It’s a hot, muggy Saturday afternoon, and as a parent you find yourself at a local splash pad for a 3-year-old’s birthday party with 37 other people. Most of them are adults you don’t know, or you do know but have definitely forgotten their names.

After your kid finally sheds the shy cling to your leg and runs off to the water features with their buddies, you begrudgingly gravitate toward a few unidentified parents talking. Upon entering the circle, you present your name and state whose parent you are before an awkward silence falls, and you hear those words:

“So, what do you do for work?”

Because at this point it’s either that or the weather, and the circle has already covered the later topic one too many times.

Work—it’s that inevitable question we’re all asked during those awkward, seemingly weekly toddler birthday parties.

“I’m an Industrial Designer” isn’t the most glamorous or self-explanatory response.

That’s ok though, because after a few back and forth questions and answers in the circle many start to realize how much around them is designed, considered, and produced to make our lives a bit better. But like all coins, there are always two sides to the story. Making more things is not necessarily the answer, but I believe making things that speak to us, move us, and change our lives even in the slightest is what makes good industrial design great.

At its core, Industrial Design is the process of creating physical products for mass manufacture that people interact with in their daily lives.

Quick side note: “Product Design” used to be a great term for Industrial Design until UI/UX designers adopted it. After all, physical products existed long before coding, silicon chips, and software. But I digress—that’s a grudge only an Industrial Designer has to bear!

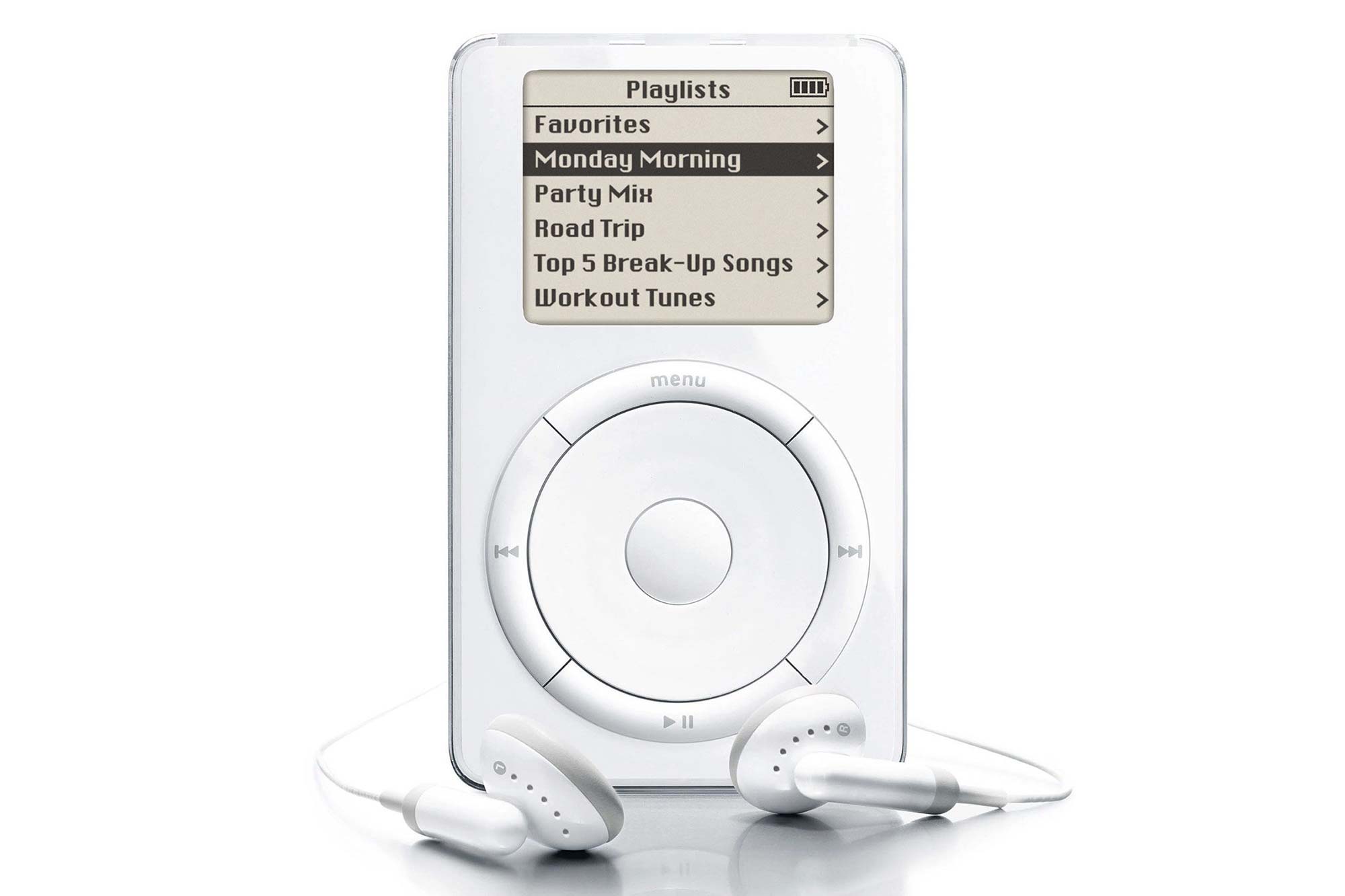

Ok, let’s return to that toddler birthday party. Given that a lot of my design experience is in the EDC (Everyday Carry) space, I tend to explain my work using products we’re all familiar with—items we carry daily. These are things people can instantly pull from their pockets, relate to, and share stories about: your wallet, the watch on your wrist, a pocket knife on your keychain, your eyeglasses, your shoes, or a carabiner holding your keys. The list goes on.

I explain that they bought those items for a reason: either they loved the look of it, or enjoyed the usefulness it presents them, or maybe they carry it because their wife bought it for them and they have to. Regardless, an industrial designer played a crucial role in shaping not only the appearance of those products but also the reasoning behind their creation and functionality.

Let’s take the carabiner that holds my house keys, Swiss Army Knife, and car keys as an example. This product wasn’t created out of thin air. Someone had a pain point or a problem, so they searched for a solution. Maybe they lost their keys frequently, or they disliked removing their Swiss Army Knife Classic SD from those tiny key rings every time they went through TSA at the airport. Perhaps they hated how their keys bulked up their pockets and preferred to carry them outside to save space for other EDC items. Whatever the reason, it always starts with a problem.

Once we define a problem, we map our way to a solution through a chaotic yet organized winding path. The solution we seek needs features and criteria that define its outcome, so we start brainstorming questions: Should it be lightweight? How many keys should it hold? What material should we use? What’s our target price point? How will users interact with it? Is there a market gap for this idea? Are there existing patents that may stop us from innovating?

The questions are endless, and as Industrial Designers, it’s our job to define and solve these questions collaboratively through research, design, prototyping, development, and production. Naturally, reaching a solution in any industry involves compromises. It’s between these compromises and innovations that a great product emerges. Raymond Loewy, a renowned Industrial Designer, coined the perfect term for this fine line: “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable” (MAYA). This concept suggests there’s an ideal time and place for a product’s introduction. Take General Motors’ EV1, the first modern electric car produced in 1996. Despite its innovation, consumers, supply chains, and manufacturers weren’t ready—it wasn’t initially accepted or considered successful. Yet, we need such boundary-pushing products to drive change. Success hinges on addressing the right problem, with the right team, at the right time. EVs eventually went mainstream years later, but only after all the stars aligned.

This same principle and approach applies to any product in our EDC or daily lives. A great product is never created by an Industrial Designer alone—anyone claiming otherwise shouldn’t be trusted!

Success always stems from great collaboration among various parties: researchers who help us understand consumers and opportunities; marketers who uncover the missing edge consumers crave; engineers who bring products to life; graphic designers who make products and experiences shine; operations specialists who coordinate global product movement; manufacturing experts who work wonders with machinery; and shipping companies who deliver products to your doorstep. This is just a glimpse of what it takes to bring that phone you’re using to read this article right to your front door.

During my time as Design Director at The James Brand, we created numerous EDC products, approaching the key carabiner solution in various innovative ways. We often identified standout features that we believed would enhance a product’s functionality, even if they didn’t exist yet. Take the Hardin, for instance—one of The James Brand’s carry solutions. We ensured the keys were securely housed in their own compartment at the bottom, with an L-shaped gate separate from the attachment point. The carabiner’s top was designed to be smooth, making it easy to clip onto jeans or a bag. We opted to hot-forge it from 6063 aluminum, ensuring it was lightweight and unobtrusive when carried. Each of these elements was meticulously considered, sketched, designed, prototyped, and developed to perfectly suit the consumer’s needs.

A simple product often belies the complexity of its creation. This meticulous process and attention to detail are hallmarks of most great products we use daily. Our aim is to continually improve products and experiences without sacrificing what we cherish about their predecessors. After all, we are standing on the shoulders of giants, and sometimes, rather than reinventing the wheel, maybe a slightly better wheel will do just fine.

But let’s be real, and not take ourselves too seriously. As my friend James (a very successful designer himself) says, when that Hollywood asteroid actually hurls itself towards Earth on doomsday, the United Nations isn’t going to immediately convene to decide which Industrial Designer will save humanity. They’ll convene to assemble the best group of people to collaborate and save our souls.

You never know, though…they might call up Marc Newson, Konstantin Grcic, Naoto Fukasawa, Patricia Urquiola, or even Jony Ive to join that team!

Note from the Author: For the best all around information on what Industrial Design is in more detail, I highly recommend watching ‘Objectified’ written and directed by Gary Hustwit.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos