Electroquartz F8192 next to a cal. 1302, smoked crystal Beta 21. On the right is one of only 9,000 18ct Beta 21 Electroquartz cal. 1300, 13 jewel movement watches.

Stardust dial Megaquartz? Yep. Got a few of those too. This one with an immaculate dial (made by coating a thin, metal and fibreglass base with a layer of Aventurine quartz crystal dust). Those beautiful dials have a marked tendency to crack over time.

Mk I and Mk II Marine Chronometers? The most accurate quartz watch ever and a quartz crystal oscillating at 2,359,296MHz – that’s 72 times faster than the quartz you might have on your wrist. How about one that still has the plastic on the clasp because it’s never been worn?

Tuning fork watches? Of course, sir. Here’s an unworn cal. 1250 “f 300” with a 12 jewel movement.Max Hetzel, the engineer behind the Bulova Accutron, also designed the f.300 and they’re superbly high quality.

Fed up with all this love for things crystalline or humming? How about this one? An unworn original Seamaster PloProf. Ref. ST 166.0077, cal. 1002 and a proper diving tool, waterproof to 600m. This one’s never even seen a bathtub.

If Railmasters are your thing, Tony’s got a few – like this cal. 286 with its 17 jeweled movement.

Tony can bring out remarkable watch after remarkable watch until your thoughts start to stray to how many you could pocket and escape with. You’d need big pockets, mind. And your chances of making it past the security systems wouldn’t be good.

The watches keep coming, rarer and more fascinating by the minute.

As Tony and Simon take each one out of its case, there’s even mechanical sympathy in the way they put it carefully down on the table without a sound.

An 18ct gold-cased Omega Synchrobeat with its ‘1 tick per second’ deadbeat complication emerges from the box. Not heard of those? You’re not alone. Whether the rumours about there being fewer than 20 in existence are true, you’re more likely to find a digital Patek.

The final watch to emerge may have been the most remarkable. A cal. 28.9 enamel dial chronograph. First made back in 1932, this was the watch that paved the way for Omega’s success in chronographs. Lawrence of Arabia had an early model, as did aviatrix Amelia Earhart.

Viewing this collection, one realises it is actually possible to become watch-drunk.

It’s the sort of collection you don’t build up unless you have watch oil in your veins. Although the financial worth must give Lloyd’s underwriters permanent insomnia, Tony clearly values each piece as much for its horological interest. It’s a joy chatting with – and learning from – both Tony and Simon.

And, in the interests of research, I left my ’69 Chronostop behind for a complete overhaul and service after it got water damaged, camping at Le Mans. It came back perfect complete with all the original parts STS had replaced. My vintage Heuer Autavia’s just been dropped off for the same treatment.

It’s a definite ‘recommend without reservation’ from me.

For more on STS, visit: www.swisstimeservices.co.uk

Featured Videos

Featured Videos