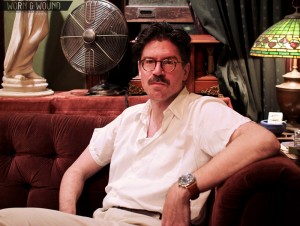

Meet David Sokosh, proprietor, designer and crafter of the Brooklyn Watches line. We first met David at the Brooklyn Flea, an eclectic collection of vendors that runs year-round in Fort Greene and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. We were immediately drawn to the classic aesthetic of David’s watches, so we inquired about the details.  That’s when we realized just how unique these pieces are. A vintage Unitas movement that David has found and restored himself powers each watch. The cases, dials and hands are a mix of custom and stock pieces that David sources and then assembles. Distinctly of a different era, but with some modern details, the watches exude a timeless elegance that fits in perfectly with today’s trends towards heritage fashion. You’d assume that these unique pieces with vintage movements cost a small fortune. You’d be wrong. They average in the $500 – $700 range, a great price for such exceptional watches.

That’s when we realized just how unique these pieces are. A vintage Unitas movement that David has found and restored himself powers each watch. The cases, dials and hands are a mix of custom and stock pieces that David sources and then assembles. Distinctly of a different era, but with some modern details, the watches exude a timeless elegance that fits in perfectly with today’s trends towards heritage fashion. You’d assume that these unique pieces with vintage movements cost a small fortune. You’d be wrong. They average in the $500 – $700 range, a great price for such exceptional watches.

David was nice enough to sit down with Zach and me to chat about his love of all things antique, his history with horology, and of course, his outstanding timepieces.

Worn&wound: How did you get into watch and clock restoration? What drew you to those industries and how did you get involved?

David Sokosh: I apprenticed with a clock maker when I was about 20. I worked with him for a couple years in Connecticut, and then went back to school for photography. Then I came to New York and worked in the photo industry for a long time, and always did clock repair and restoration for myself and for other people as favors.

I ended up owning an art gallery in Dumbo, which was three years old in the Fall of 2007 when the economy just collapsed. At Christmas time, which was always the best time of year, people just didn’t buy anything. I realized then that the writing was on the wall. I’m glad I did because my real desire was to stay and hold on, but I never would have been able to.

I ended up owning an art gallery in Dumbo, which was three years old in the Fall of 2007 when the economy just collapsed. At Christmas time, which was always the best time of year, people just didn’t buy anything. I realized then that the writing was on the wall. I’m glad I did because my real desire was to stay and hold on, but I never would have been able to.

So I closed that gallery in February of 2008, and the Brooklyn Flea Market started in April in Fort Greene. I started selling and restoring clocks, and people started asking right away about watches, which I had no experience with at that time. So I sought out this guy [Steven D. Richardson] who has his own watch company [and non-profit watch school] here in Brooklyn, and learned from him the techniques of working with watches. The mechanics and the technology that makes them run is very similar to the way mantle clocks work, but the way you work with watches is different cause everything is so small.

So I learned from him and then about two years ago started this line of Brooklyn Watches. It started out kind of slowly. At that time I was selling vintage watches, like pocket watches and older wrist watches, as well, but the Brooklyn Watches part of the business just grew over time, to the point that I’m not really doing anything else. I like doing vintage pocket watches, but they’re a whole different thing. And I love clocks, but I’m kind of moving away from them as well because they are a lot more work and I don’t sell them for as much.

W&W: So how long was your apprenticeship?

DS: I studied with Stephen at the YMCA, in Bedford Stuyvesant. It was about a year that I worked with him all the time, learning about a variety of techniques and approaches. Then I started Brooklyn Watches.

DS: I studied with Stephen at the YMCA, in Bedford Stuyvesant. It was about a year that I worked with him all the time, learning about a variety of techniques and approaches. Then I started Brooklyn Watches.

W&W: You’re very focused on classic America timepieces, and vintage antiques. What’s your connection to that?

DS: I’m very interested in late nineteenth and early 20th century design, art and architecture, in lots of different ways, like technologies of clocks and typewriters, and aesthetics as well. So watches came very naturally. Actually, these dials were made in the 1960’s, but I think they refer to early 20th century American watches. And again, those watches were looking at early 19th century European watches, so things all get linked together.

As I mentioned, my training is in photography, and I was working for years and years in photography. I think that at least part of my approach to photography, especially now, it’s very technical. It is very involved in antique photo processes. So in that way there’s a relationship, like a sort of geeky scientist guy, mixing up chemistry vs making mechanical things go.

There’s also an aspect, and this is more with old clocks, of rescuing something. To want to find something that was important to someone that used to go, that now doesn’t go, or some process that people used to use that they don’t use anymore, to kind of keep those things alive.

W&W: We want to dig a bit deeper into the watches themselves. What drew you to the vintage Unitas pocket watch movements specifically?

Originally, it was because I was working with them when I was working with Stephen at Art of Horology. It’s a really great movement to work with when you’re learning. They’re kind of big. I think that lots of people learn on them. The thing that makes my watch line go is that while Unitas no longer exists, ETA continues to make the movements, so there are people still out there making dials and cases and hands to fit them.

I started buying vintage pocket watches because they were cheaper than the new movements. I kept buying them because I think they look better, which is important because all of my cases have display backs. They’re also available in a bunch of different finishes, colors and combinations.

I started buying vintage pocket watches because they were cheaper than the new movements. I kept buying them because I think they look better, which is important because all of my cases have display backs. They’re also available in a bunch of different finishes, colors and combinations.

Every once in a while I use a new movement. There are skeleton movements, movements that are cut so that you can see through them, and I really love them. I bought one and put it in a watch. They’re a lot more expensive, and I remember thinking “Oh, I’ve really gone out on this horrible limb. I’ve invested hundreds of dollars into this watch. It’s priced at $795. No one is going to buy it.” I sold it in two hours, to some guy who I never saw before. He came along and was like, “Wow, that’s great!”

W&W: What is the design process for a new Brooklyn Watch?

DS: With my training, when I went to school for photography, I was actually part of a graphic design program. I once designed and fabricated a bunch of dials from scratch, but I’ve sold them all and I haven’t made more. I worked with a guy at the flea who makes jewelry out of vinyl records, and he has a laser cutter, so I designed the dials in illustrator and he manufactured them. I think that’s the most creative aspect of designing, and I want to get back to it.

As an intermediate step, I’m thinking of doing some hand made dials. Either figuring out how to engrave them with an engraving tool or paint them by hand, which is how watch dials used to be made. Not really in the 20th century, but certainly in the19th. So I love the idea of being able to fabricate my own stuff but, most of my watches are more like collage work. It’s finding something vintage, or something new that I really like and then combining it.

As an intermediate step, I’m thinking of doing some hand made dials. Either figuring out how to engrave them with an engraving tool or paint them by hand, which is how watch dials used to be made. Not really in the 20th century, but certainly in the19th. So I love the idea of being able to fabricate my own stuff but, most of my watches are more like collage work. It’s finding something vintage, or something new that I really like and then combining it.

W&W: Are you looking to expand Brooklyn Watches?

It’s tricky. I’ve been thinking a lot about expansion, to some degree because making the watches is so time consuming. I used to make a watch a week, and then I was making two watches a week, and that was going really well. But selling two watches a week is not bringing in enough money to actually run the company. So in Spring 2011 I started selling about three a week, pretty regularly, but I started having trouble keeping up. So I’m not sure how much more I can do. Also, It’s not like I can call up a supplier and request twenty vintage pocket watch movements. It takes a long time to find the vintage movements I need, and that’s just part of the process of making my watches.

So the first place to cut time is the Flea. If I could hire someone to sell the watches for me, it would give me two days a week, which is a huge amount of time. But I really feel like its a big selling point that I’m standing there, as the guy who made the watch, talking to people. I think a lot of people really respond to that. I know a lot of people do, because they tell me so. So, I don’t see myself expanding into some big company. It would change a lot, and I don’t know how much I can actually do because of finding the vintage material.

So the first place to cut time is the Flea. If I could hire someone to sell the watches for me, it would give me two days a week, which is a huge amount of time. But I really feel like its a big selling point that I’m standing there, as the guy who made the watch, talking to people. I think a lot of people really respond to that. I know a lot of people do, because they tell me so. So, I don’t see myself expanding into some big company. It would change a lot, and I don’t know how much I can actually do because of finding the vintage material.

W&W: Your prices are very competitive, especially for a bespoke watch that uses vintage components. Is there a philosophy behind that? Are you looking to maintain that pricing?

DS: I think its what the Brooklyn market will bear. That $500, $600 or $700 price is what people are willing to spend here. It’s actually slightly above wholesale, and I’ve run into the problem where a number of people have wanted to carry my watches, but I can only give them 10% off the sale price. A watch that is $500, I unfortunately cannot sell it to a retailer for $250, which is what they’re expecting. They’re expecting my prices at the Flea to be retail, and they’re not. And that’s part of the way I’m staying competitive.

W&W: Your watches are all named for areas of Brooklyn. Does one inform the other? Is there a connection?

DS: I’m trying to make my watches like the neighborhoods they’re named for. The Williamsburg is kind cool and modern, but maybe not as cool and modern as the Bushwick. The Park slope is sort of sporty and the Brooklyn Heights is more fancy.

At first I couldn’t figure out what to call the line. My idea at first was just Brooklyn, but there was a company in the 19th Century that was called the Brooklyn Watch Company, and they often signed their dials “Brooklyn.” You know, Elgin and Waltham are named for the cities where the watches were made, so it would be right to label my watches Brooklyn. But because I’m mixing vintage and modern, I didn’t want anyone to think that it was the same company from 100 years ago.

W&W: Lastly, were you a watch geek before learning to make watches? Do you have a collection?

DS: I guess I’m a watch geek, but I can’t compete financially with people who have these astonishing collections. I used to wear vintage Elgins, and I have a beautiful Lord Elgin from about 1939 that was given to me as a gift. There were times when I would wear these to the flea. But I find that it doesn’t work very well to wear someone else’s watch when trying to sell your own. Customers will say, “Well, what are you wearing? Why aren’t you wearing your watch?” So now I don’t wear other watches anymore.

DS: I guess I’m a watch geek, but I can’t compete financially with people who have these astonishing collections. I used to wear vintage Elgins, and I have a beautiful Lord Elgin from about 1939 that was given to me as a gift. There were times when I would wear these to the flea. But I find that it doesn’t work very well to wear someone else’s watch when trying to sell your own. Customers will say, “Well, what are you wearing? Why aren’t you wearing your watch?” So now I don’t wear other watches anymore.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

You can find David and his watches at the Brooklyn Flea every Saturday and Sunday, and they can also be purchased through his website, brooklynwatches.com.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos