There is perhaps no other complication as popular as the chronograph. There is something wholly unique about a chronograph that makes it immediately appealing to both seasoned enthusiasts and casual consumers alike. Maybe it’s as simple as the aesthetics–the very nature of the complication lends itself to beautiful design. Or maybe it’s the fact that other than the date function, the chronograph may be one of the only truly useful horological complications. Sure, perpetual calendars and minute repeaters may enjoy a high level of admiration with the luxury crowd, but you’d be hard pressed to argue their usefulness in the day-to-day functionality of a watch.

For myself and for much of the worn&wound editorial staff, the chronograph’s intrinsic appeal stems from that very functionality. It is in many ways the ultimate expression of what we like to call the “tool watch,” and no other complication demands the same level of interaction from its owner the way a chronograph does. Unsurprisingly, its utility has been proven time and time again on the wrists of soldiers, pilots, race car drivers, and even astronauts.

In honor of the chronograph, we’re launching a multi-part series titled Chronography. With each entry, we’re going to explore a different facet of this well-loved complication, all the way from its history down to the technical nitty gritty. Today, we’ll begin with the former.

In 1816, a French watchmaker by the name of Louis Moinet created the Computeur de Tierces, the world’s first chronograph. It should be noted that Moinet’s invention is a relatively recent discovery (2013 to be precise), and for the longest time historians believed that Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec was the inventor of the chronograph. Regardless, Moinet was not only ahead of his peers, but his invention was also easily one hundred years ahead of its time. Resembling a modern stopwatch, the Computeur de Tierces was created with the purpose of tracking heavenly bodies. Much like a modern chronograph it featured two pushers, with one for starting and stopping the function and the other for resetting the mechanism. The central seconds hand measured 1/60th of a second, and the two sub-dials at 1 o’clock and 11 o’clock measured elapsed seconds and minutes, respectively. In a bit of a twist, the Computer de Tierces also ran at an astounding rate of 30 Hz (216,000 vph), a high-beat frequency that would not be seen again for nearly a century.

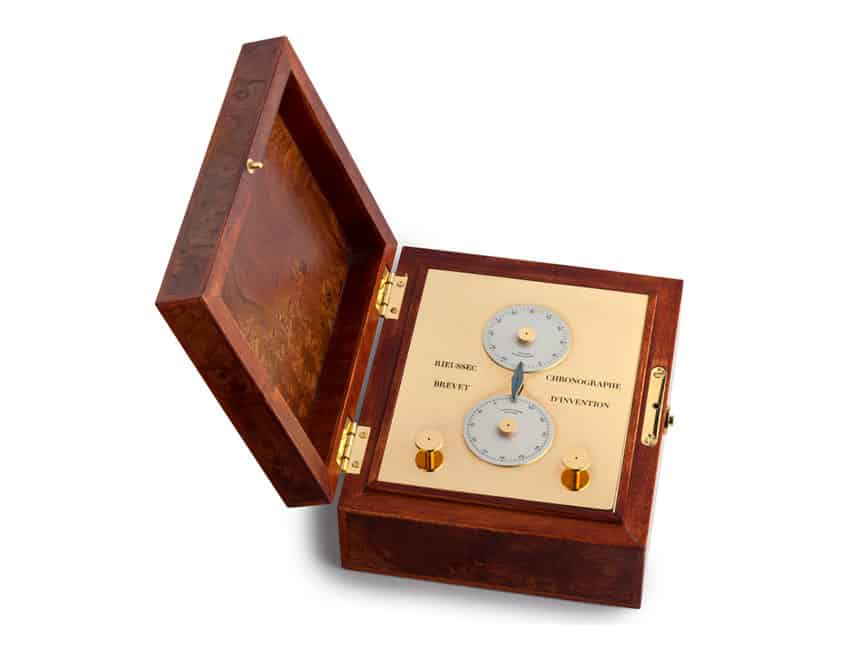

Despite the rewrite of history, Rieussec’s contribution to the development of the chronograph cannot be ignored. Created at the request of King Louis XVIII in 1821, Rieussec’s “ink chronograph’ was the first to hit the market. Its intended use was the timing of horse races, the King’s favorite pastime. The functionality of Rieussec’s chronograph was quite ingenious. When a race began, the chronograph would be set into motion with two rotating enamel disc–one measuring 60 elapsed seconds and the other measuring 30 elapsed minutes. When a horse crossed the finish line, the person operating the chronograph would press a button, which would drop an ink-filled nib onto the rotating disc marking the exact point in time the event occurred. These markings allowed the user to read the exact running time of each horse. Rieussec patented his invention, aptly naming it a chronograph–derived from the Greek words “chronos” (time) and “graphein” (to write).

At first, chronographs were placed inside pocketwatch cases and did nothing more than function as stopwatches. Unlike modern chronographs, they did not have an independent timekeeping function. In 1913, Longines arguably created the first chronograph wristwatch boasting an independent timekeeping function and a monopusher housed within the crown.

In 1915, Gaston Breitling created a wristwatch chronograph with a pusher independent of the crown. In 1923, Breitling furthered this idea by developing a system where a separate pusher (placed at 2 o’clock) would start/stop the chronograph, and the pusher within the crown would reset the mechanism. Finally, in 1934 Breitling took the next step toward the modern chronograph by adding a second independent pusher for resetting the function, an innovation that would soon be copied by all competitors.

In 1936, Longines created the venerable 13ZN caliber, the very first chronograph with a flyback function. That same year, Universal Genève created the first chronograph to feature a sub-dial measuring elapsed hours.

In 1957, Omega unveiled a watch that would become one of the most iconic chronographs of all time–the Omega Speedmaster Professional, aka the Moonwatch. The Speedmaster was first worn into space by astronaut Wally Schirra on his Mercury flight in 1962. NASA hadn’t certified the watch; in fact, it was Schirra’s own. But in 1965, NASA formally flight-qualified the Speedmaster for all manned space missions after it had passed a number of grueling tests under extreme conditions, with the Cal. 321 (a Lemania movement) beating out multiple chronographs from competing brands. The Speedmaster first saw official use in the Gemini program, but its claim to fame was Apollo 11, the spaceflight that took us to the moon. On July 21, 1969, the Speedmaster Professional cemented its place in horological history, worn on the wrist of Buzz Aldrin as he took his first steps on the surface of the moon.

Up until 1969, all chronographs out on the market featured hand-wound movements. The development of self-winding counterparts did not occur for a long time because the endeavor was deemed too complicated and firms saw no impetus for it. But with chronograph sales declining throughout the 60s, a few interested parties saw the opportunity to revitalize the complication. On one side, there was Zenith and Movado, who together created the Zenith El Primero. On the other side, there was the Calibre 11, developed by a super group consisting of Heuer, Breitling, Hamilton, Buren and Dubois-Depraz. And in Japan, there was Seiko quietly working away on the 6139-family of chronographs. Who made it to the finish line is a point of fierce debate, but historians generally give it to the Calibre 11 group for being the first to bring theirs to market in the summer of ’69. With that said, there are some who believe that Seiko really won the race, possibly hitting the Japanese market as early as May ’69 with watches produced some time in February or March of that same year. Regardless of who created the first automatic chronograph, the 6139 holds the honor of the being the first automatic chronograph movement in outer space.

In the early ’80s, Seiko made another significant contribution to the story of the chronograph. At the time, the Quartz Crisis was well under way, and battery powered watches were wreaking havoc on the Swiss. Being the innovators that they were, Seiko’s engineers decided that they would produce the world’s first analog quartz chronograph while everyone else was toying around with LCD displays. In 1983, they accomplished their goal with the release of the 7a28 movement. The 7a28 (and related movements) was incredibly sophisticated, and it was clear from the design and build quality that it was not intended to be a throwaway the way many modern quartz movements are. It featured full metal construction, 15 jewels, and separate motors (four in total) for each of the chronograph functions. If any part broke, Seiko intended for it to be repaired. The movement was so well received, in fact, that England’s Ministry of Defense issued their RAF pilots the 7A28-7120. You can read more about these watches here and here.

No historical overview of the chronograph would be complete without a look at what may be the most ubiquitous chronograph movement today–the Valjoux 7750. As far as automatic chronograph movements go, the 7750 was a relative latecomer, first arriving on the scene in 1974. But by 1975, the movement was all but dead. As previously mentioned, the Quartz Revolution (and Crisis) was pummeling the Swiss as consumers grew less interested in mechanical watches, much less so mechanical chronographs. Fighting to stay afloat, corporate ordered production to be stopped and for all tooling to be destroyed. Local managers thankfully ignored the orders and hide away dies–a move that would ultimately pay off a decade later. By 1985, the Swatch Group had been formed and conditions began to stabilize, and it was decided that the 7750 should be brought back from the dead. The 7750 quickly dominated the market with its robust build quality and attractive cost-benefit ratio. That combination kept many smaller firms, many of who were still on shaky ground, from investing in R&D to produce their own automatic chronograph movements.

Technically speaking, the Valjoux 7750 has gone through a number of significant changes since its inception. It began as a 17-jeweled movement beating at 21,600 vph, and today the jewel count has been bumped up to 25 and the beat rate is 28,800 vph. Unlike many of its contemporaries, the Valjoux 7750 did not feature a column wheel, but rather a coulisse-lever escapement–a feature that made the 7750 far more open to mass production (column wheels were and still are notoriously difficult to manufacture). For many brands, the 7750’s manageability and capacity for modification make it an ideal chronograph to play with, something that is quite evident with all the different variants on the market. Simply put, the 7750 is a workhorse, one that has long ago proven its reliability in watches both high and low.

With that said, the 7750’s reign may soon come to an end. With Swatch Group clamping down on third party sales, the 7750 may not be as common as it once was. It’s unclear who may step in and take its place, especially on the lower to mid-range section of the market. One promising alternative comes from Seiko in the form of the NE88, a chronograph that is comparable to the 7750 in size, function, and cost. Where it surpasses the 7750 is in its construction and design. The NE88 features a column wheel, a vertical clutch, and a triple-tipped hammer that simultaneously and instantly resets all sub-dial counters back to zero. Seiko sees major promise with the NE88, and they’ve recently been making a push to get this movement inside third party watches. And if anyone can produce the support and volume necessary to keep the automatic chronograph affordable and viable, it’s Seiko.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos