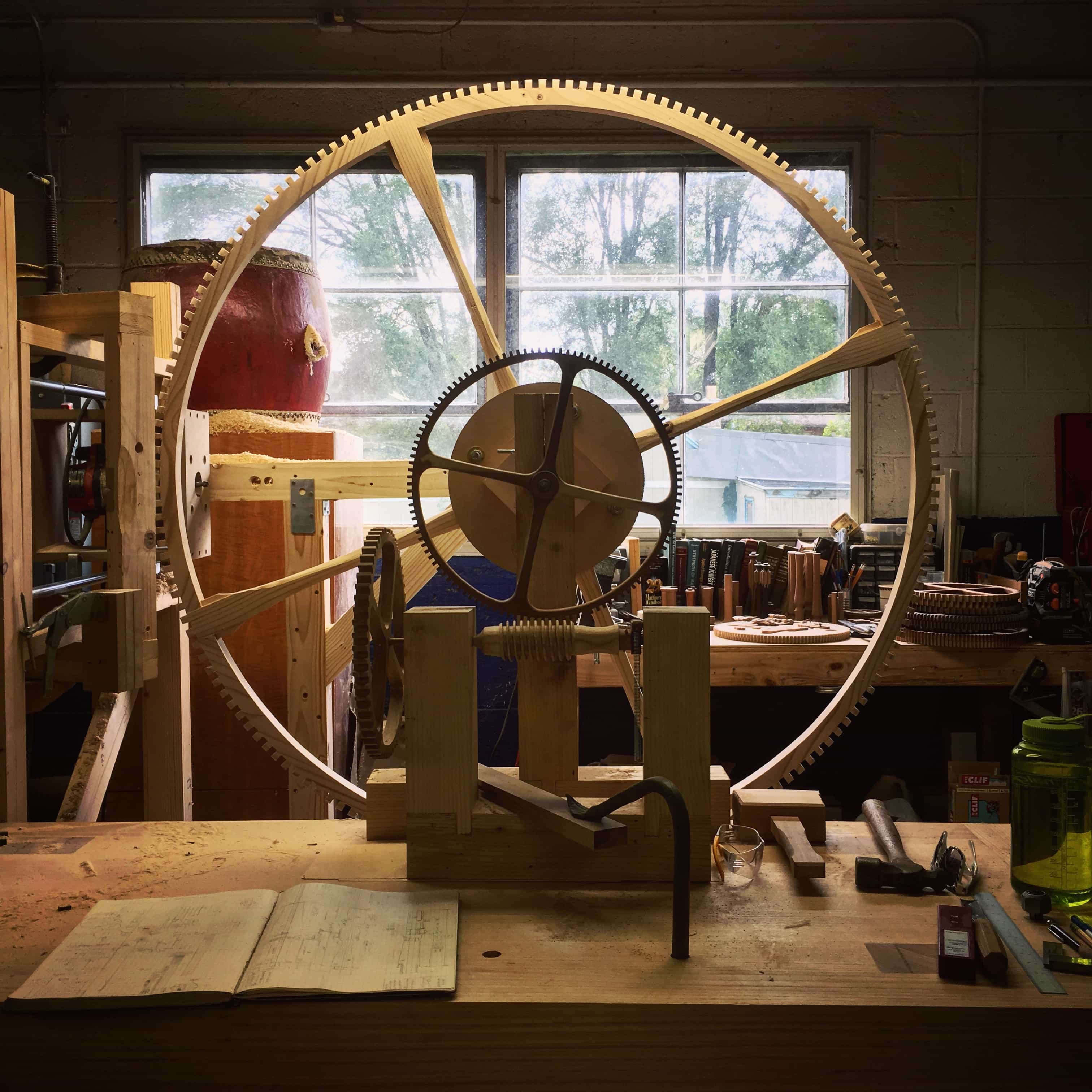

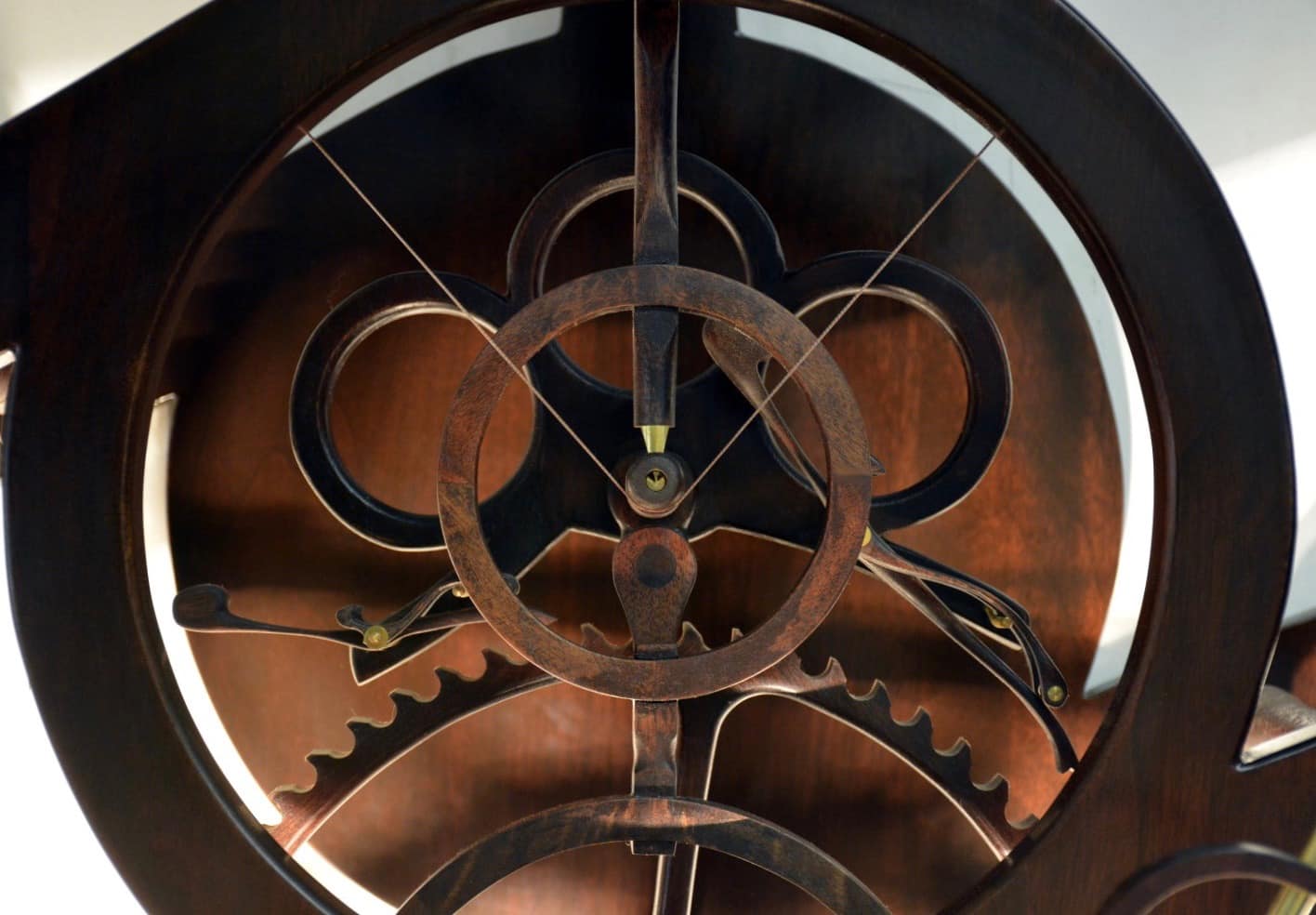

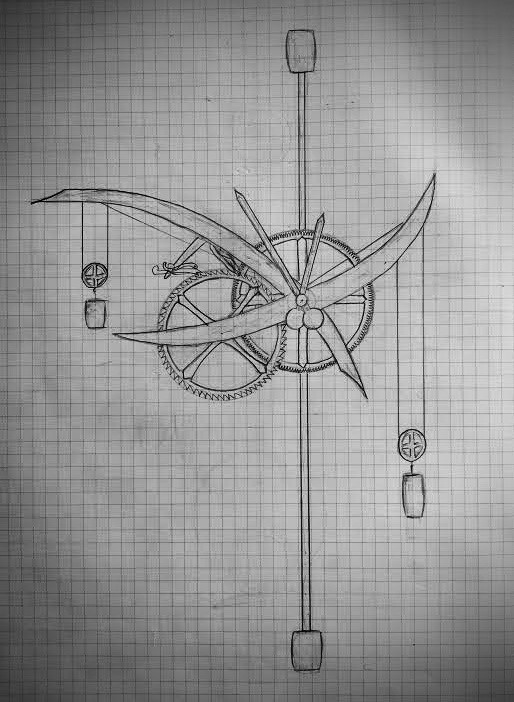

Inside a woodworking studio in Michigan, 27-year-old Rick Hale is working on another handmade clock. He carefully shaves away layers of wood. He takes his time. One slip of the wrist or a dig too deep with a chisel can ruin a clock. He has to be completely focused. And he has to stay focused like this for up to 800 hours over several months in order to complete his latest work of horological art.

Hale said that while working long hours on a piece, he can get into a “flow state.” He’s neither happy nor sad. He’s not concentrating too hard, and he’s not completely relaxed.

“You’re not feeling any emotion, necessarily. You’re 100 percent in the moment,” Hale says. “Whether you know it cognitively or not, you’re doing exactly what you’re supposed to be doing at that moment. That’s what I strive for.”

Featured Videos

Featured Videos