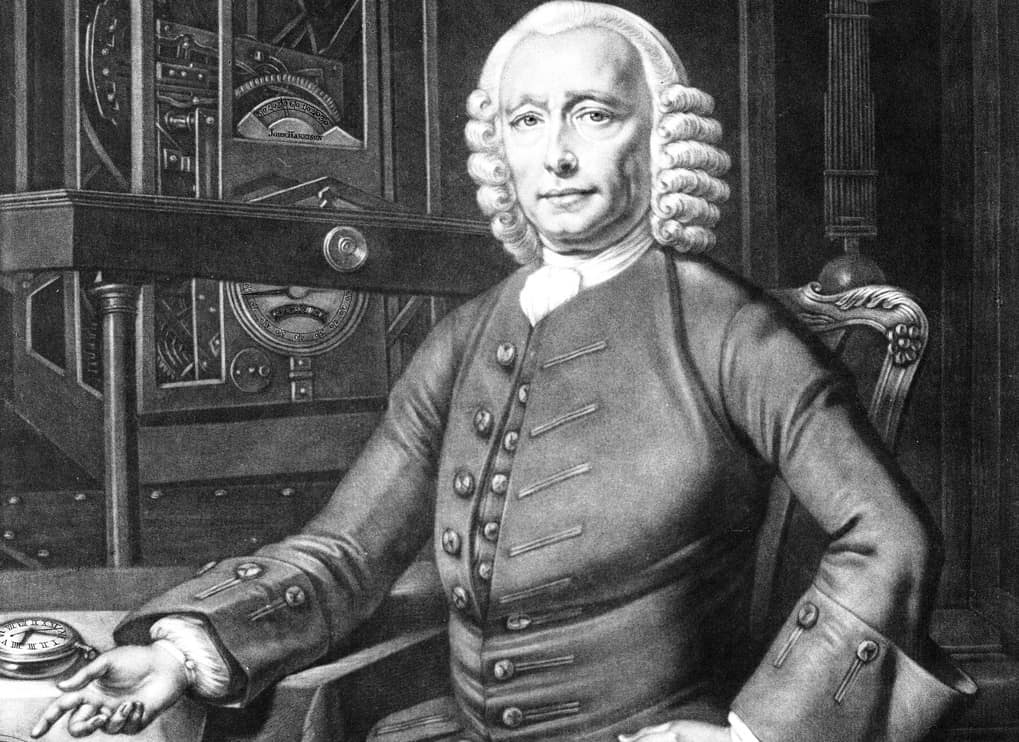

Enter John Harrison. In 1730, he was a self-taught clockmaker from Lincolnshire who had already made a name for himself by creating self-lubricating components for longcase clocks. Harrison had attracted quite a bit of attention in scientific circles, becoming fast friends with Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley (the man who calculated the orbit of Halley’s Comet). Halley campaigned for Harrison and his work relentlessly, introducing him to wealthy watch and instrument maker George Graham. Graham, impressed by Harrison’s initial Sea Clock design concepts, became a patron of his efforts and that year Harrison set about creating a design to take the Longitude Prize.

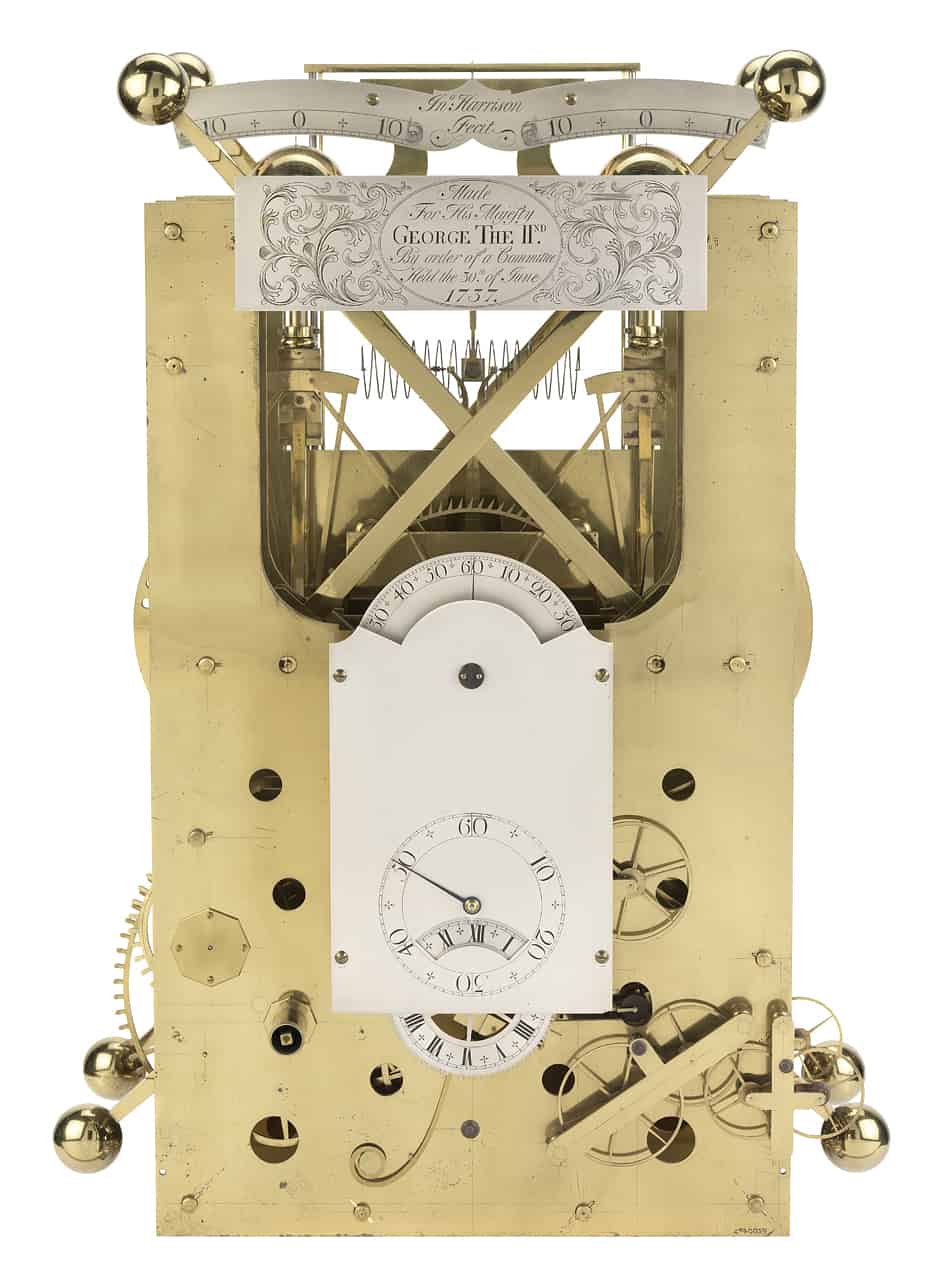

Harrison’s first attempt, the H1 Sea Clock, was an variation on his earlier pendulum clocks, modified to withstand the movement, salt air, and dramatic temperature changes of the open ocean. Featuring a pair of dumbbell balances to replace the original pendulum, along with wooden wheels, roller pinions and an unusual “grasshopper” escapement, the H1 took five years of assembly and on-land testing before Harrison was ready for a trial at sea. In late 1736, the Royal Board of Longitude approved Harrison’s design for sea testing, and sent Harrison and his clock to Lisbon, Portugal to rendezvous with HMS Orford for testing on the return trip to Britain. The experienced sailing master of the Orford, charting the voyage traditionally, miscalculated the ship’s point of landfall by 60 miles. Other crewmen, charting with the assistance of H1, accurately predicted Orford’s approach. Both the sailing master and the captain of the Orford were deeply impressed by Harrison’s clock, and recommended the design to the Board of Longitude. The board refused to grant Harrison the full £20,000 prize, as he did not fill the cross-Atlantic requirement, but issued him a £500 research grant to continue his work.

![HARRISON-H1]()

Harrison would spend the next 22 years gradually refining the sea clock. Two further iterations, H2 and H3, added ruggedness and more portability to the design, but the more Harrison refined it the more he realized the concept was fundamentally flawed. Although Harrison had fitted the H1 through H3 with massive balances to counteract the roll and yaw of the ocean, the balance of a clock vibrated too slowly to adequately stabilize timekeeping. He then turned his attention to miniaturizing the movement to speed up the vibration, moving from clocks to watches.

![John Harrison H2]()

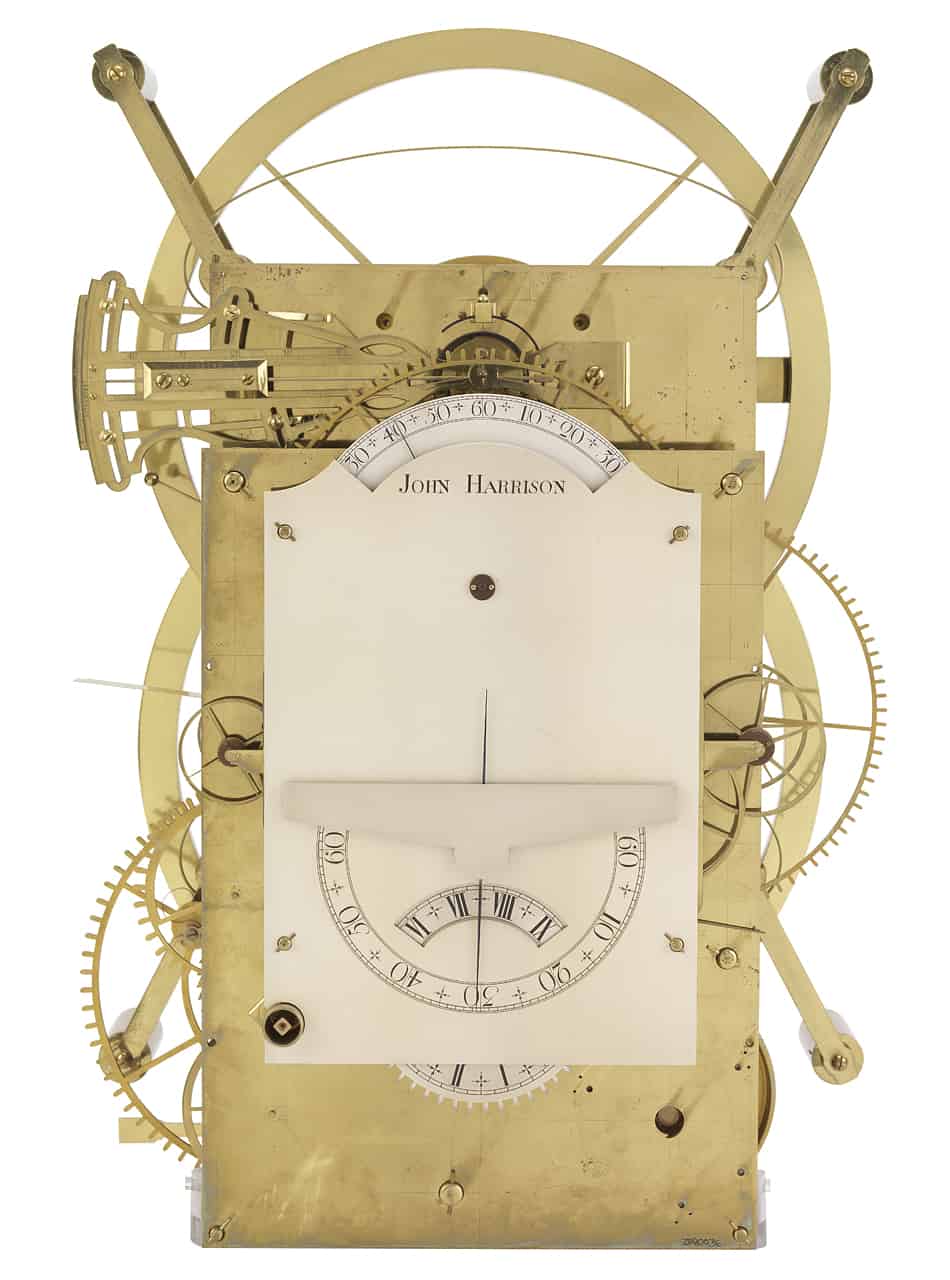

In 1755, he moved to London and began work on the H4, the first “sea watch”. The design featured a host of cutting-edge technologies, including an unusual vertical escapement with pallets made of diamond, an oversized balance with a flat spiral steel spring, advanced temperature compensation features, and a remontoire for additional accuracy. A remontoire, rarely seen in modern horology, was vital in those times for maximal precision. Essentially a smaller secondary mainspring near the escapement, the remontoire helped to equalize the drive force across the gear train, smoothing out power delivery.

All these advanced components took six years to construct, but by November 6, 1761 the H4 was finally ready for its transatlantic voyage. Harrison left the watch in the charge of his son William, who departed Portsmouth aboard the HMS Deptford bound for Jamaica. William’s charting, aided by the H4, correctly predicted landfall at Kingston within a margin of a single nautical mile- a stunning success.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos