From time to time, we open Worn & Wound up to fellow enthusiasts, collectors, and niche specialists who want to write about a watch or subject we have yet to cover. Today, we’re featuring a guest post from Jarett Harkness, who’s going to tell us all about Hamilton’s important, and often underappreciated, foray into electric watches. And Jarret’s the right person to do just that. He began collecting and restoring Hamilton “Electric” watches in the 2000s, eventually training under the famed Rene Rondeau. Beginning in 2011, Jarett moved from working as a pharmacist to restoring Hamilton Electrics full time. When Rondeau retired in 2015, Jarett purchased the business and inventory, and today he operates his website, unwindintime.com, offering restoration of Hamilton Electrics for clients and sales of restored Hamilton Electrics, as well as other vintage watches.

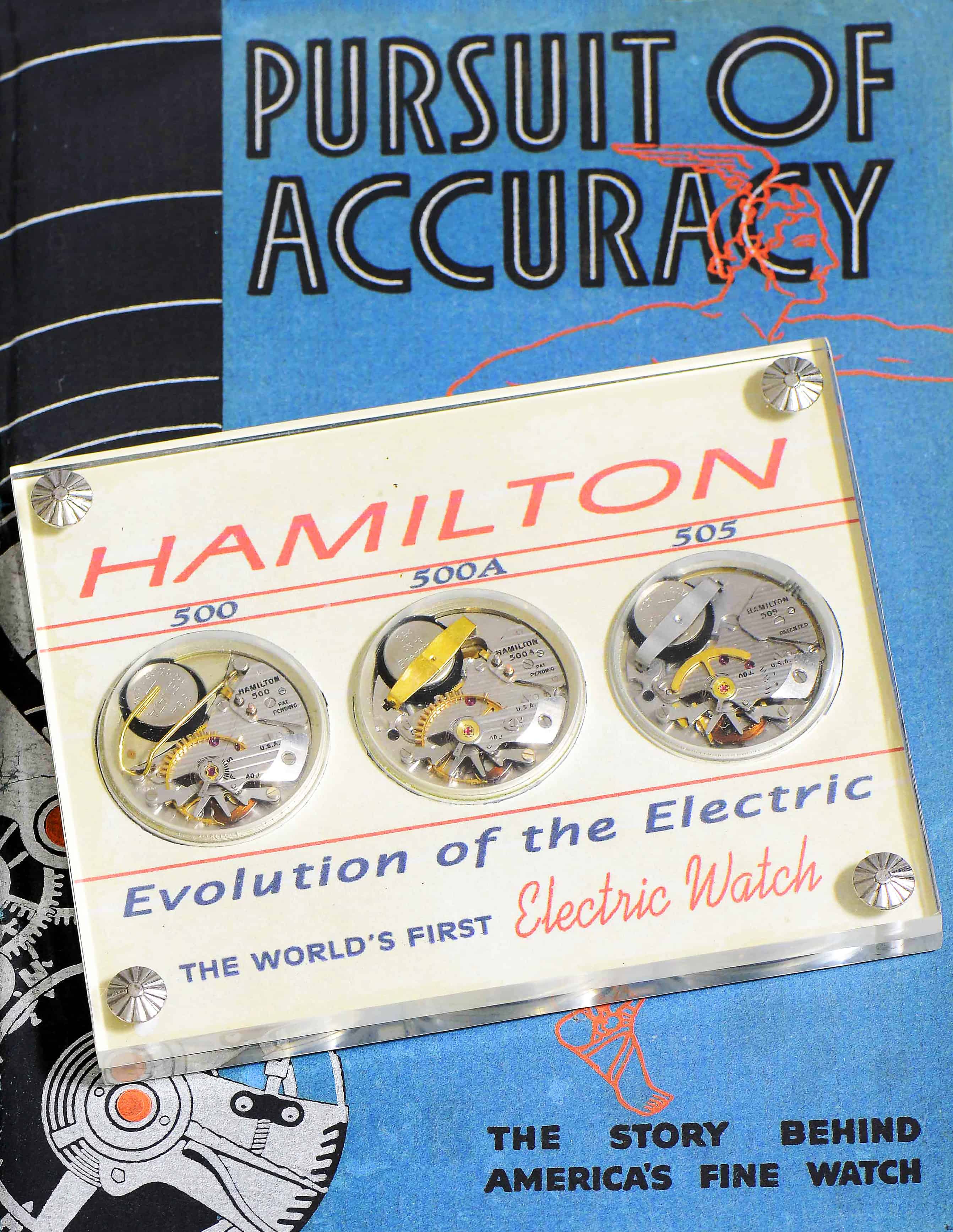

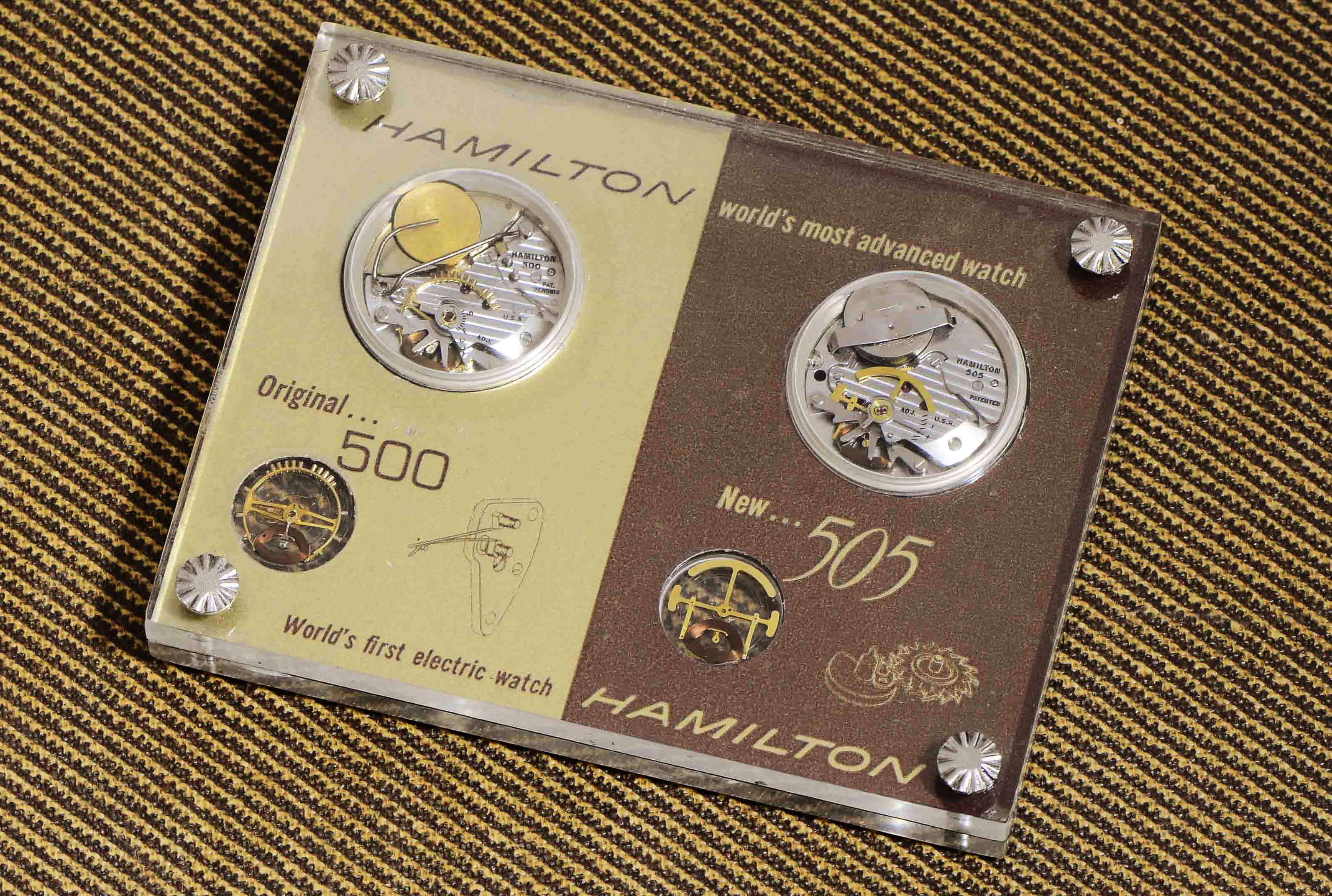

Hamilton Watch Company created a true icon with the 1957 introduction of the Hamilton Electric watch. It was the first significant innovation in mechanical design since the 16th century. Before 1957, all watches supplied power via a mainspring through either hand winding or kinetic energy (wrist motion with an automatic watch). The Hamilton Electric looked toward a different source, which resulted in a mechanical movement being powered by “an energy cell no larger than a shirt button,” as Hamilton once described it. Although the Hamilton Electric is powered by a battery, the operation is largely mechanical, using no transistors or other electronic components. It marks the first step toward the modern battery powered quartz revolution.

When it comes to the story of the Hamilton Electric, separating fact from fiction can be difficult, especially when some of these misconceptions have been circulating for sixty years. One pervasive misconception is that the watches never worked, or never worked well. And yet, countless examples can be found with original movements, and with watches used so extensively that holes have been worn completely through the cases. It takes years of continued use to cause this sort of wear, and, simply put, people were not strapping watches to their wrists every day unless they were running properly. Hamilton also produced approximately 350,000 Hamilton Electrics over a twelve year run. If these were duds, production would have been discontinued much sooner. Now, that’s not to say that there weren’t some reliability issues with early models (I’ll discuss that a little later), but it was Swiss competition and the coming quartz revolution that ended Hamilton’s Electric production, and not some inherent flaw in the product.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos