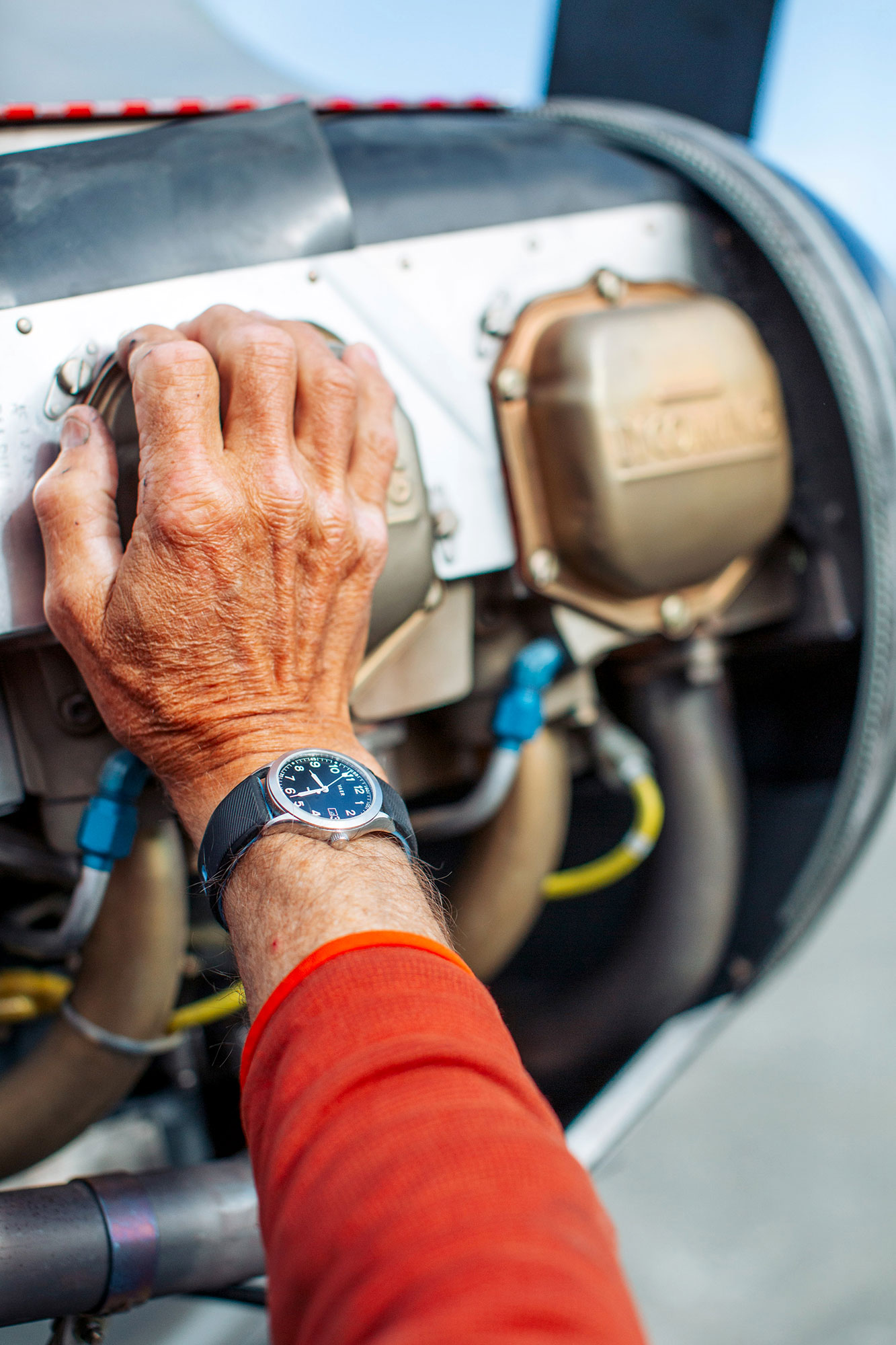

Every once in a while, you come across someone who can only be described as “The Real Deal” and we’re excited to tell you that Steve Davidson is just that. Steve is an Alaskan bush pilot and backcountry guide who spends his days flying around Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. He’s an avid outdoor enthusiast who grew up surfing and skiing and now takes adventurers, two at a time, deep into the Alaskan wilderness for wildlife spotting and backcountry skiing. Steve knows a thing or two about having the right kind of gear and he relies daily on his 36mm VAER S3 Calendar Field watch. For this final edition of Tool/Kit in 2023, Steve takes us through what it’s like to rely on a watch as a mission critical piece of gear for his life of flying in the bush.

Hey Steve. Thanks so much for speaking with us! Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and where you’re from?

I grew up in San Diego, California through high school. My dad was a big-time outdoorsman, loved to ski and fish. We had a cabin that he built in the Mammoth Mountain region back in the 1960s. I spent my childhood skiing up there. My dad taught me to love the outdoors since I was a little guy. I’ve always loved the outdoors. Basically the day I graduated from high school, I moved to Aspen, Colorado. I wanted to be a ski bum. Even though my dad was a surgeon, he never pushed me to go to school and when I’d come home he’d always proudly introduce me, “This is my son Steve, he’s a ski bum.” He just thought it was awesome. And I’ve always loved my family for being in support of my outdoor lifestyle.

How did you get your start in aviation?

I finally went back to San Diego for a couple of years, and went to a college that had an aviation department. So I learned to fly and to be a mechanic. I got married and worked for the airlines as a mechanic for a little while and then we moved to western Montana and that’s where my wife and I raised our kids. I was involved in an air tanker operation fighting forest fires until I started my own air charter business mainly focused on bush flying. I flew for all the hunting outfitters there and did wolf and elk surveying for the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission. I did this for a while until one night at a dinner party where I met the owner of Ultima Thule Lodge located up in Alaska within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. We hit it off. He invited me up to go skiing with him, so I came up here and went skiing. That was 14 years ago and I’ve never left.

What model and year airplane do you typically fly there out at the lodge? What are some key factors that go into making a bush plane?

Well, I’ve been flying for 38 years, so I’ve seen it all. At Ultima Thule Lodge, we operate Dehavilland DHC3 Turbine Otter, Cessna 185, and Piper Super Cubs. The Cubs do most of the adventure flying, but all of them are considered bush planes. All of them were built in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. They are all tailwheel airplanes, which means the third wheel is in the rear instead of the nose. This is a stronger design for off-airport operations, and really important for us during ski operation. The power to weight with all these planes is really great—lots of horsepower and a light airframe—this allows the plane to take off in short distances. They’ve all been legally modified for Alaska flying, some of these mods include: bigger engines, heavy-duty landing gear, large bush tires, etc., etc., etc. It’s endless. You can’t purchase any of these planes new, so we just keep rebuilding and maintaining them. There are very few new bush planes being built today that can be used for commercial flying. Also we feel the older designs are the best and proven here in Alaska. If it’s a bush plane, a piece of clothing, or a wrist watch—life in Alaska just seems to put things to the test.

What are the most frequent kinds of trips that you make, and what’s your favorite kind of excursion?

In the summertime, I fly a Super Cub every day. If you were to stay at Ultima Thule Lodge, you’d wake up and meet me in the morning and we’d just take off to wherever the weather looks good. I’m your pilot, but I’m also your wilderness guide. We might go to the beach and watch glaciers calve off into the ocean or we might go off for a big hike into the high alpine, have a great lunch, and then go back to the lodge for a 5 star dinner. One of my favorite things, and that’s what I’m doing now, is getting all our planes ready for our ski season. We do about 8 weeks of daily skiing runs in the spring and I really love flying Cubs on skis.

What’s one of the stickiest situations you’ve found yourself in?

Bear spray doesn’t really work so well where we go. So all the pilot guides carry a firearm. I carry a .44 magnum in a chest holster, which I rarely—if ever—have to use. However, last summer I came close—which again is an extreme rarity. I was out with some guests and we’d gone up this huge open slope that sort of reminds you of The Sound of Music. I knew this area was loaded with blue berries, so I’m watching for bears. The two guests are doing what they’re supposed to be doing, they’re following and I’m up ahead by about 10 feet. Then the guy says, “Hey, a bear!” I’m looking and I don’t see anything and then he says, “Behind us!” I turn and this bear, he’s comin’ like a freight train… I mean, full speed charge. I’m looking at his distance versus speed and I’m doing the calculation and realizing in my mind that he’s gonna be on top of us before I can get my gun out. And I think… oh my gosh, this is it. Suddenly he skids to a stop about 20 feet away from us.

He was upwind of us and bears don’t see very well, but they can smell anything. So with him being upwind, he’s coming at us to see what the heck we are. So there he is, stopped just short of us, and he stands up and this is an 8 foot tall grizzly bear. He starts making this woofing sound and sniffing the air. I had time to get my gun out. My guests were great, they stayed right behind me and they raised their arms up and we’re all yelling at him. “Hey bear! Go away, bear!” It kind of freaked him out and he dropped down, turned around and walked away. After he walked away, I didn’t let my guests know, but my knees were a little weak. But luckily, we got to go home at the end of the day and tell everyone about our bear encounter.

So you wear a Vaer field watch. How did you come across the brand and what do you look for when you’re choosing a watch?

I was in need of a new watch, so I started googling “watch reviews” or something like that and this Vaer turns up. They’re a U.S. company, they assemble their watches in the U.S., and I like that. I’m kind of an old school guy and I’d like to see more things manufactured here. I’ve had Suntos and these big barometer and altimeter watches. But I saw that Vaer makes this very small 36mm, low profile watch. I thought, “Wow! That looks great!” So I bought it without knowing much else. I just liked what they were sellin’. It’s worked out just great. In Alaska, I’m always wearing a Patagonia R1 hoodie. I always have long sleeves on and a big watch gets caught on a sleeve or you can’t button a sleeve. So it’s nice having this low profile, small watch that just slips under a sleeve. I’ve learned I don’t need a giant watch with all the bells and whistles, all I need it to have is a very legible minute hand and second hand. I set the Vaer’s time around Daylight Savings and since then, it’s always within seconds of where it’s supposed to be. It’s really been a solid watch.

Why is it important for a bush pilot to wear a watch?

There’s different reasons why you need a watch as a pilot. First, any pilot who knows what they’re doing is going to track their flight time, because the airplane is just traveling along in an air mass. But if that air mass is moving 30 MPH in the wrong direction, then the airplane—which is still going 100 MPH through the air—is only going 70 MPH across the ground. So your distance is much shorter on a tank of gas. Or you could have a 30 MPH tailwind, which means you’re now doing 130 MPH. So we always time our fuel with a watch. So you know that you’ve got a solid 3 hours of flight time, plus an hour reserve. The watch is super critical for that and every pilot should be tracking that.

Nowadays, with more modern GPS instruments you don’t run into this situation as much as you did when I was a young pilot. But when you’re instrument flying, your watch is incredibly important. If you’re totally flying on the gauges, which means you’re in the clouds; and then if your directional gyro system fails, all you have is your compass and your watch. A basic compass is terribly inaccurate, it has a lead and a lag and just bounces around. So in these conditions, if you need to make a 90 degree turn, you can make what is called a “Standard Rate Turn.” I know if I can stay in that turn at a standard rate for 15 seconds—just staring at that seconds hand—I’m making a 90 degree turn. It’s all based around speed, distance, and… of course, time.

When I was taught to fly they wouldn’t let you use navigational aids, so your watch was always being used. I mean always. So even with GPS—which can quit on you—when I’m going some place new I always have my watch and a map out. There’s pilots, and then there’s aviators. An aviator knows everything about that airplane, what systems do what, and if something quits… what hazards that might cause. An aviator knows how to read a map and how to do the time, speed, and distance calculations. Whereas a pilot can fly the plane really well, but may know nothing about what’s under the hood or how to not to rely too much on these new GPS ‘glass panels.’

Can you share with us some of your other mission critical pieces of kit, whether it’s sunglasses, apparel, or gadgets?

You can’t go anywhere without sunglasses. The Wrangell-St. Elias National Park is the most glaciated non-polar area on the planet. Even in the summer, we’re always flying on snow and it’s just bright as all get-out. I wear prescription glasses and there’s a company in Colorado called Opticus that specializes in making prescription glacier glasses. They have real dark lenses with side shields and they’re just really good glasses for what we do out here. And then I always have a sleeping bag, stove, food, first aid kit, tarp or light-weight tent. We always carry sat phones and DeLorme trackers. It takes a little bit of the wilderness out of it, but if something goes wrong, at least you’re not building a cabin for next winter.

Is there a particular flight you hope to make one day? Perhaps a challenging one you haven’t had the chance to do just yet?

Alaska is a huge huge place, so there’s still a lot of it I’d love to explore. But, and this will never probably occur in my lifetime, I’d also love to be a pilot for a float plane operation in like the South Pacific or the Bahamas or something. Just to try it out.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos