Much has been written already about the world’s iconic military watches and their origins, with numerous articles on individual watches appearing over the years right here on Worn & Wound. In this series, we aim to do things a little differently by taking the reader on a world tour, stopping at a different country in each installment and discussing that particular nation’s military wristwatches, and for our first installment (released in two parts), we’re going to be covering the good ol’ U.S. of A.

World War I & Inter-War Years

America entered World War I in April of 1917, one year before the conflict ended, and it has been recorded that many doughboys arriving on the continent were in fact issued wristwatches. Though these watches were not given mil-spec markings like their counterparts issued to, say, the British Expeditionary Forces, certain models were produced specifically for military use and officially issued to U.S. soldiers.

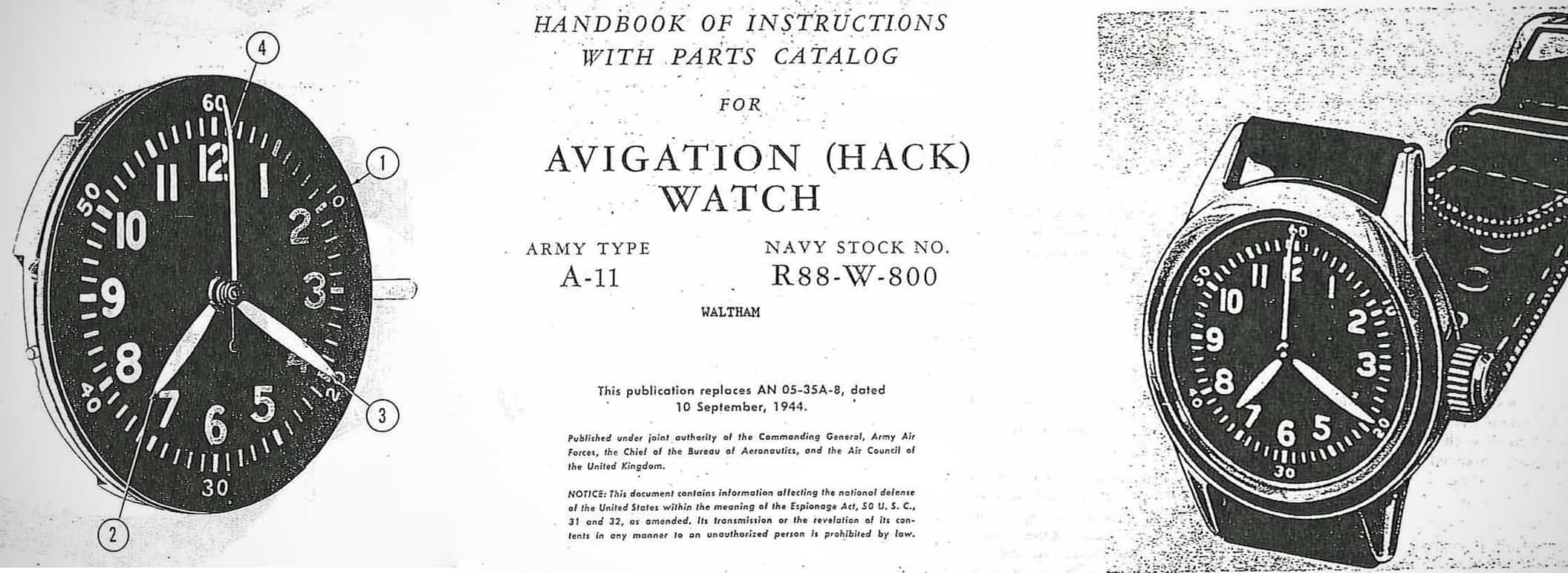

American watch manufacturing firms such as Waltham and Elgin produced watches for U.S. forces, and some were even given “ORD” (ordnance) markings upon being turned in for service after the war and later saw action during World War II. A War Department Technical Manual from 1942 even depicts these “trench watches” among its inventory.

The trench watch was essentially a transitional type of timepiece that saw soldiers trying to adapt the pocket watch for use on the wrist. At first, lugs were simply soldered on to an extant pocket watch and the timepiece was fitted with a leather strap. Eventually, however, recognizing the utility of a watch designed to be worn on the wrist to time artillery barrages, infantry charges, etc, the watchmaking community began designing and manufacturing them from scratch. Many issued trench watches featured a black enamel dial, radium-painted numbers and hands, a nickel or silver case, and an onion crown.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos