Editor’s Note: As we prepare to once again watch the ball drop in (a relatively empty) Times Square to ring in 2022, we’d like to take the opportunity to highlight the origins of that ball drop, as originally written by Ilya Ryvin back in 2017. From all of us here at Worn & Wound, we wish you and yours a happy and healthy New Year. Cheers.

Rewind: The Horological Origins of the New Year’s Ball Drop

Every year, millions of people tune in–or they actually make their way down to–the New Year’s ball drop at Times Square. It has been a New York tradition–nay, an American one–since the early 20th century, with revelers taking to the streets as early as 1904 to usher in the new year, and the first ball drop taking place just three years later in 1907. But the actual history of these “time balls” goes back even further, with their use going well beyond mere ceremony and celebration. In fact, unknown to most, time balls are a fascinating footnote in the longstanding tradition of public timekeeping. With New Year’s Day having just passed, we thought it would be interesting to take a closer look at these unique timekeepers.

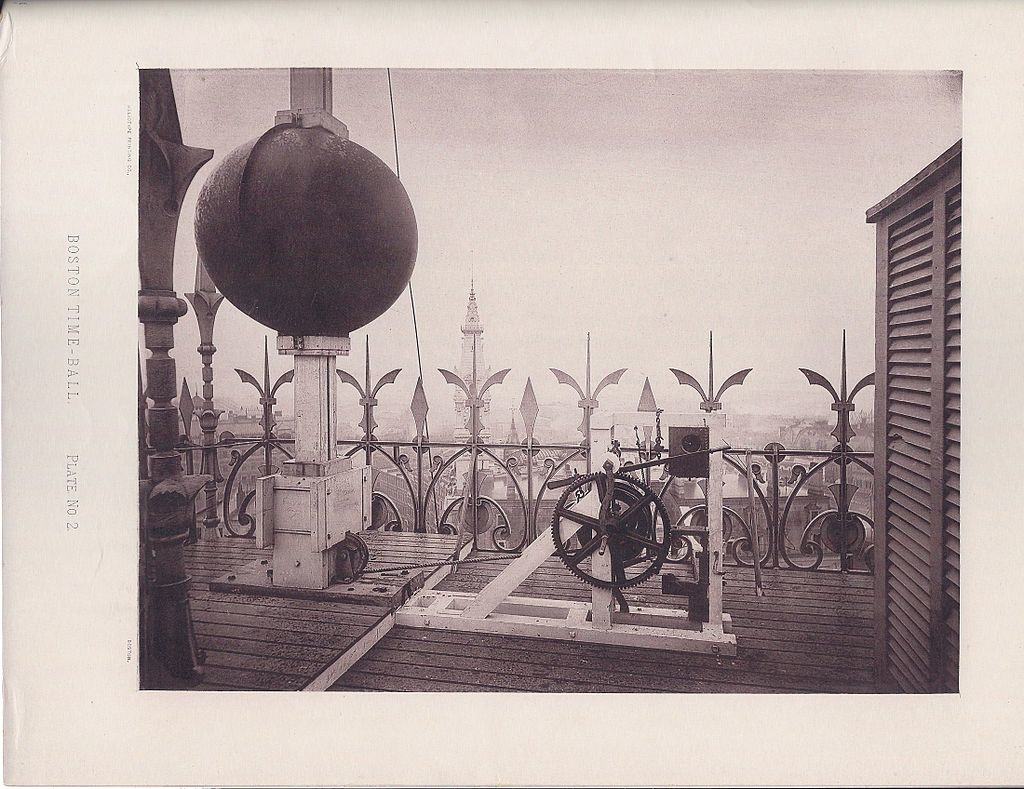

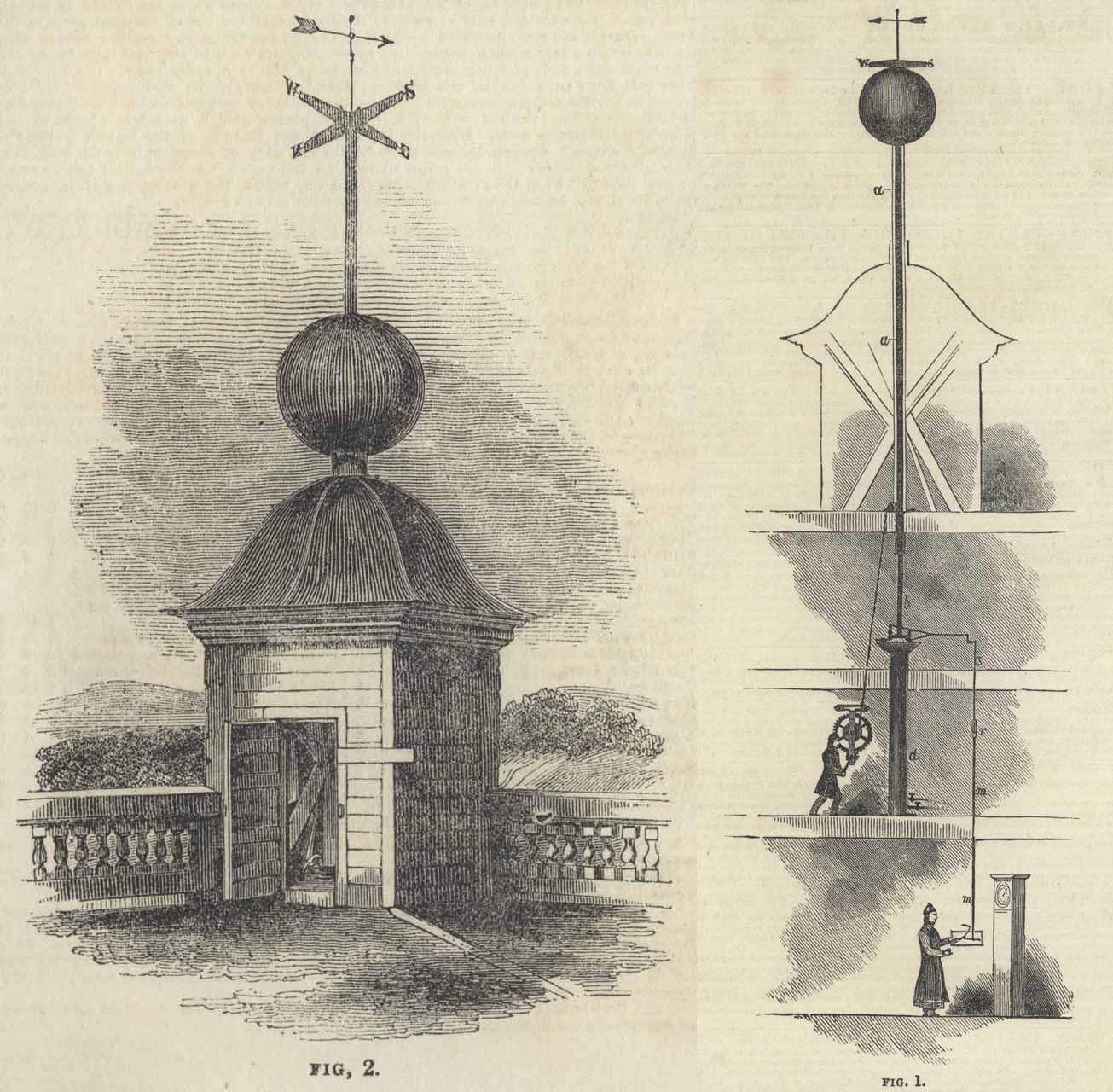

The first time balls were the brainchild of Royal Navy Captain Robert Wauchope. Remember, timekeeping was critical to seafaring, and before the advent of Harrison’s brilliant marine chronometer, accurate timekeeping was a huge problem. But even with the existence of chronometers, there were critical issues. These delicate devices would need periodic calibration, and doing so was often not a simple task, with sailors having to take them ashore to be properly synced. Wauchope’s idea offered a very simple solution. He proposed some sort of signal—positioned at a coastal naval observatory and large enough to be seen by sailors watching abroad their ships—that would indicate the exact time of day, every day. And thus, the first time ball was born in 1829, built in England’s Portsmouth harbor. A second was erected in 1833 at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. These early time balls were by no means ornate, often simply made of painted wood or metal and attached to a mast. By 1844, there were 11 such time balls around the world.

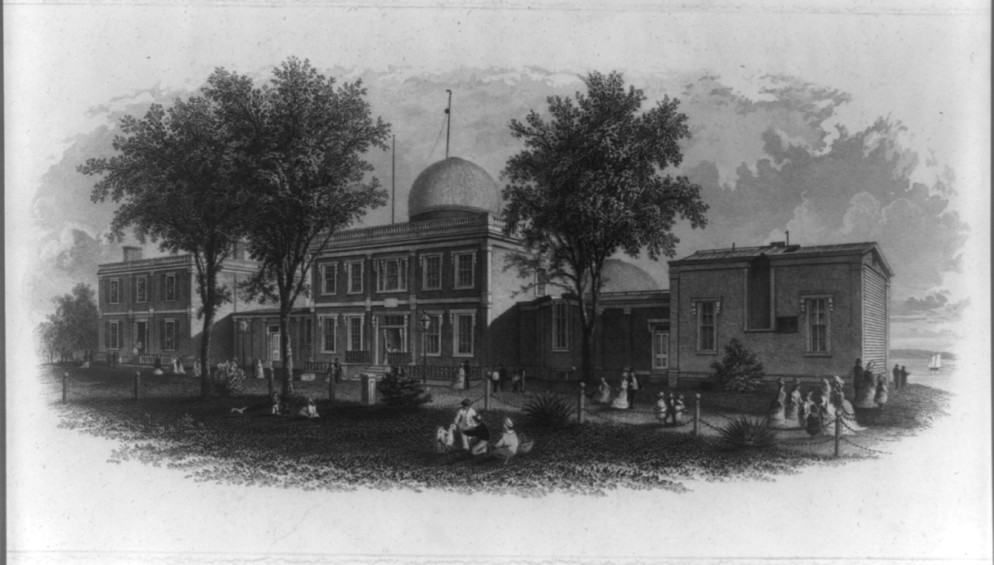

The United States Naval Observatory installed a time ball in Foggy Bottom, Washington D.C. in 1845, the first of its kind on our shores. The ball was made using a “Gumelastic composition” supplied by none other than Charles Goodyear. Unlike its British counterparts, it would drop at noon.

However, these simple machines were not without their problems. Marine chronometers were generally installed below deck, so those calibrating them often didn’t have a direct line of sight to the ball drop. Inclement weather conditions also meant potential for poor visibility and inaccuracy. And some have even argued that time balls were largely useless to navigators, who wouldn’t dock close enough to actually see the drop. And that time ball at Foggy Bottom? Well, that one eventually had to be thrown down by hand, where it would then roll along the dome of the observatory and onto the building’s roof. Legend has it former President Quincy Adams had a habit of walking by and watching the drop.

On land, time balls were far more popular, often pulling in large crowds to watch the drop. People also used them to set their personal timekeepers, as did nearby businesses. Eventually, more time balls appeared around the country on top of local businesses and municipal buildings. And here’s a little bit of trivia—we know that exact time of the fatal shot that killed Abraham Lincoln (10:13 PM) because the stage carpenter for the Ford Theater had synchronized the building’s clock that very morning.

As you may have already guessed, these devices are now obsolete, made so by the advent of radio time signals throughout the 1920s. Today, a few remain around the world as tourist attractions; the Greenwich time ball still drops every day. And of course, there’s the Times Square time ball—which is, rather ironically, initiated by an atomic clock, our current standard for timekeeping—reserved for that special occasion once a year where we all gather to watch.

Sources: New Yorker, New York Times

Featured Videos

Featured Videos