Today, watch lovers have multiple channels for discovery and research, among them (but not limited to) dedicated online magazines, Wikipedia, and a wide range of enthusiast forums. 20 years ago, however, this simply wasn’t the case. Rewind back to 1996. Text-based messaging systems like Usenet’s alt.horology and Prodigy’s message groups were being replaced by sites like Timezone. Also known as TZ, it attracted a large group of dot-commers, who at the time had an abundance of income and nowhere to spend it. Many of us wound up simply accumulating watches rather than pursuing the art of collecting. Moreover, there were very few authorities (the few included incredibly gifted writers like Carlos Perez and Walt Odets), but mostly there was just a lot of noise.

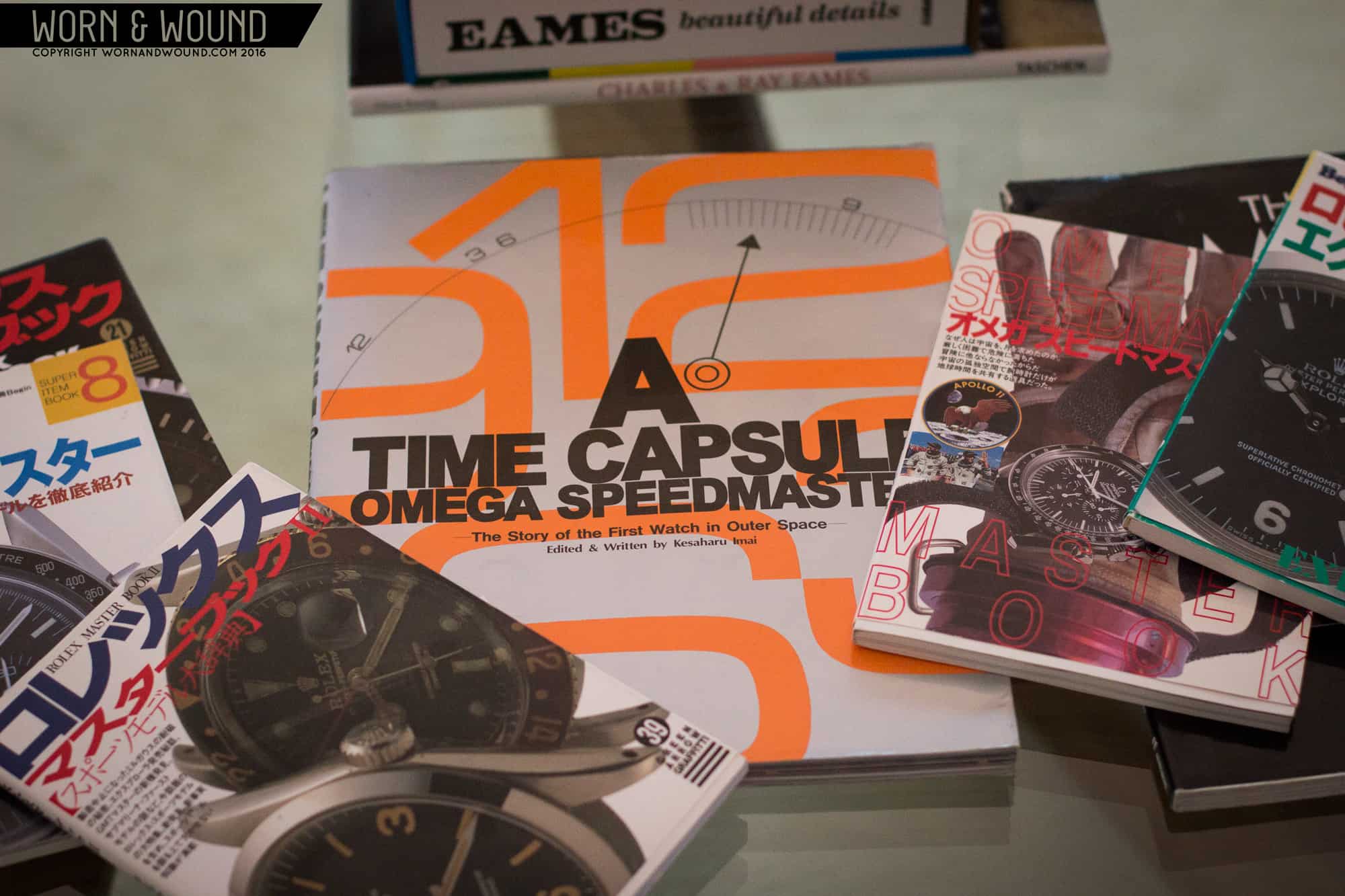

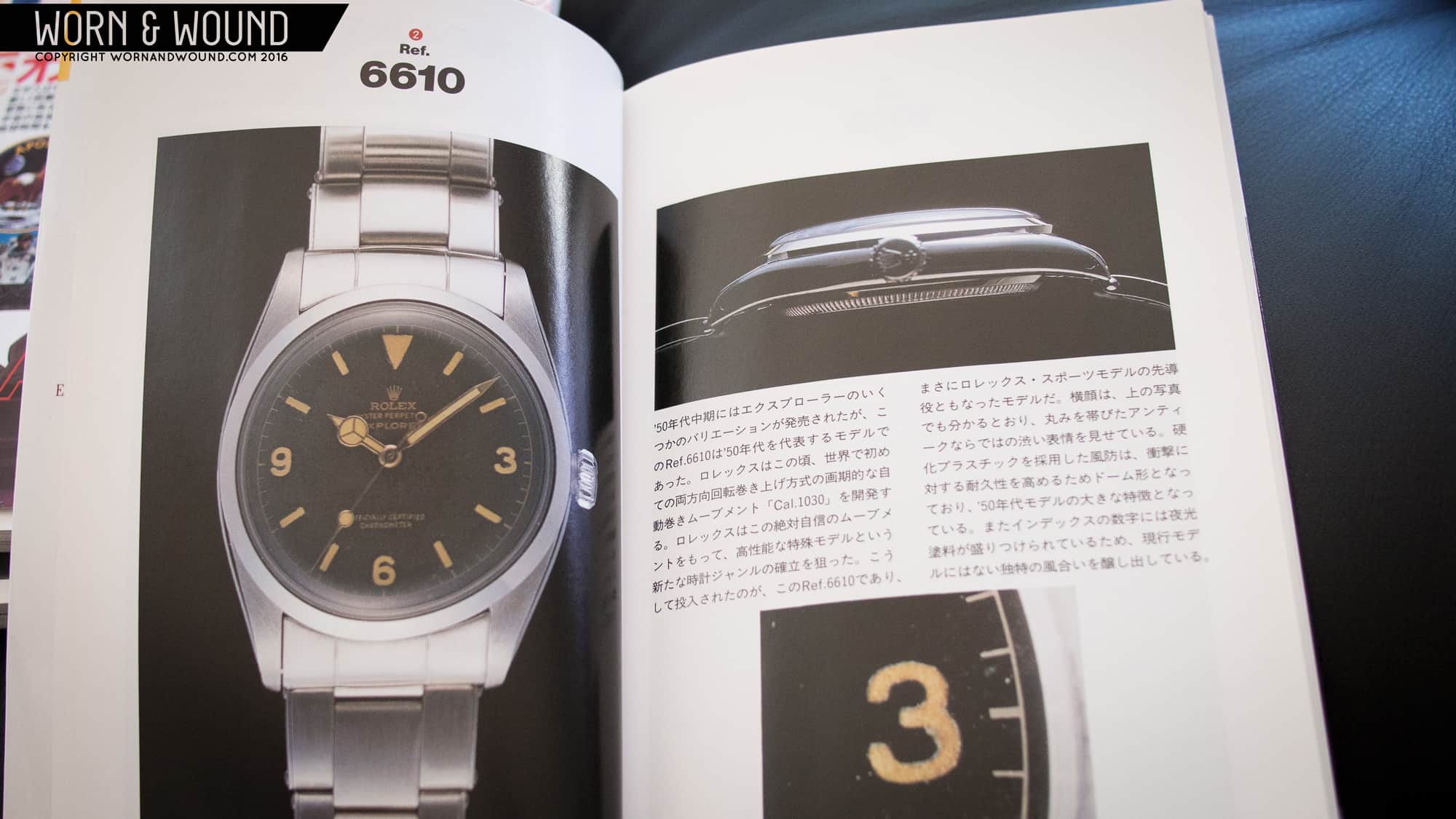

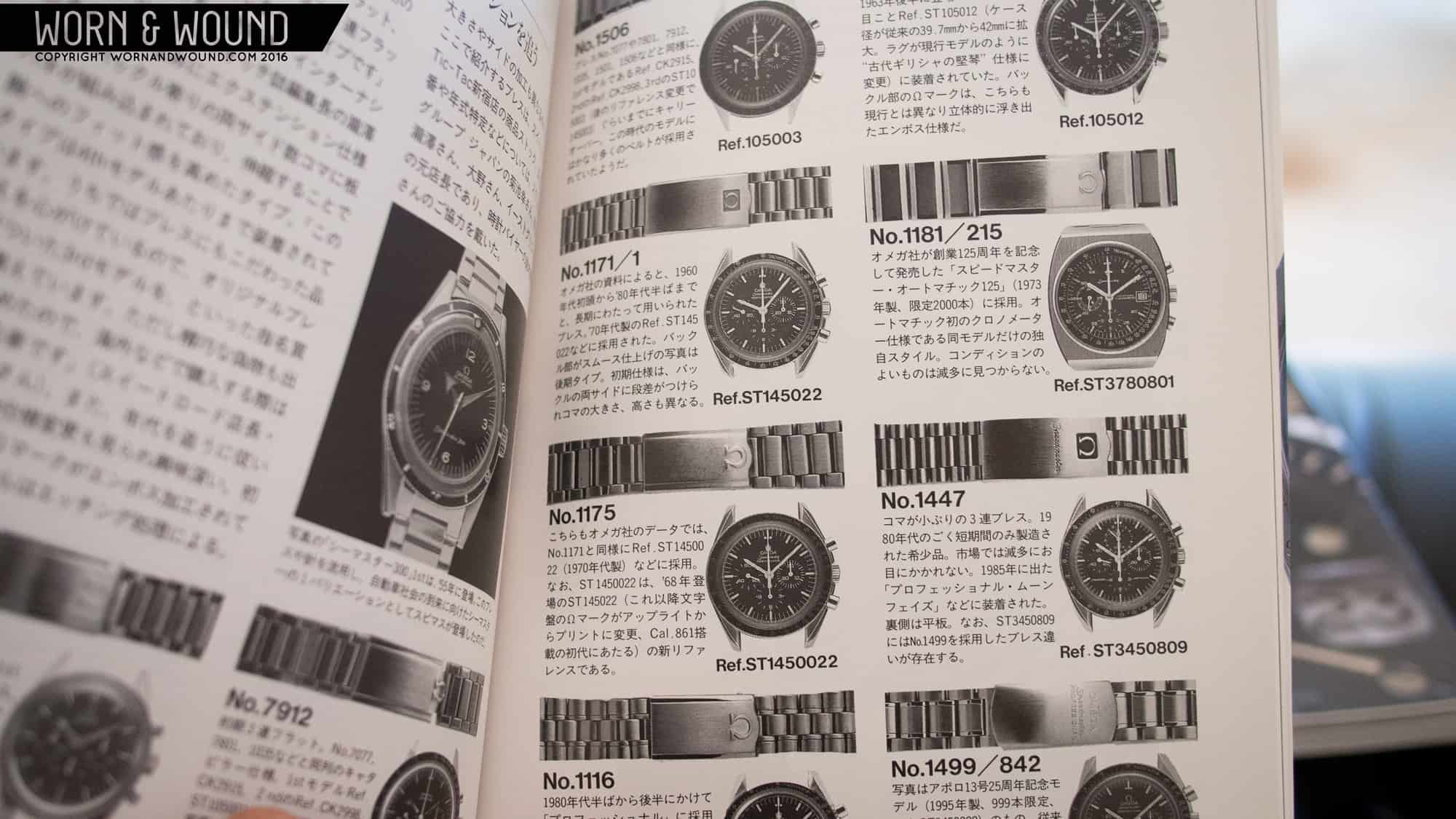

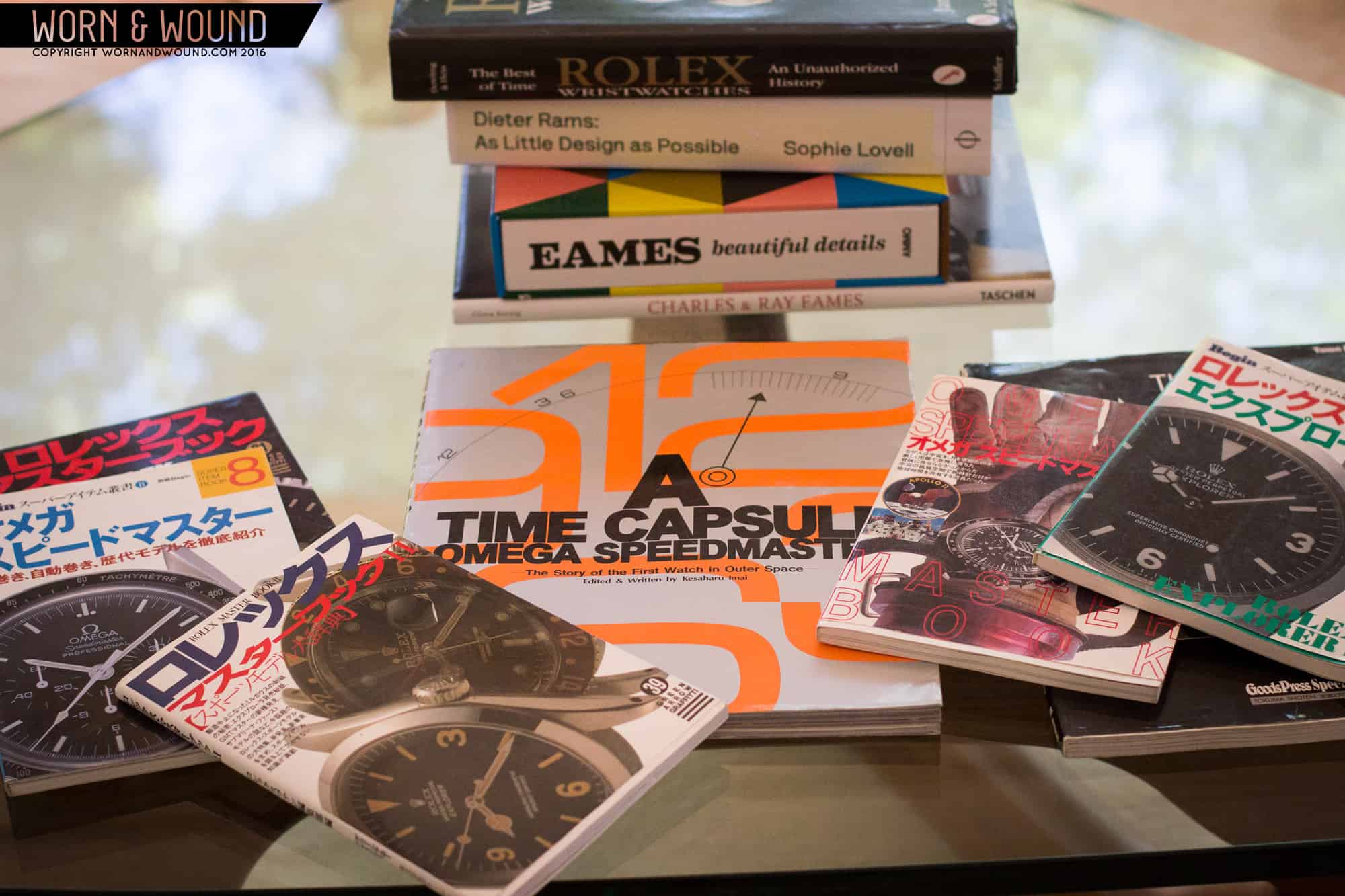

Due to this chasm in knowledge, dedicated collectors like myself still relied on books and magazines. But beyond James Dowling’s fantastic work on Rolex history, nothing else impressed me as much as what was coming out of Asia, specifically Japan. Simply, nobody else had the analytical depth and research compared to what the Japanese were doing, and I can thank a handful of Japanese authors for helping me incubate my thirst for watch knowledge. Strange enough, I discovered many of these books at a Taipei airport bookstore around 1998. Casually flipping through them between flights, I was quickly drawn into the details. I purchased the lot and took them home stateside.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos