Watches can be, well, complicated, and not all of the information out there is always accurate or reliable. So we’ve brought onboard Ashton Tracy, a seasoned watchmaker, to kick off a new series we’re calling Watchmaker’s Bench to explore some common questions, misconceptions, and ideas about watches. Today, we’re looking at integrated versus modular chronographs, but if there is something else you want Ashton to delve into, then send us your inquiry to [email protected] and we will consider it for the next installment.

As a watchmaker, I’ve seen it all—the good, the bad, and the ugly—when it comes to chronographs. One of the questions I often see asked is, are all chronographs created equal, and more specifically, what is the difference between an integrated chronograph and a modular one? That’ll be the primary focus of today’s article.

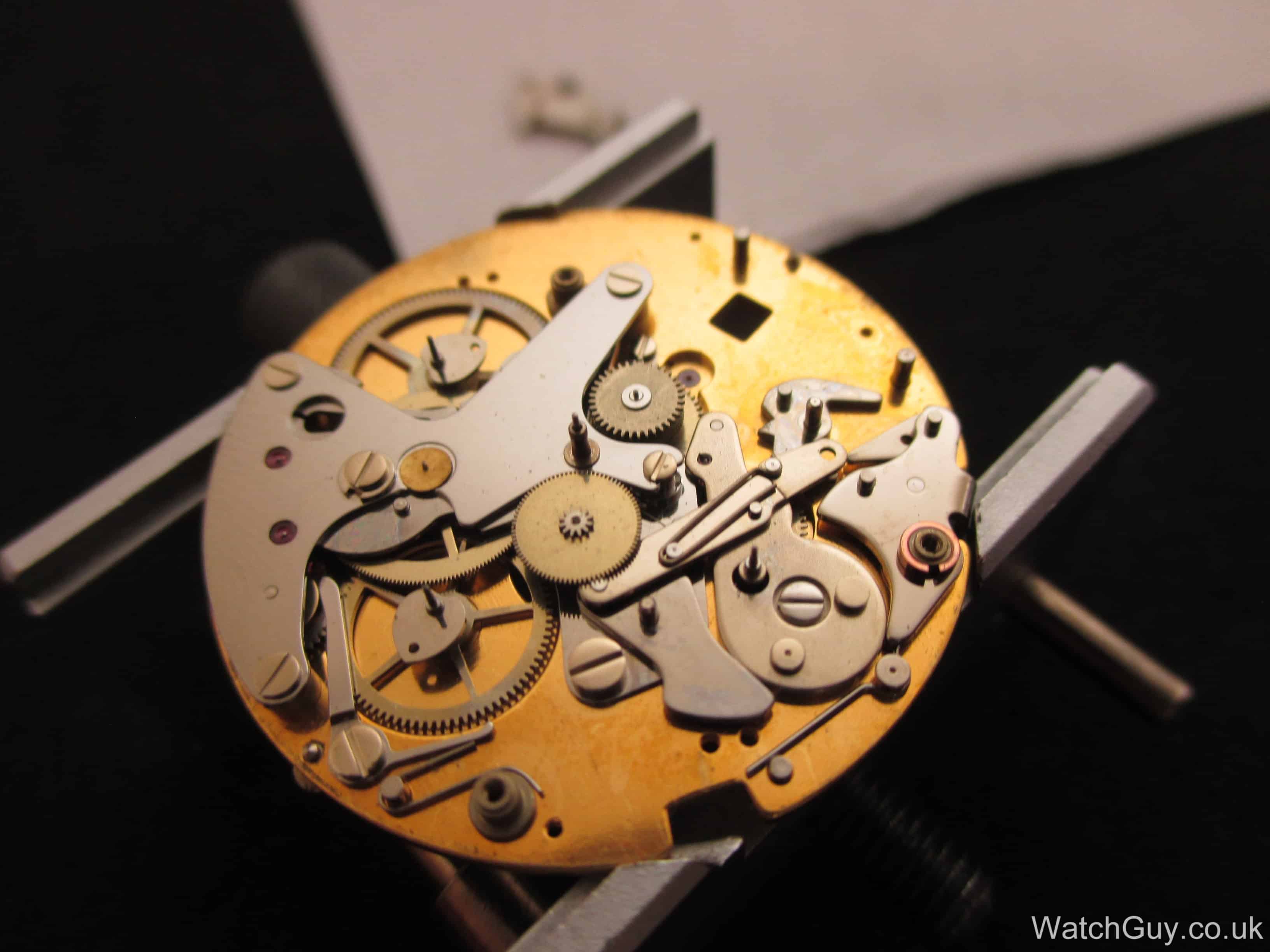

Over the last couple of decades, there have been two main types of chronographs: the integrated chronograph and the modular chronograph. An integrated chronograph is basically what it sounds like—the chronograph complication is built into the base movement and the two are designed to work together.

A modular chronograph is an entirely different beast. The chronograph complication on this type of movement is an independent unit that is attached to a previously existing base caliber. For example, a module can be attached to an ETA 2892, transforming it into a chronograph. It’s quite a clever idea, and I’m not the only one who thinks so. Modular systems have been used by Omega, Breitling, Audemars Piguet and even Richard Mille, just to name a few. But is one better than the other? Let’s examine more closely.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos