If Watchworld were a sensible place, a watch offering terrifying accuracy, with a tiny crystal heart beating at around 32,800Hz, that never needed winding and that would withstand all but the toughest of shocks would be held up as the pinnacle of watchmaking. If that wonderwatch could also be replicated millions of times for just a few pounds, there’d be temples built to it.

But Watchworld is about as sensible a place as Blefuscu. Instead of being lauded, watches like this are dismissed as “cheap” and “dull”. These same cheap and dull watches will barely drop a second a week and tell you the date perfectly for the next five hundred years – for less than £100.

But, slowly, digital watches are making a comeback. And here’s a bit of advice from someone who’s been around since before the first digis; get in there while you can. Those unloved old digis that languished forlornly in the charity shop bargain bin are making their way to serious watch auctions and dealers.

Go hunting for a vintage Patek at the local boot sale and you’ll come away empty handed. Go vintage digi hunting and you’re almost guaranteed to score – for pennies. It won’t last, so get out there while you can.

Where to start? OK – basics…

There are three types of vintage digi:

- LED – Light Emitting Diode. Press a button and the display lights up

- LCD – Liquid Crystal Display. Always on, usually black and white displays (although some of the early variants are green and black)

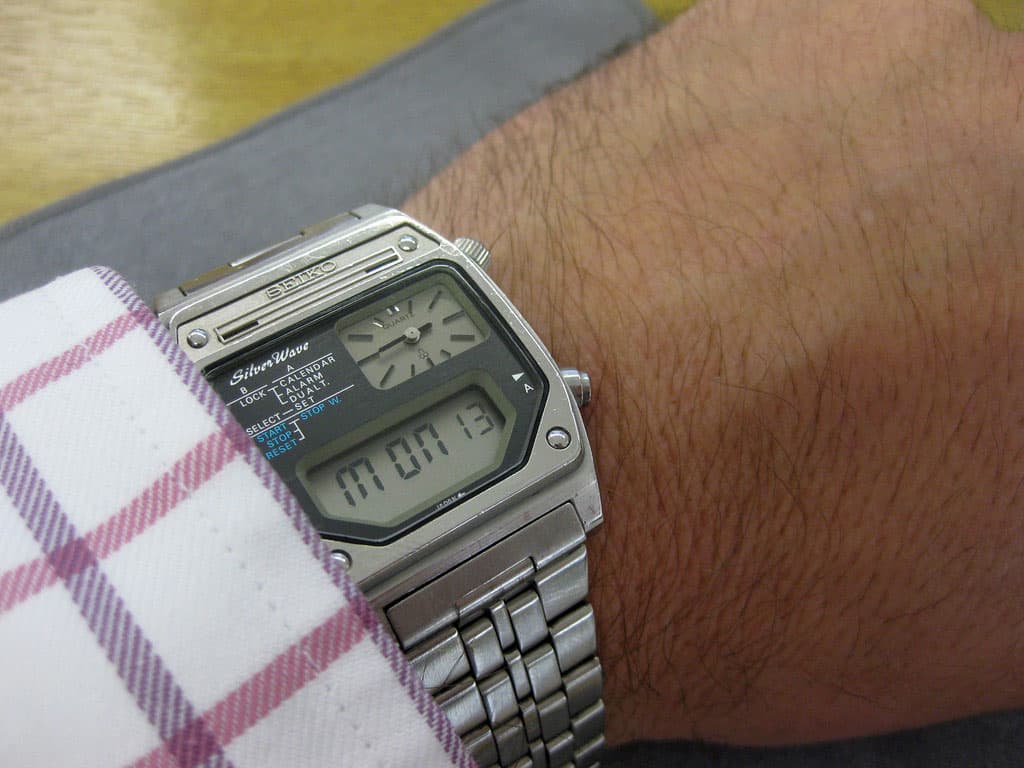

- LCD/analogue combo – a traditional, analogue face combined with a digital module.

We’ll ignore the exceptions to the rule, the Longines G-II and the 1978 Heuer Chronosplit that ran both LCD and LED modules in the same case. These are so daftly rare; if you find one – buy it (the Heuer will set you back around $5,500).

LED – time at the push of a button

LED led the way back in the early 1970s. Hamilton and Electro Data worked on an early prototype watch in 1970. This collaboration finally saw Pulsar releasing a production version of an LED watch in April 1972. Powered by two cells (not for very long – these things had a phagic appetite for batteries), the early LEDs told the time, date and would give you running seconds too, all at the push of a button. This, ladies and gentlemen, was the advent of the Pulsar P1, often claimed to be the first digital watch.

P1s ate through almost as many original modules as batteries (fortunately modern replacements are easy to find). The P2 gave a better showing, and to slip one on your wrist in 1973 would have cost you $395. Today, £400 would snare you one from a dealer. Or one could pop up in your local charity shop for £5 if you’re lucky. The joy of vintage digis.

The early Pulsars and the Omega Time Computers used a great deal of common technology, including a magnet in the clasp that the owner used to set the watch. There were two slots on the rear of the case, one for hours and one for minutes. You placed the magnet into the slot to reset the time. In fact, Omega shared Pulsar’s Time Computer module until the mid-late 1970s.

These were properly prestige watches. The P2 cost $10 more than a Rolex Sub, and Omega offered the Time Computer (TC) in 18ct gold. Sadly, the chances of picking one up today are slimmer than a Longines Feuille D’Or – most have been melted down for scrap long ago when the modules failed.

And LEDs weren’t restricted to basic timekeeping. If you spot a 1977 Hewlett-Packard HP-01 LED calculator watch, look to fork out at least $6,000 for a good one with box, papers and its all-important stylus. Spot a ’76 18ct gold Pulsar Time Computer/Calculator for anything under $25,000 and it’s a bargain.

Even Sinclair (remember the ZX81?) got in on the act in 1975 with their LED watch, designed by industrial designer John Pemberton. By this time, though, Texas Instruments were already driving down prices with plastic cased digitals. Again – because they were almost disposably cheap, they’re rare in good condition today.

LCDs, no need to push buttons

Almost at the same time as the power-hungry, glow-in-the-dark LED watches were being launched, LCD technology was starting to find its way into watch cases. If you’re looking for a practical, daily wearer, LCD is the way to go. Less power-hungry than LED and you don’t need to press a button to see the time.

Casio were straight into the market in 1974 with the Casiotron (¥65,000 to you, sir) that sired generation after generation of affordable, complicated LCDs. You can find Casio watches with calculators, TV remote controls, TVs themselves, altimeters, depth meters, watches that play tunes, games, call up demons from the pit of hell… If you were at school in the 1970s and early ’80s, you’ll remember comparing your watch to your pals’ to see whose had the most functions. The F-91W is still a classic today.

If you’re planning on a collection, the early Seiko M series LCDs are good place to start. They’re solid, easy to find, cheap on batteries and with plenty of spares around. There are enough good ones out there to walk away from the scuffed and bashed to pick up some 1970s cool for around £100 and only a few more pounds with original packaging.

Omega got in on the act with LCD with their cal.1620 that powered a series of new watches from the mid 1970s including the Constellation below. Like most vintage digis from serious brands, the movements are exceptionally well made. The cal.1620 even has a tiny circuit jumper to change the display from 12 to 24 hours. Yours today for around £500-£800.

There is an LCD Speedmaster too, the “Alaska IV”. That was based on the Speedmaster ST186.0004 with a cal. 1621 movement. NASA got 12 to test. The watches were used in training and on the Shuttle, but were never formally adopted. You’ll find one in Bienne – and another, No1 of the series of 12, surfaced recently on eBay where it was snaffled by a UK collector. If you spot an LCD Speedie, look for the writing on the dial next to the middle, right hand button. If it only has “split” next to the central pusher, it’s a NASA. The standard watches say “split, light”. That’s because the “Beta Light” used tritium tubes to illuminate the display.

Heuer were in there too, with the simple, tell-the-time LCD ref. 16061 right the way through to the rather more complicated ref. 105.703 models with a full stopwatch.

Combination LCD and analogue

Makers vied to out-do each other with complexity. This soon meant combination LCD and analogue watches. There were occasional forays into LED and analogue, Zenith’s Futur series for example, but most were LCD.

Omega got in first with their cal. 1611 Chrono-Quartz, the ‘Albatross’. Running at 32 KHz it featured a double LCD stopwatch display and a smaller analogue time display packed into its 51mm case. You’ll pay anywhere from £800 upwards today for the survivors of the original 15,000 production run.

Heuer weren’t far with their Manhattan Chronosplit GMT in its coffin-shaped case. If you find one of these with a working LCD module, it’s worth picking up. They’re tough to repair (although possible), and only very few makers are still carrying parts for the LCD. Look to pay around £1,500 for a working watch.

Far easier to pick up are ana-digi Citizens and Seikos. Citizen really took the whole ana-digi concept and made it their own. The JG200 series managed to pack in functions including temperature readings and dual times too. The JG200 series ran up until the early 2000s and even the laziest search of ebay will find you several good choices of watch.

So why collect vintage digis?

Unlike their mechanical cousins, you can track down historic vintage digitals without needing to part with a kidney. A cracking good example of the first significant LED can be yours for £800. But then there’s the Vintage Digi Random Factor (VDRF) to consider… yes, you could go to a dealer and stump up the cash, but you’re just as likely to find a grainy picture on ebay leading the way to your vintage digi dream.

Boot sales, junk shops, charity shops, house clearance sales – they’ll all turn up vintage digis. And that’s half the fun of them – history for pennies.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos