The keyless works get its name from the fact that one does not need a key to wind or set a watch. Before the introduction of the keyless works, however, this was exactly how it was done. As we all know, the vast majority of watches today are wound and set via the crown/winding stem, and when we wind the watch or pull the crown out to set the time, we are engaging the keyless works.

In the final part of our series, What Makes It Tick?, we will look at each aspect of the keyless works and the hand setting mechanism in detail. For Part 1 of our series, which focused on the wheel train, click here, and for Part 2, which focused on the escapement, click here.

Winding Mechanism – Stem, Winding, and Sliding Pinion

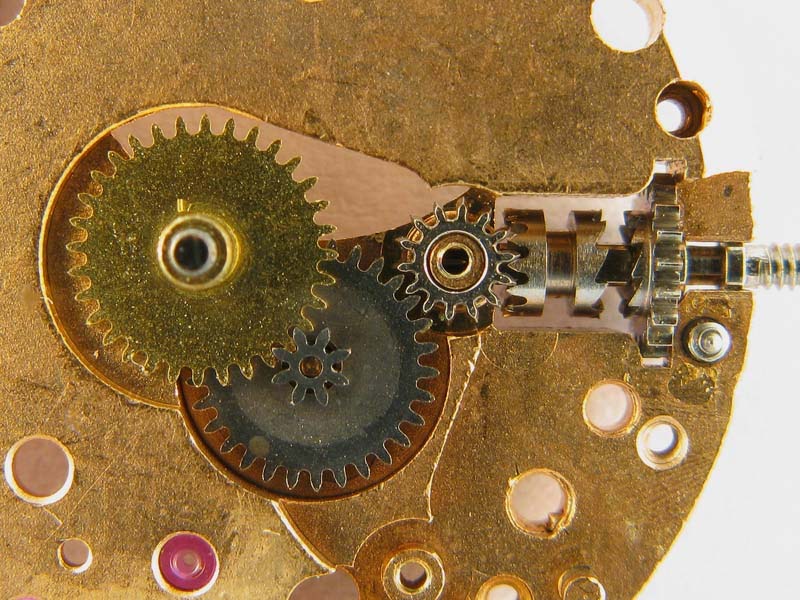

The crown of a watch is connected to what’s known as a winding stem. This is a shaft that the crown threads into, and it’s the interface between the inside and the outside of a watch. The winding stem is made up of many different surfaces, all integral to its many functional purposes. We have clylindrical pivots, a square section, cut outs for posts to engage, and a threaded section for where the crown attaches.

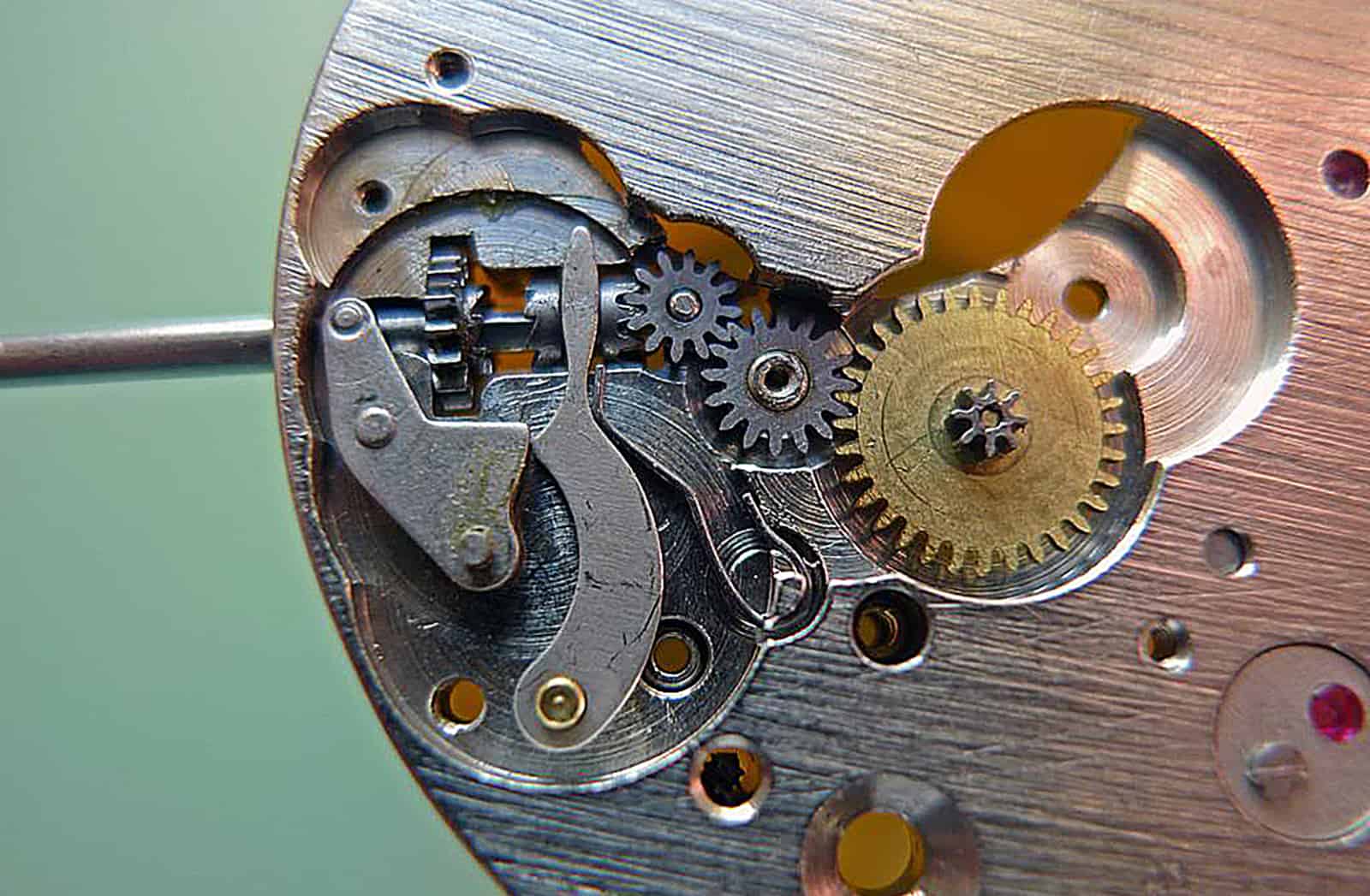

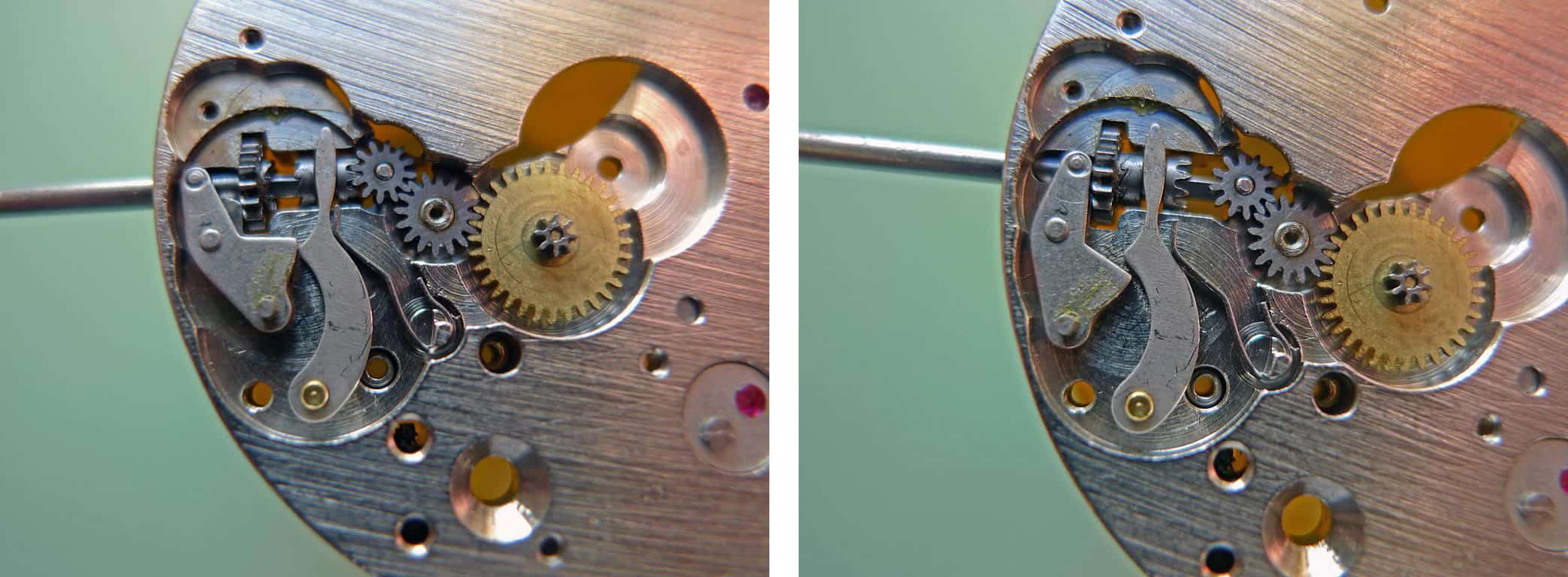

Next, let us look at the winding pinion and sliding pinion. The winding and sliding pinions slide on to the winding stem. These two small wheels engage each other to ensure that the mainspring can be wound. The winding pinion is seated on a cylindrical section of the winding stem, and the sliding pinion is seated on the square. The winding pinion can rotate freely but the sliding pinion is fixed. The two pinions engage each other via teeth that act as a clutch. When the crown is wound anti-clockwise, the winding pinion can spin freely, and it does not engage any gears. But when it is wound clockwise, the sliding pinion engages with the teeth of the winding pinion so that it can then interact with the wheels that wind the mainspring.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos