The attraction of the vintage tool watch for many is that these were timepieces built to do a specific job as accurately as possible, and, as such, form almost always followed its utilitarian function. Military wristwatches, of course, often took this idea to the extreme, with nothing extraneous added, and nothing essential left out of the design.

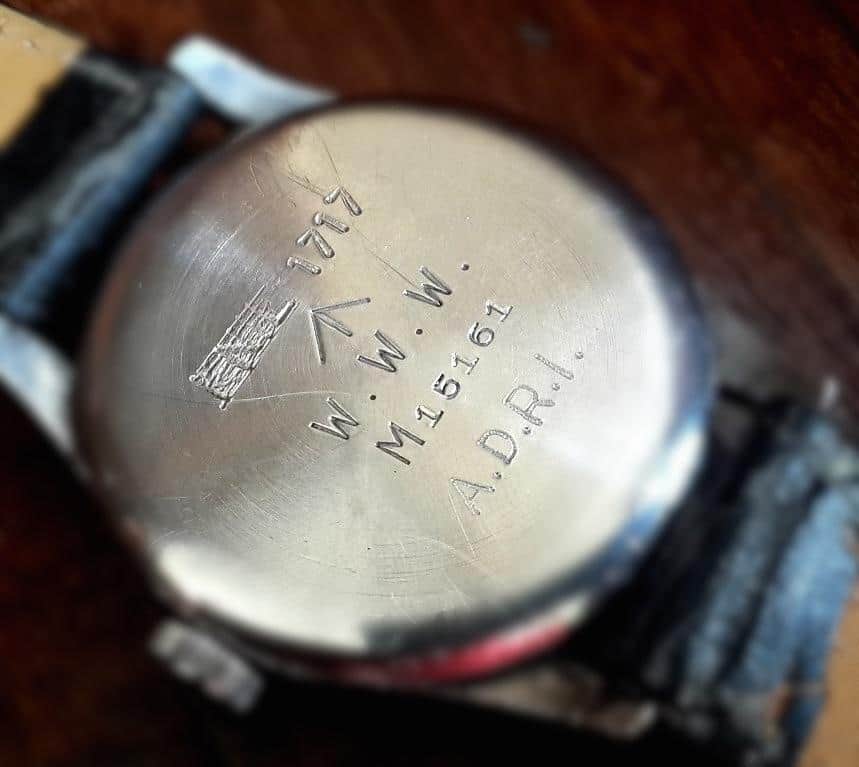

During World War II, the British imported Swiss wristwatches and issued them under the A.T.P. moniker (Army Trade Pattern); most of these were 29–33-millimeter chrome or steel-cased watches with white or silver dials, luminous pips or baton indices, running central or sub-seconds, and 15-jewel movements with snap or screw back cases. However, the MoD eventually decided that these watches, which were essentially civilian models with military dials and spec/issue numbers, weren’t cutting it in the field, and they drew up a specification for a new wristwatch designed to fit the particular needs of Her Majesty’s Government—an ideal military watch where, yes, form followed function.

The new spec resulted in the W.W.W., the acronym for Wrist, Watch, Waterproof, but the watches themselves have become known colloquially as “The Dirty Dozen,” both as a reference to the famous 1967 war film, and because the timepieces were produced by a total of 12 Swiss firms. Because the watches weren’t delivered until between May and December of 1945, it is unlikely that any saw any wartime use in Europe during WWII (V-E Day was May 8, 1945), but the watches remained in circulation for some years afterward, and, as you will read below, some were even reissued to other militaries.

Because the 12 contracted firms each differed in size and production capabilities, each company simply delivered as many watches as it was capable of producing, with roughly 150,000 watches delivered in total.

Featured Videos

Featured Videos