As the ‘60s drew to a close and gave way to the early 1970s, the traditional Swiss industry was erupting into full-blown crisis. While the waking giant of Seiko might have set the old players off balance, the advent of affordable quartz watches threatened to shake the whole system to the ground. The old observatory trials at Neuchatel and Geneva, once vital not just to industry pride but to accurate navigation as well, suddenly seemed quaint and obsolete. If the finest mechanical movement, slaved over for years by master watchmakers, could be humiliated by a simple battery-powered piece, what was the point?

continued from part 1 and part 2.

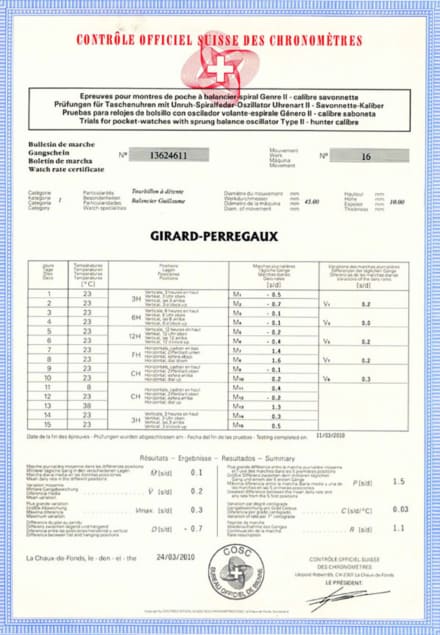

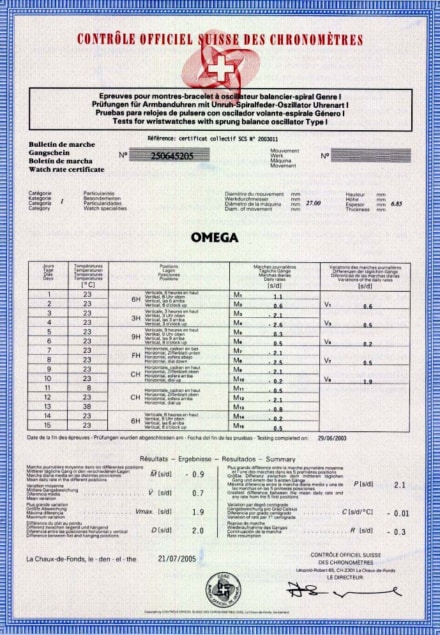

The death of the observatory trials left a major power vacuum, however. In the early ‘70s, quartz technology was still in its infancy, and the vast majority of consumer watches were still mechanically powered. The buying public was still hungry for accurate movements, but without a regulating body there was little consensus on what “accurate” really meant. To bring order and to re-establish a chronometer standard, representatives from the Swiss observatories, the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, and the five watchmaking cantons of Bern, Geneva, Neuchatel, Solothurn, and Vaud joined forces in 1973 to create a new non-profit organization. This organization, the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres or COSC, had a singular purpose—create a standard and certify Swiss chronometer movements.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos