Back in the ancient past, when I first worked as a copywriter, we wrote on Mac Classics. If you were senior enough, you got a color screen. If not — and we were doing words after all — black and white was good enough for you, sonny. My Classic had a carrying handle tucked away on its top, so you could pick it up and take it with you. In my case, to the pub.

At the time, I thought this was cool beyond words, but I had no idea it was a feature if not borrowed, then certainly influenced by, designer, architect and creative Ettore Sottsass. His 1969 landmark Olivetti Valentine portable typewriter — co-designed with Englishman Perry King — featured a fold-out handle that also encouraged you to take your words with you.

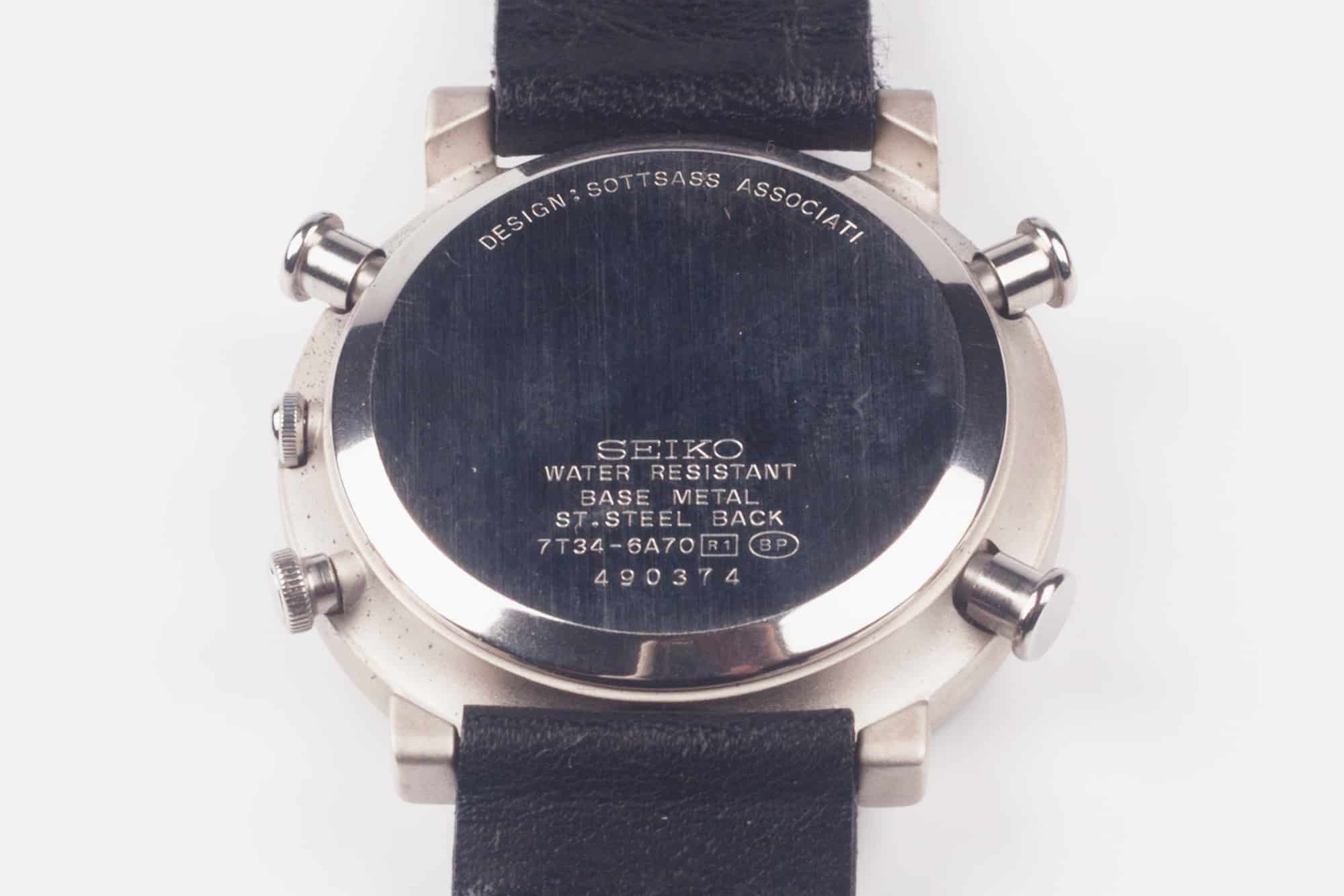

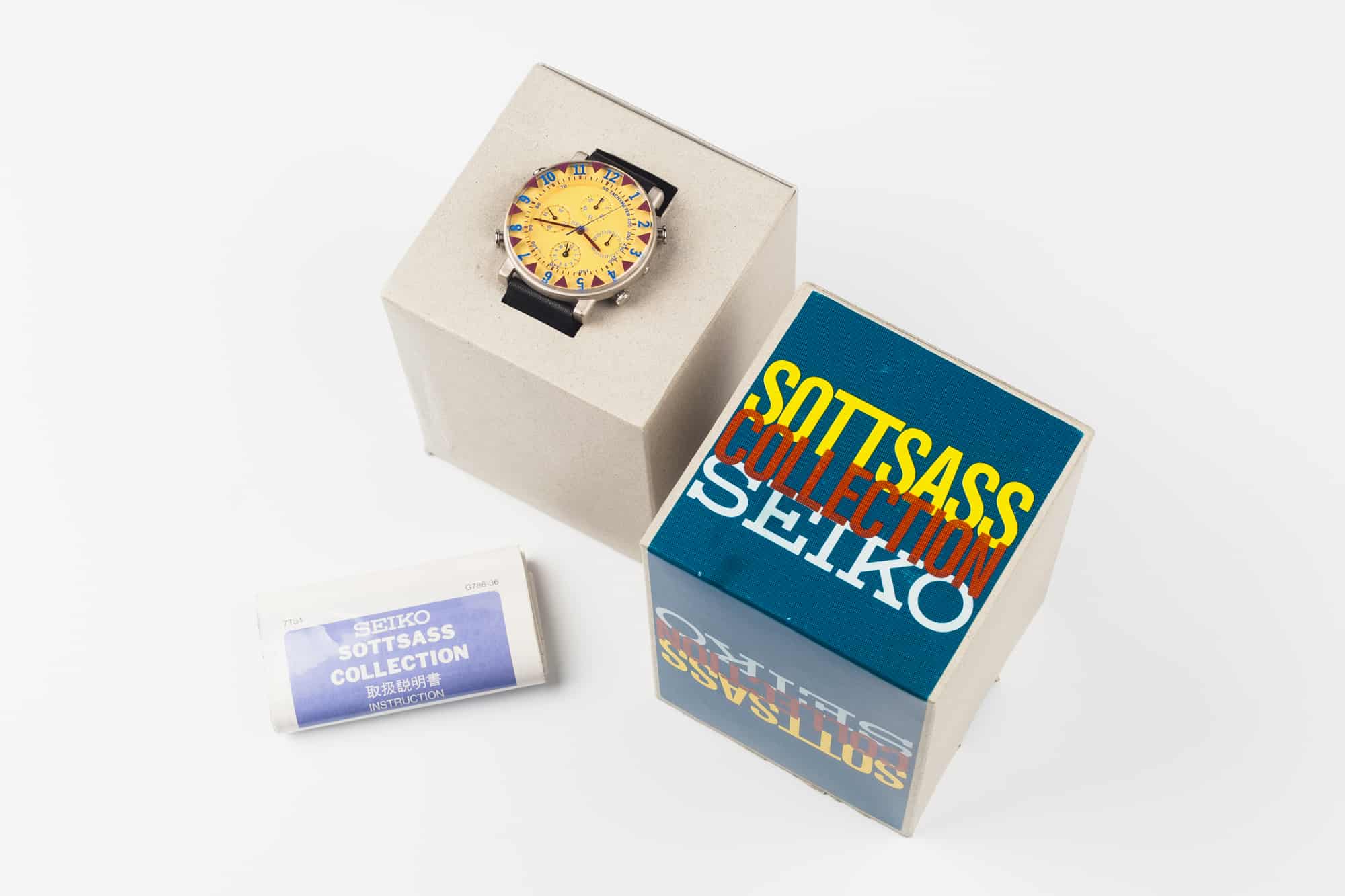

As well as typewriters, Sottsass (a member of the Memphis Group of designers) worked on architectural designs, industrial designs, and, in the early ’90s, turned his attention to watches. In 1992, he collaborated with Seiko on the logically, if unimaginatively-named Sottsass Collection.

Today, Sottsass’ watch designs aren’t perhaps as well-known as they should be, so it’s hats off to Chicago-based online design shop Philolux (see what they did there?) running the Postmodern Times exhibition of some of the Memphis Group’s watch and clock designs — including Sottsass’.

It’s worth talking a little about rarity at this point. For example, the new Rolex Daytona ceramic is rare. People are putting their newborn children’s names down in the hope they’ll get a watch before they get a pension. But these Sottsass watches are in a different league of rarity. You’re more likely to see a unicorn driving down Park Avenue in a pink 4.5 litre Birkin Bentley than see a collection like this in one place. Heck, one of these eleven (yes, eleven!) original first editions on its own would be rare enough, but the team at Philolux has been in close contact with a Japanese collector for the last couple of years, and he’s finally decided to sell his entire collection. Oh, and they come with their original boxes and instruction leaflets.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos