In December last year, Jean-Daniel Pasche, the Chairman of the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, talked about how his organization seizes and destroys around one million counterfeit watches each year. He explained how, in 2016 alone, the Federation had seized nearly 130,000 fakes in Turkey, 70,000 in Dubai and another 9,000 in Russia.

The Swiss take counterfeits and counterfeiters very seriously indeed.

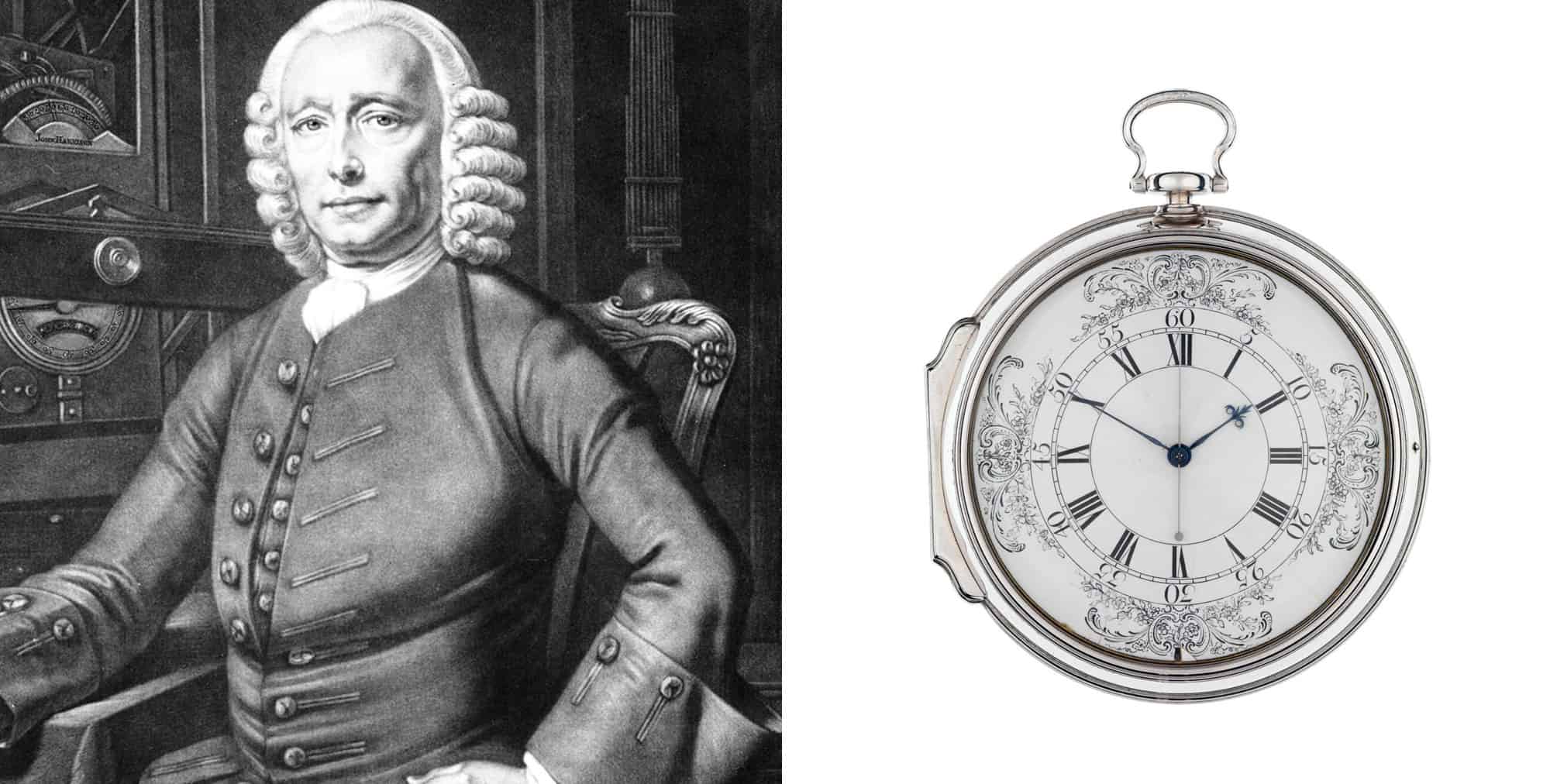

Yet, it was Swiss fakes of English watches that helped bring down the British watchmaking industry in the eighteenth century. Horologist and researcher, Dr. Rebecca Struthers has spent the last eight years unearthing their story and it’s one that involves forgery, smuggling and even the English parliament.

She describes how she first picked up the trail that would lead her from Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter to the Swiss border. “It all started when I was working at an auction house in the Jewellery Quarter (Fellows & Sons) whilst studying my MA History of Art and Design at Birmingham City University’s School of Art back in 2008. Whilst cataloguing some antique watches I came across one made in around 1760 that, despite being signed as London-made, looked completely unlike the London watches I was familiar with.”

When Dr. Struthers began following the trail, though, it quickly went cold.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos